We have precious little data on what works to prevent the transmission of MDR-GNR. An interesting article published recently in CID provides invaluable data that an infection control programme aimed at reducing MRSA (and succeeding) was also effective in reducing GNR BSI!

universal

Should we throw out the chlorhexidine with the bathwater?

Following hot on the heels of a series of studies showing that daily bathing using chlorhexidine reduces the risk of HCAI, a recent study suggests that chlorhexidine daily bathing does not reduce HCAI. The headline finding is that chlorhexidine bathing did not reduce HCAI. Before throwing out the chlorhexidine with the bathwater, it’s worth considering the limitations of the study.

The English MRSA Miracle

If, in 2004, I’d told an MRSA expert that there would be around only 200 MRSA bloodstream infections (BSI) per quarter in England throughout 2014 they’d have laughed out loud. This is because, back in 2004, there were sometimes more than 100 MRSA BSI per month in some London hospitals (and around 2000 per quarter nationally), combined with a general perception that only around 30% of MRSA BSI are preventable. How wrong we were.

The reduction of MRSA BSI in England has been dramatic, with a reduction in the region of 90% achieved over a 5 year period. I was asked to speak on “The English MRSA Miracle” at a conference in Portugal today, so thought I’d share my thoughts. You can download my slides here.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly what is behind the ‘MRSA Miracle’ since quite a number of interventions occurred at more or less the same time (Figure 1):

Figure 1: National interventions aimed at reducing MRSA BSI.

Some have postulated that the national cleanyourhands campaign is responsible for the dramatic success. Indeed, there is a BMJ study that makes this case, showing that the national significant increase in the use of soap and water and alcohol gel correlated with the reduction in MRSA BSI. However, I contend that this can’t be the case because what has happened to the rate of MSSA and E. coli BSI over the same period? Nothing – no reduction whatsoever. If increases in hand hygiene compliance really do explain the reduction in MRSA BSI, then they should also reduce the rate of MSSA BSI (unless the increase in hand hygiene compliance only occurred after caring for MRSA patients, which seems unlikely).

There’s a more important epidemiological point here though. High-school tells us to change one variable at a time in science experiments. And yet in this case multiple variables were modified, so it’s not good science to try to pin the reduction to a single intervention, no matter how strong the correlation. (I should add that the authors of the BMJ study do qualify their findings to a degree: ‘National interventions for infection control undertaken in the context of a high profile political drive can reduce selected healthcare associated infections.’)

There has been much discussion about whether we should be investing in a universal or targeted approach to infection control. The failure of improved hand hygiene to make any impact on MSSA BSI suggests that targeted interventions are behind the reduction in MRSA. So what targeted interventions were implemented that may have contributed to the decline? MRSA reduction targets were introduced in 2004, a series of ‘high-impact interventions’ focused mainly on good line care in 2006 and revised national guidelines in 2006 (including targeted screening, isolation and decolonization) all contributed to a surge of interested infection control. Infection control teams doubled in size. Infection control training became part of mandatory induction programmes. And hospital chief executives began personally telephoning infection control to check “how many MRSA BSIs” they had left.

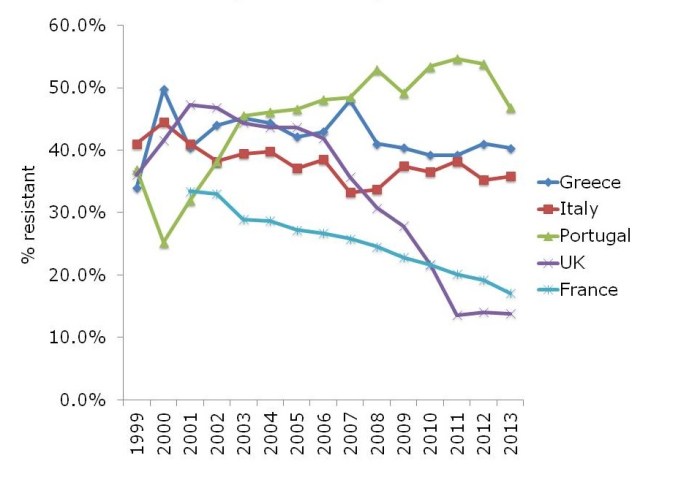

The ‘English MRSA Miracle’ has not been matched in most parts of Europe, except in France, which has had a rather more steady ‘MRSA Miracle’ of its own (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rate of methicillin-resistance in invasive S. aureus infections, from EARS-Net.

What is behind the failure of most European countries in controlling MRSA? The barriers are multifactorial, but include high levels of antibiotic use, a lack of single rooms for isolating patients, infection control staffing, and, of course, crippling national debt (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Barriers to infection prevention and control in Europe.

