The HIS / IPS Spring Meeting was on “What’s That Coming Over the Hill? Rising to the Challenge of Multi-Resistant Gram Negative Rods”. For those unfamiliar with the 2006 hit by the band “The Automatic”, the chorus goes: “What’s that coming over the hill? Is it a monster?”, hence the title to this post in light of the CDC-described “nightmare bacteria”! The full room (>250 delegates) illustrates how topical this issue is in the UK, and, indeed, globally. I enjoyed the day thoroughly, so thanks to all those involved in organizing the meeting.

Global Perspective – Professor Peter Hawkey

Prof Hawkey kicked off the day by considering how globalization has driven globalization in MDR-GNR, focusing mainly on ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Asia in particular is a hub of population (8/10 global ‘megacities’ are in Asia), antibiotic use (China was already the second largest consumer of imipenem back in 2002), aquaculture (Asia produces 62% of the world’s farmed fish) and travel. Prof Hawkey has been to India twice, and both times he returned colonized with an ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (incidentally, we should probably start calling these ‘EPEs’.) The UK receives almost 3 million international arrivals from India and Pakistan; 80% will carry ESBL-producing bacteria.1 So, since people carry their faeces with them, the global trend of increasing rates of ESBL faecal carriage is concerning.2 Medical tourism is a related and increasingly common risk for the importation of ESBL and carbapenemase producing bacteria.3 The increasing rates of carbapenem usage is largely the consequence of the emergence of ESBL. The CPE picture in the USA is bleak, and perhaps a sign of things to come, where only two states have not yet had confirmed reports.

Controlling a national outbreak of CRE in Israel – Dr Mitchell Schwaber

Dr Schwaber described the impressive and successful national intervention to control CRE in Israel.4 Dr Schwaber began in the beginning (Genesis 1) where the infection control landscape was ‘without form and void’ in Israel; the emergence of CRE changed that. The problems began in 2007 after which CRE spread like wild-fire. Local interventions failed and 22% of K. pneumoniae were carbapenem-resistant at the peak of the epidemic. Long-term and long-term acute care facilities were identified as particular issues, as has been recently reported in the USA.5 CRE carriage was found to be 17% at the height of the epidemic in long-term acute care facilities.6 In these “black-hole” CRE reservoirs, there is little focus on infection prevention and control, and social contact is a necessary part of the rehabilitation process, so complete segregation is unhelpful. Active detection, isolation of carriers, and staff cohorting were cornerstones of the effective intervention, but implementation was challenging and required a “top down” approach. Directives and feedback were administered through hospital chief executives. In Dr Schwaber’s view, Israel began their national programme too late and succeeded by the skin of their teeth. Israel is a small country with a well-funded and connected healthcare system. Will the national programme succeed elsewhere, even if implemented earlier?

Dissecting the Epidemiology of the Enterobacteriaceae and Non-Fermenters – Dr Jon Otter (who he?)

My exploration of the differences in the epidemiology of resistant Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters (mainly A. baumannii) was designed to prompt anybody tempted to conflate these two related problems to think twice; not all monsters are created equal. Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters do share the same response to the Gram-stain (more or less) and can be resistant to key antibiotics occasionally through shared mechanisms (principally the carbapenemases). But that’s about it. Otherwise they’re like chalk and cheese. (A. baumannii = chalk, which turns to dust; Enterobacteriaeae = a good cheese, which ultimately ends up in the gut.) You can read more about my talk and download my slides in yesterday’s post.

