Recently, I spent some time in Latin America, first in the “Tango” country, Argentina, attending the International Federation of Infection Control (IFIC) 2013 conference and then in Panama giving a talk at a symposium. Talking to doctors and other healthcare workers from across Latin America during these two events, it was clear that multidrug resistance, especially carbapenemase and ESBL production in Enterobacteriaceae and other Gram-negative bacteria, are major problems in the region.

This prompted me to review the status of carbapenem resistance among the major nosocomial Gram-negatives in Latin America and ESBL production in E. coli and Klebsiella. Unlike the US and Europe, data on antimicrobial resistance from Latin American countries is limited. Some Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Chile and Colombia, do possess a nationwide surveillance program for monitoring antimicrobial resistance. However, the data are rarely in the public domain. Other countries such as Brazil and Mexico don’t yet have such monitoring programs. This makes it difficult to estimate the accurate prevalence and burden of diseases caused by antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in this part of the world.

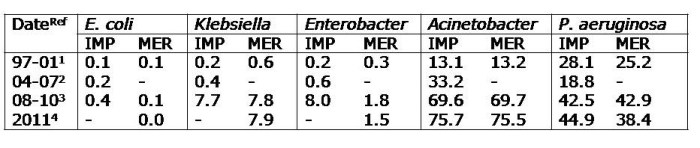

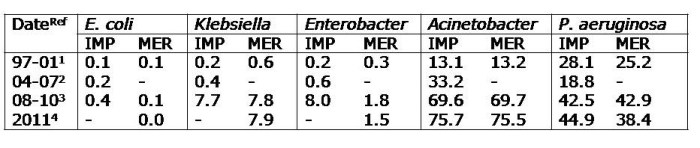

Thankfully, some data are flittering through from several national and international reports, including the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (Table). SENTRY has been monitoring the predominant pathogens and antimicrobial resistance patterns of nosocomial and community-acquired infections via a broad network of sentinel hospitals since 1997 using validated, reference-quality identification and susceptibility testing methods performed in a central laboratory. Data from the SENTRY reports identify the five most frequently isolated Gram-negatives in Latin America as the Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterobacter), P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter.3

Table. Percentage of carbapenem resistance among the main nosocomial Gram-negatives in Latin America. IMP; imipenem, MER; meropenem

IMP; imipenem, MER; meropenem

Resistance of these organisms to carbapenems has been increasing over the years, especially among Klebsiella, P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter. The 1997-2001 SENTRY program reported on the antimicrobial resistance of 8,297 isolates of the 5 above organisms for 7 Latin American countries (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Uruguay and Venezuela).1 The data found carbapenems to be effective against Enterobacteriaceae (<1% resistance level). Resistance among Acinetobacter and P. aeruginosa was around 13% and 26% respectively. In 2001, carbapenem resistance among the Enterobacteriaceae remained <1%, while resistance for Acinetobacter and P. aeruginosa rose to around 17% and 36% respectively.

The Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (TEST)2 reported the antimicrobial resistance of bacteria from 33 centres in Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico and Venezuela) between 2004 and 2007, finding that imipenem-resistance among Enterobacteriaceae remained stable at <1%. However, resistance of Acinetobacter to imipenem increased to 33.2%.

The 2008-2010 SENTRY report from 10 Latin American medical centres located in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico, found a marked increase in imipenem and meropenem resistance among Klebsiella (7.7% and 7.8% respectively) and Enterobacter (8% and 1.8% respectively).3 KPC-2 was prevalent in Klebsiella but OXA-163, IMP and VIM were also detected. There was an important increase in KPC-2 producing K. pneumonia noted in Argentina and Brazil. Colistin resistance was highest among Klebsiella and Enterobacter with resistance rates of 3.1% and 17.6%, respectively. Nearly 70% of Acinetobacter were resistant to carbapenems and 1.2% were resistant to colistin. There was a marked increase in resistance in this organism particularly in Argentina and Brazil. OXA-23 and OXA-24were the most frequent OXA-carbapenemase genes detected. In P. aeruginosa, 42% of the isolates were resistant to carbapenems and 0.3% were resistant to colistin.

A recent article reported the antimicrobial resistance among 3,040 Gram negatives collected in 2011 from 11 countries in Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Peru and Venezuela).4 With the exception of Mexico (1.1%), all other countries had high rates of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) (10-20%). Panama, Colombia and Brazil had particularly high rates of 20%, 18.2% and 17.3% respectively. Resistance in Enterobacter was 2.9% with the highest rates in Colombia and Venezuela (10-12.5%). KPC-2 was identified in Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela, KPC-3 in Colombia and Panama while NDM-1 was also found in Colombia.

ESBL production by E. coli and Klebsiella isolated from Latin America is a well-recognized problem. The prevalence of ESBL-producers in Latin America has progressively increased over the years (Figure). The rates of these isolates in the region are now in excess of 50% in some regions.4 Peru, Guatemala and Chile have the highest ESBL-producing Klebsiella rates (70%, 69% and 59% respectively), while Mexico, Guatemala and Peru have the highest rates of ESBL-producing E. coli (71%, 59% and 54% respectively).

Figure. Inexorable rise in rate of of ESBL-producing E. coli and Klebsiella in Latin America.

Figure. Inexorable rise in rate of of ESBL-producing E. coli and Klebsiella in Latin America.

It is clear that increasing antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negatives is a major problem in Latin America. The spread of carbapenem resistance is particularly troubling with increase prevalence of KPC and NDM carriage. Steps to reduce the transmission of these pathogens in Latin America require strategies at the institutional, community, national and international levels. For a start, it is important that true the prevalence rate of antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negatives in Latin America is determined at national levels with robust surveillance systems. Effective antibiotic stewardship and the control of inappropriate antibiotic use are important to slow the proliferation of resistant strains and should be targeted at both hospital and community levels. Strict infection control measures and targeted screening and isolation of patients with problematic strains should also help to slow the spread of resistant Gram-negatives in Latin America.

References

- Sader HS, Jones RN, Gales AC et al. SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program report: Latin American and Brazilian results for 1997 through 200. Braz J Infect Dis 2004;8:25-79.

- Rossi F, García P, Ronzon B et al. Rates of antimicrobial resistance in Latin America (2004-2007) and in vitro activity of the glycylcycline tigecycline and of other antibiotics. Braz J Infect Dis 2008;12:405-15.

- Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS. Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008-2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;73:354-60.

- Jones RN, Guzman-Blanco M, Gales AC et al. Susceptibility rates in Latin American nations: report from a regional resistance surveillance program (2011). Braz J Infect Dis 2013 Oct 10.

- Paterson DL, Rossi F, Baquero F et al. In vitro susceptibilities of aerobic and facultative Gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients with intra-abdominal infections worldwide: the 2003 Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART). J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;55:965-73.

- Rossi F, Baquero F, Hsueh PR et al. In vitro susceptibilities of aerobic and facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients with intra-abdominal infections worldwide: 2004 results from SMART (Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends). J Antimicrob Chemother 2006;58:205-10.