If the English MRSA Miracle is to be replicated across Europe, it will take concerted national initiatives to raise the profile of infection control, combined with considerable investment, which is challenging in these times of austerity.

Preventing HCAI: go long or go wide?

There seems to be a general movement away from targeted, pathogen-based precautions (principally screening and isolation) in the USA. This changing professional opinion was clear from the recent SHEA conference, where several leading experts gave what amounted to a collective justification for abandoning contact precautions for MRSA.

There seems to be a general movement away from targeted, pathogen-based precautions (principally screening and isolation) in the USA. This changing professional opinion was clear from the recent SHEA conference, where several leading experts gave what amounted to a collective justification for abandoning contact precautions for MRSA.

The update of the SHEA Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals is accompanied by a commentary from a group of leading US figures titled ‘Approaches for preventing HCAI: Go long or go wide’. In the commentary, the authors weigh the evidence and opinion for so-called ‘vertical’ (aka targeted) vs. ‘horizontal’ (aka universal) interventions (Table).

Table: Go long or go wide? Examples of targeted and universal interventions (adapted from Wenzel & Edmond, via Septimus et al.).

Table: Go long or go wide? Examples of targeted and universal interventions (adapted from Wenzel & Edmond, via Septimus et al.).

The commentary outlines the potential drawbacks of targeted approaches (such as fewer visits from healthcare workers and feelings of isolation), but doesn’t spend a lot of time discussing the potential drawbacks of universal approaches. For example, “isolation fatigue”, where a procedure loses its impact if it has to be applied to every patient. And then there’s the possibility of resistance when performing universal decolonization. This is particularly worrysome when using antibiotics, but could also be a problem when using biocides such as chlorhexidine.

I’m not ready to abandon pathogen-based targeted interventions just yet. Conceptually, it just does not make sense. If you have a patient with MRSA and a respiratory virus, chances are they will become a ‘super-spreader’. Those who favour universal approaches do make some provision for exceptional cases that really should be identified and isolated via a ‘syndromic’ approach to isolation: crudely, only isolate patients when they’re oozing. However, this syndromic approach would likely miss our ‘super-spreading’ patient, which may well result in an MRSA outbreak – that we could all do without.

Furthermore, if you have a patient who is colonized with CRE, are you brave enough to take no special precautions, as would be the case for a ‘universal only’ approach? The success of this strategy would depend on a high level of compliance with standard precautions such as hand hygiene and environmental cleaning and disinfection. Whilst sound in theory, this just doesn’t happen in the trenches; your facility is above average if your hand hygiene compliance rate is the right side of 40%. Whilst still not 100%, hand hygiene compliance is higher when patients are placed in isolation, most likely because there’s a stronger psychological trigger to comply with hand hygiene.

It’s important to note that targeted and universal approaches are by no means mutually exclusive. For example, on our ICU in London, we have been using universal chlorhexidine decolonization for a decade combined with targeted screening and isolation, and have seen a dramatic reduction in the spread of MRSA.

So, should we go long or go wide in the prevention of HCAI? The answer is both. We should optimize case for all patients, which means careful standard precations with liberal application of chlorhexidine and tight restriction of antibiotics. But we should also identify those with communicable pathogens and segregate them from others. In this regard, we have the weight of history on our side.

Image: Jeff Weese.

Could universal glove use provide a false sense of security?

Hand Hygiene and Self-Protection

Hand Hygiene and Self-Protection

Guest blogger Carolyn Dawson (bio below) writes: The BUGG study provides support for the concept of self-protection in hand hygiene through its findings that healthcare professionals were more likely to perform hand hygiene after leaving a patient room than upon entry (mean compliance at room exit vs. entry in intervention universal glove and gown group: 78.3% vs. 56.1%, respectively; mean compliance control group: 50.2% vs. 62.9%, respectively). This may suggest a stronger awareness of contamination occurring on the hands during patient interaction than of contamination having occurred prior to patient contact. It may also indicate a higher prioritisation of the implications of contamination acquired during, rather than prior to, patient contact.

The discussion here is how such self-protection themes may affect the concept of universal glove use providing a benefit to patient safety. The “urgh” factor provides a simple phrase to represent instinctive hand hygiene drivers, both at times when hands become physically soiled and when they are in contact with things which have an “emotionally dirty” association (e.g. armpits, clean bedpans) (based on Whitby et al., 2006). The “urgh” factor has been shown to increase likelihood of hand hygiene occurring in clinical practice (my research).