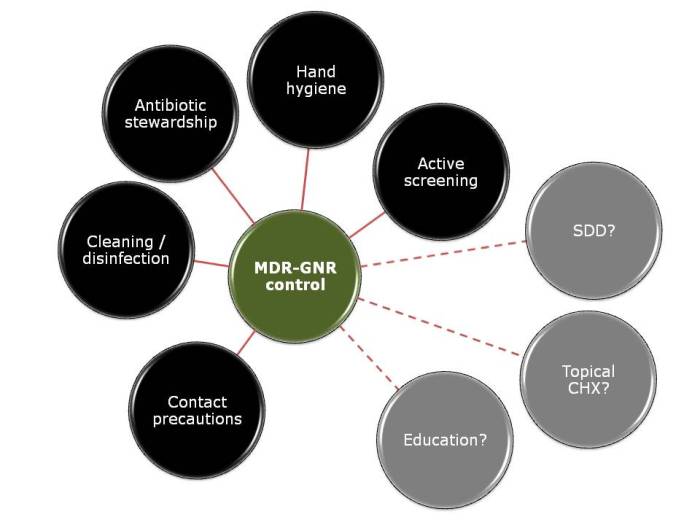

Infection prevention and control in the acute setting – Sheila Donlon

Sheila Donlon began by describing the low prevalence of MDR-GNR in Ireland. Around 2% of Enterobacteriaceae are carbapenem resistant, according to a recent point prevalence survey. Sheila’s comment that you need to go above and beyond standard precautions to control MDR-GNR resonated with Dr Schwaber’s talk, and with Dr Thom’s assessment from the SHEA meeting last week. Sheila spent the remainder of the talk discussing some of the approaches outlined in the Irish MDRO screening and control guidelines. Is hand hygiene for patients a black spot?7 How do we isolate patients effectively when we only have 20% single rooms? How and when should we cohort staff? What is the appropriate PPE? When should we consider ward closure, environmental screening or hydrogen peroxide vapour disinfection? Can we or should we discontinue contact precautions for CRE carriers?

Getting the message over: strategies for ensuring new guidance is put into practice – Dr Evonne Curran

Dr Curran outlined a frequent gap between theory and practice; guidance written in an ‘ivory tower’ without the correct stakeholders around the table will fail to influence practice. Even if the guidance is carefully crafted with implementation in mind, what happens on the wards will never perfectly reflect the guidance; we need a healthy dose of pragmatism. The addition of ‘adjectives’ don’t add clarity: ‘aggressive’, ‘robust’, ‘effective’, ‘strict’, ‘excellent’ are all vague; guidelines need to be specific.8 Dr Curran’s analysis of the differing definitions of ‘standard precautions’ was outstanding, and illustrates the challenges of local interpretation of international guidelines. We need to speak to front-line staff in a language they understand to implement guidance into practice.9

Dealing with Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter and Stenotrophomonas – Dr Beryl Oppenheim

Dr Beryl Oppenheim considered MDR Acinetobacter and Stenotrophomonas. These environmental non-fermenters are more of a niche problem than the resistant Enterobacteriaceae, but tend to be more resistant. Dr Oppenheim spent most of the time considering A. baumannii, which can be considered an “honorary Staphylococcus”; it’s more than a little Gram-positive!10 MDR A. baumannii combine inherent and acquired resistant mechanisms, survive for prolonged periods on dry surfaces and have the ability to produce biofilms.10-12 This makes them ideally suited for survival in the antibiotic-rich ICU environment, where they are most commonly problematic. MDR A. baumannii are also associated with infection following trauma in military hospitals.13 MDR A. baumannii is a problematic pathogen for a number of reasons. The epidemiology of hospital outbreaks can be difficult to dissect, with whole genome sequencing now the gold standard typing method.14 Contact isolation, perhaps even pre-emptive, is a must. Cleaning is critical, but the best approach is not obvious; ‘no-touch’ automated disinfection systems may be warranted sometimes.15 Active screening is rational but practically challenging: which sites to screen (a rectal swab alone is not sufficient) and which methods to use? Dr Oppenheim concluded by reflecting on the patchy prevalence of MDR A. baumannii (and Stenotrophomonas); it’s not a problem everywhere, but it’s a major problem where it rears its monstrous head.

Decontamination of instruments, equipment and the environment – Peter Hoffman

Peter Hoffman in his inimitable style reviewed the risks and environmental interventions specific to MDR-GNR. Contrary to the view of some, you can’t take a “leave them and they’ll die off approach” for Gram-negative rods; they will survive on dry surfaces.16 The issues covered by Peter included:

- Outbreaks linked to endoscopes (like the recent outbreak of CRE in Illinous).17

- The problems associated with designating equipment as single-use. Oftentimes only part can feasibly be single-use, meaning that there is a body of the equipment that needs to be decontaminated (and often isn’t). Portable ultrasound machines are a particular challenge. Safe working methods (one hand for the patient, one for the machine) are sound in theory, but challenging in practice (requiring considerable manual dexterity)! Ultrasound gel must be single-use sachets, regardless of cost implications.

- Don’t rely on privacy curtains with antimicrobial claims; they should be changed between MDR-GNR patients. (I wonder whether disinfection using advanced formulations of liquid hydrogen peroxide may be another option.18)

- Don’t rely on wipes for disinfecting mattress covers, especially ‘dynamic’ mattresses, which are full of bug-trapping folds. They probably don’t provide enough wetting (amongst other things).

