If, in 2004, I’d told an MRSA expert that there would be around only 200 MRSA bloodstream infections (BSI) per quarter in England throughout 2014 they’d have laughed out loud. This is because, back in 2004, there were sometimes more than 100 MRSA BSI per month in some London hospitals (and around 2000 per quarter nationally), combined with a general perception that only around 30% of MRSA BSI are preventable. How wrong we were.

The reduction of MRSA BSI in England has been dramatic, with a reduction in the region of 90% achieved over a 5 year period. I was asked to speak on “The English MRSA Miracle” at a conference in Portugal today, so thought I’d share my thoughts. You can download my slides here.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly what is behind the ‘MRSA Miracle’ since quite a number of interventions occurred at more or less the same time (Figure 1):

Figure 1: National interventions aimed at reducing MRSA BSI.

Some have postulated that the national cleanyourhands campaign is responsible for the dramatic success. Indeed, there is a BMJ study that makes this case, showing that the national significant increase in the use of soap and water and alcohol gel correlated with the reduction in MRSA BSI. However, I contend that this can’t be the case because what has happened to the rate of MSSA and E. coli BSI over the same period? Nothing – no reduction whatsoever. If increases in hand hygiene compliance really do explain the reduction in MRSA BSI, then they should also reduce the rate of MSSA BSI (unless the increase in hand hygiene compliance only occurred after caring for MRSA patients, which seems unlikely).

There’s a more important epidemiological point here though. High-school tells us to change one variable at a time in science experiments. And yet in this case multiple variables were modified, so it’s not good science to try to pin the reduction to a single intervention, no matter how strong the correlation. (I should add that the authors of the BMJ study do qualify their findings to a degree: ‘National interventions for infection control undertaken in the context of a high profile political drive can reduce selected healthcare associated infections.’)

There has been much discussion about whether we should be investing in a universal or targeted approach to infection control. The failure of improved hand hygiene to make any impact on MSSA BSI suggests that targeted interventions are behind the reduction in MRSA. So what targeted interventions were implemented that may have contributed to the decline? MRSA reduction targets were introduced in 2004, a series of ‘high-impact interventions’ focused mainly on good line care in 2006 and revised national guidelines in 2006 (including targeted screening, isolation and decolonization) all contributed to a surge of interested infection control. Infection control teams doubled in size. Infection control training became part of mandatory induction programmes. And hospital chief executives began personally telephoning infection control to check “how many MRSA BSIs” they had left.

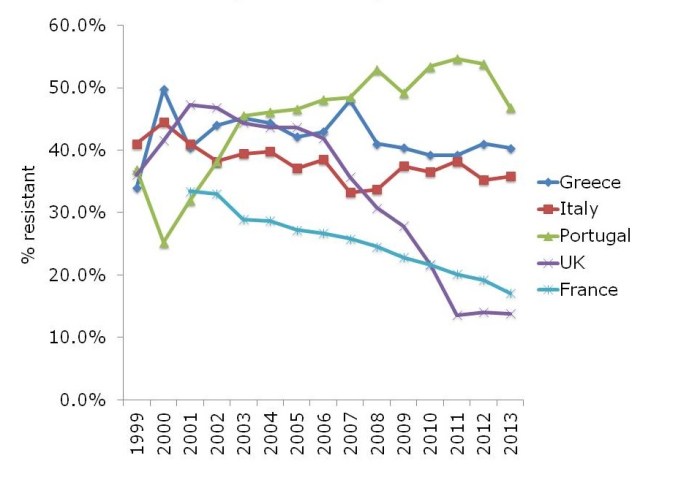

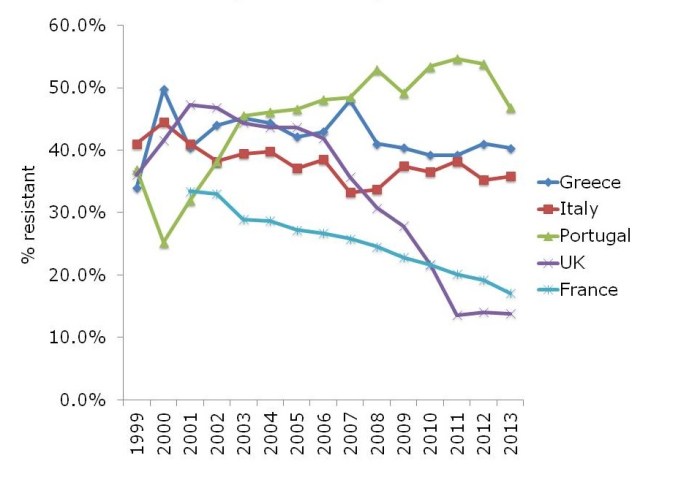

The ‘English MRSA Miracle’ has not been matched in most parts of Europe, except in France, which has had a rather more steady ‘MRSA Miracle’ of its own (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rate of methicillin-resistance in invasive S. aureus infections, from EARS-Net.

What is behind the failure of most European countries in controlling MRSA? The barriers are multifactorial, but include high levels of antibiotic use, a lack of single rooms for isolating patients, infection control staffing, and, of course, crippling national debt (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Barriers to infection prevention and control in Europe.

If the English MRSA Miracle is to be replicated across Europe, it will take concerted national initiatives to raise the profile of infection control, combined with considerable investment, which is challenging in these times of austerity.