The “urgh” factor can be useful for driving hand hygiene: despite other pressing variables, such as time and workload, this instinctive self-protective driver increases the likelihood that hand hygiene will still occur on some occasions, providing the related patient and healthcare professional safety benefits. But it also means that there is less of a psychological driver for hand hygiene following contact with things that are perceived as “clean” but may be as contaminated as perceived “dirty” items.

Glove use reduces the “urgh” factor

The use of gloves (including inappropriate/over-use) has been shown to be driven by themes including disgust and fear (e.g. Wilson et al, 2013), suggesting their use leads to a feeling of security, reducing this “urgh” factor. Therefore, one could expect that activities previously resulting in high levels of hand hygiene would be affected by the adoption of universal glove use, as the “urgh” factor influence is reduced. In other words, if you are wearing gloves, you are less likely to feel repulsed by touching something you previously would have, and thus, in turn, are less likely to perform hand hygiene. Glove use is no substitute for effective hand hygiene, which should be performed both before and after gloves are used, and at specific points during patient care (RCN 2012).

For example: imagine moving from changing a catheter bag, to cleaning a wound. Both hand hygiene and the changing of gloves must be performed. With respect to the “urgh” factor, one could expect that instinctive drivers would motivate hand hygiene in this example, as self-protective drivers lean towards decontamination after handling the catheter bag. However, when gloves are used these desires may be muted, leaving a stronger demand on the knowledge and skills of the healthcare professional to perform necessary hand hygiene and glove use protocol.

‘Correct’ and ‘Incorrect’ glove use

It is worth noting that the definition of ‘appropriate’ use of gloves is subjective, with different settings likely to adhere to different standards and guidelines. Thus, caution is required when discussing ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ use of gloves. There are, however, some less debatable examples where gloves are not recommended due to low risk of contamination (RCN 2012, Appendix 1), yet gloves are often used e.g. collecting equipment, writing notes (Flores and Pevalin, 2006).

The use of gloves for these activities combined with uninterrupted use of gloves (from one activity/area to another without removal – Girou et al., 2004), likely results in microbial cross-contamination via the surface of these gloves. Such activities provide no “urgh” factor safety net, therefore the need to change gloves and perform required hand hygiene requires conscious decisions from the healthcare professional, demanding cognitive input. Commenting on the misuse of gloves, Fuller et al. (2011) wrote: “the reality is that healthcare workers do not always clean their hands before donning gloves, that their hands pick up further organisms during high-risk contacts, and that hands are not always cleaned when the gloves are removed.” It seems likely that a move towards universal gloving would result in more inappropriate ‘continued use’ activities occurring.

Correct, not universal glove use

Such knowledge suggests that rather than looking towards universal gloving as a preventative strategy, continued focus should be turned towards ensuring current glove use is appropriate, seeking to harness the “urgh” factor safety net to drive hand hygiene compliance.

Carolyn Dawson Bio

I am about to submit a PhD dissertation on healthcare hand hygiene which explores the challenges faced in monitoring, measuring and providing feedback compliance data: the audit process. My research questions the potential of hand hygiene technologies (electronic surveillance) as an aid for this process, insisting that first their ‘Fitness-For-Purpose’ must be evaluated using recognised standards. The application of behavioural theory to understand how different activities may influence whether hand hygiene is executed is explored through pilot work on ‘Inherent’ and ‘Elective’ hand hygiene. This case study research has been carried out within an NHS acute setting, however application of the WHO “My 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene” as a core element allows the potential for future work to build upon this foundation outside the current setting. Prior to beginning my PhD I graduated with a BSc in Psychology and an MA from Warwick Business School, and then spent 6 years working for a global laser company as a Project Analyst.

Photo credit: CDC / Amanda Mills.

This study has been BUGGing me for a while

A fabulous study recently published in JAMA evaluates the ‘Benefits of Universal Glove and Gown’ (BUGG) in US ICUs. This is a model study design: one of the first cluster randomized controlled trials of a non-therapeutic infection control intervention. Twenty ICUs were paired and randomized to either universal glove and gowning, or to continue the current practice of placing patients known to be infected or colonized with MRSA and VRE on contact precautions. The hypothesis is that undetected colonization with MRSA and VRE is common, and the only real way to address this is to assume everybody is colonized!

Summary of findings:

- Universal glove and gowning was not associated with a reduction in a composite measure of MRSA / VRE acquisition (the primary outcome).

- VRE acquisition was not reduced by universal glove and gown use, whereas MRSA was.

- CLABSI, CAUTI and VAP; ICU mortality; and adverse events did differ significantly between the two groups.

- Hand hygiene compliance on room entry was not significantly different between the two arms, whereas hand hygiene compliance on room exit was significantly higher in the intervention arm.