- Should we invest in single-use pillows?19

- Water systems require careful management, particularly for P. aeruginosa.20

- Bed-pan washers represent a real risk for faecally-associated MDR-GNR. Why are they not more often foot pedal operated?

- Physiotherapy equipment on rehabilitation units is made for physiotherapy, not for effective decontamination. Careful design, with a dose of compromise, is required.

- Peter rarely believes negative results from environmental sampling due to a high risk of spot contamination.21

Peter’s somewhat provocative conclusion was that “there are no special decontamination requirements to control MDR-GNR.” I think the point here was that the issues outlined above are generic, such that addressing them would improve the safety of all patients, not just those with MDR-GNR. However, I fear that the conclusion could be misinterpreted to mean that increased focus on the potential environmental reservoir is not warranted when dealing with MDR-GNR. This does not concur with Peter’s citation of the surprising survival capacity of MDR-GNR, and Dr Oppenheim’s discussion of the ‘critical’ environmental reservoir for MDR A. baumannii.

Controversy: Decolonization and Staff Screening – Prof Peter Wilson

Prof Wilson began by challenging the feasibility of the recommended PHE screening approach. It would result in a lot of patients being identified for screening, and a high proportion of those held preemptively in contact isolation until confirmed negative. Prof Wilson suggesting prioritizing NDM and KPC producers over OXA-48 producers. Whilst I like this idea in principle, I am not sure that we have enough epidemiological data to support this distinction. The recent ESCMID guidelines are a useful resource on screening approaches, if a little wordy.22 Staff screening should be avoided, unless a member of staff is clearly implicated in transmission; what would you do with a carrier? Peter’s view is that clearance swabs are a waste of time, and advocated a “once positive, always positive” approach to CRE. “Once positive, always positive” works in a low prevalence setting, but comes increasingly unstuck as prevalence increases. Is selective decontamination the answer?23,24 Not really; whilst individual patient mortality is decreased, neither selective oral decontamination (SOD) nor selective digestive decontamination (SDD) decolonize carriers. The potential collateral damage of SOD and SDD when applied to MDR-GNR is clear: hastening the arrival of pan-drug resistance.

Therapeutic Options and Looking to the Future – Prof David Livermore

The resistance profile of MDR-GNR leaves few antibiotic classes left; sometimes only colistin, and colistin-resistance is emerging in both Enterobacteriaceae25 and non-fermenters26. Indeed, a national Italian survey found that 22% of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae were resistant to colistin.27 Leaving aside the risk of nephrotoxicity,28 colistin monotherapy results in the development of colistin resistance.29 Another issue relates to challenges in laboratory testing. Apparent MDR-GNR susceptibility depends on the testing methods used, and may not match clinical outcome:30 the mice who died despite antibiotic treatment in one study would surely query the EUCAST and CLSI breakpoints that defined their K. pneumoniae isolates as susceptible.31 The use of existing and more creative combinations of existing antibiotics can help. Also, a small number of new antibiotics are in development (although we have run out of truly novel targets, meaning that they are modifications of existing classes). A more promising approach is the use of antibiotics combined with β-lactamase inbibitors, but these are currently at a fairly early stage of clinical trial.32

Summary and points for discussion:

- People carry their faeces with them, so the global trend of increasing rates of carriage of resistant Enterobacteriaceae is concerning.

- Will the successful national CRE control programme in Israel (a small country with a well-funded, connected healthcare system) be feasible elsewhere?

- Can we safely ‘de-isolate’ CRE carriers? Israel has managed to do it, but I suspect the answer will depend on your level of prevalence and pragmatism.

- Do not conflate the epidemiology of resistant non-fermenters and Enterobacteriaceae; they’re like chalk and cheese!

- Do we have the right stakeholders around the table to write national guidance, and is it written with implementation in mind?

- How best to address the environmental reservoir for A. baumannii and, to a lesser extent, CRE?

- We need to carefully consider the likely collateral damage before applying SOD / SDD when applied to MDR-GNR: pan-drug resistance!

- How far can combinations of existing antibiotics, novel combination and new treatment options go in treating MDR-GNR? Probably not that far; prevention is better than cure.

References

1. Tham J, Odenholt I, Walder M, Brolund A, Ahl J, Melander E. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in patients with travellers’ diarrhoea. Scand J Infect Dis 2010; 42: 275-280.