- Healthcare workers visited patients 20% less frequently in the intervention arm (4.2 vs. 5.2 visits per hour).

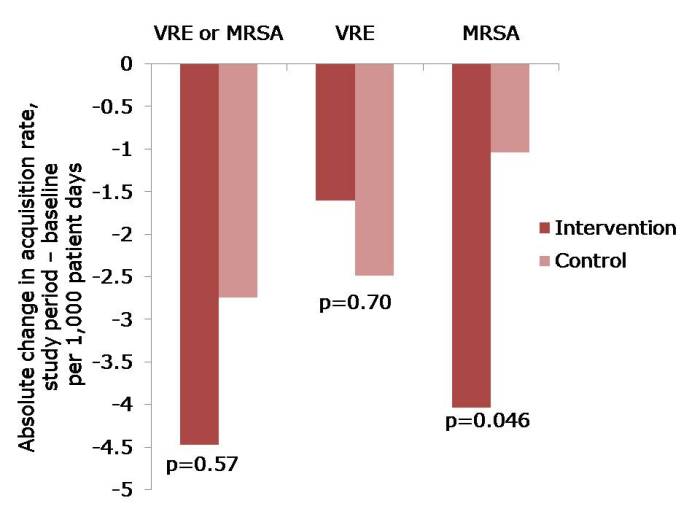

Figure: The change in acquisition rate, comparing the baseline period with the study period for the intervention and control units.

Figure: The change in acquisition rate, comparing the baseline period with the study period for the intervention and control units.

Here’s what’s BUGGing me about this study:

- The acquisition rate in both intervention and control study arms reduced (Figure). The acquisition rate reduction in the control arms may be due to improved compliance with admission screening, resulting in more accurate ascertainment of who required contact precautions.

- The significant reduction was achieved for MRSA but not for VRE. The authors suggest that VRE colonization may have been suppressed on admission and not detected, and flourished during antimicrobial therapy giving the impressive of acquisition. I wonder whether differences in the routes of transmission may also have contributed; for example, VRE seems to be substantially “more environmental” than MRSA. Another potential confounder is that, by chance, the prevalence of MRSA or VRE on admission to the intervention ICUs was more than double that in the control ICUs (22% vs. 9%). In actual fact, the raw rate of MRSA acquisition in the intervention ICUs was marginally higher than in the control ICUs during the intervention period (6.00 vs. 5.94 per 1000 patient days), even though the change in rate was significantly greater on the intervention ICU. Although adjustment was made for this difference in the analysis, it may have skewed the findings somewhat.

- The authors achieved remarkably high compliance with admission screening (around 95%), discharge screening (around 85%) and glove and gowning (around 85%). Each site had the luxury of a study coordinator and a physician champion to lead implementation, plus weekly feedback on screening compliance and visits from study investigators. Most ICUs would not be afforded these luxuries so I suspect that real-world compliance outside of the somewhat artificial study environment would be considerably lower. Indeed, an ID Week poster suggests that compliance with gowning in one US ICU was a ‘dismal’ 20%!

- Adverse events were not significantly higher in the universal glove and gowning arm, which may seem surprising prima facie. However, the reason why adverse events are more common for patients on contact precautions is that they are marginalized by being on contact precautions. If all patients are effectively on contact precautions, the time of healthcare workers would be spread evenly.

- Universal gloving is likely to result in universally bad hand hygiene compliance within the room during patient care; when healthcare workers feel protected, they are less likely to comply with hand hygiene and gloves are a good way to make healthcare workers feel protected. The increase in hand hygiene compliance on room exit is probably also a symptom of inherent human factors, since healthcare workers feel more ‘dirty’ when exiting the room of a patient with a higher perceived risk of MDRO ‘contamination’ (the so-called “urgh” factor).

- Healthcare workers had less time for patient care in the intervention arm because they were busy donning and doffing gloves and gowns. Interestingly, the authors suggest that fewer visits may be a good thing for patients, and may have contributed to their reduced chances of acquiring MRSA. This seems unlikely though, given the fact that VRE acquisition was not reduced. On balance, less contact with healthcare workers is likely to be bad for patients.

- The increased cost of universal glove and gowning was not evaluated and, whilst incrementally small, would be a substantial sum.

In summary, this study sets the standard in terms of rigorous assessment of an infection prevention and control intervention. Universal application of gloves and gowns is unlikely to do as much harm as universal administration of mupirocin, but it will not make a profound reduction in the transmission of MDROs. Therefore, I shouldn’t think many ICUs will be rushing to implement universal gloves and gowns on the strength of these findings.