2. Woerther PL, Burdet C, Chachaty E, Andremont A. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26: 744-758.

3. Hanefeld J, Horsfall D, Lunt N, Smith R. Medical tourism: a cost or benefit to the NHS? PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e70406.

4. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. An ongoing national intervention to contain the spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 697-703.

5. Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K et al. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 1246-1252.

6. Ben-David D, Masarwa S, Navon-Venezia S et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in post-acute-care facilities in Israel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32: 845-853.

7. Landers T, Abusalem S, Coty MB, Bingham J. Patient-centered hand hygiene: the next step in infection prevention. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40: S11-17.

8. Rouse W, Fuzzy Models of Human Problem Solving, in Advances in Fuzzy Sets, Possibility Theory, and Applications, Wang P., Editor. 1983, Springer US. p. 377-386.

9. Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ 2008; 337: a1714.

10. Wagenvoort JH, Joosten EJ. An outbreak Acinetobacter baumannii that mimics MRSA in its environmental longevity. J Hosp.Infect 2002; 52: 226-227.

11. Strassle P, Thom KA, Johnson JK et al. The effect of terminal cleaning on environmental contamination rates of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40: 1005-1007.

12. Espinal P, Marti S, Vila J. Effect of biofilm formation on the survival of Acinetobacter baumannii on dry surfaces. J Hosp Infect 2012; 80: 56-60.

13. Scott P, Deye G, Srinivasan A et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex infection in the US military health care system associated with military operations in Iraq. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 1577-1584.

14. Lewis T, Loman NJ, Bingle L et al. High-throughput whole-genome sequencing to dissect the epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a hospital outbreak. J Hosp Infect 2010; 75: 37-41.

15. Otter JA, Yezli S, Perl TM, Barbut F, French GL. Is there a role for “no-touch” automated room disinfection systems in infection prevention and control? J Hosp Infect 2013; 83: 1-13.

16. Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2006; 6: 130.

17. Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Notes from the Field: New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography – Illinois, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014; 62: 1051.

18. Rutala WA, Gergen MF, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Williams DA, Weber DJ. Effectiveness of improved hydrogen peroxide in decontaminating privacy curtains contaminated with multidrug-resistant pathogens. Am J Infect Control 2014; 42: 426-428.

19. Reiss-Levy E, McAllister E. Pillows spread methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Med J Aust 1979; 1: 92.

20. Loveday HP, Wilson J, Kerr K, Pitchers R, Walker JT, Browne J. Pseudomonas infection and healthcare water systems – a rapid systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2014; 86: 7-15.

21. Lerner A, Adler A, Abu-Hanna J, Meitus I, Navon-Venezia S, Carmeli Y. Environmental contamination by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51: 177-181.

22. Tacconelli E, Cataldo MA, Dancer SJ et al. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20 Suppl 1: 1-55.

23. Price R, MacLennan G, Glen J. Selective digestive or oropharyngeal decontamination and topical oropharyngeal chlorhexidine for prevention of death in general intensive care: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 348:

24. Daneman N, Sarwar S, Fowler RA, Cuthbertson BH, Su DCSG. Effect of selective decontamination on antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 328-341.

25. Bogdanovich T, Adams-Haduch JM, Tian GB et al. Colistin-Resistant, Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Belonging to the International Epidemic Clone ST258. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 373-376.

26. Agodi A, Voulgari E, Barchitta M et al. Spread of a carbapenem- and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 clonal strain causing outbreaks in two Sicilian hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2014; 86: 260-266.

27. Giani T, Pini B, Arena F et al. Epidemic diffusion of KPC carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Italy: results of the first countrywide survey, 15 May to 30 June 2011. Euro Surveill 2013; 18:

28. Drekonja DM, Beekmann SE, Elliott S et al. Challenges in the Management of Infections due to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35: 437-439.

29. Lee GC, Burgess DS. Treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) infections: a review of published case series and case reports. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2012; 11: 32.

30. Weisenberg SA, Morgan DJ, Espinal-Witter R, Larone DH. Clinical outcomes of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae after treatment with imipenem or meropenem. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009; 64: 233-235.

31. Mimoz O, Gregoire N, Poirel L, Marliat M, Couet W, Nordmann P. Broad-spectrum beta-lactam antibiotics for treating experimental peritonitis in mice due to Klebsiella pneumoniae producing the carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2759-2760.

32. Drawz SM, Papp-Wallace KM, Bonomo RA. New beta-Lactamase Inhibitors: a Therapeutic Renaissance in an MDR World. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 1835-1846.

I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).

I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).