My head is full and my wallet is light following an enjoyable week in Geneva for the 2nd ICPIC conference (25th – 28th June 2013). I missed out on the inaugural ICPIC in 2011, so I was pleased to make the 2nd ICPIC. I was a little concerned that it would be a “hand hygiene fest”, but the programme had a good balance between hand hygiene and other areas of infection prevention and control. The conference had more than 900 delegates from 89 nations with 97 oral presentations and 427 posters. Congratulations to the organizing committee for arranging an interesting and stimulating conference. The conference abstracts are freely available in an ARIC supplement and the slides can be purchased by contacting the conference organizers.

Sadly I was unable to clone myself and attend every session, but this will give you a flavour…

TUES 25TH JUNE – OPENING SESSION

The opening session focused on viruses with pandemic potential, with an impressive introduction from some Genève luminaries and a personal video from Dr Margaret Chan (WHO Director General).

David Heymann – The legacy of SARS

Dr Heyman presented an engaging first-hand overview of the early reports of SARS, illustrating that it was predominately a healthcare-associated infection. The legacy of SARS according to David Heymann:

- Improved global surveillance, for example, the advent of new surveillance methods and networks such as Google outbreak software.

- “Research ready” capacity. The emergence of new microbial threats promotes the requirement for a research network ready and waiting to swing into action, such as the Oxford University Institute for Emerging Infections.

- Economic impact. SARS cost Hong Kong 4% of GDP.

- Understanding animal reservoirs. HIV, SARS, Avian Influenza, MERS-CoV (?) and most other pathogens with pandemic potential have emerged from animal reservoirs.

Wing Hong Seto – Infection control before and after SARS

Dr Seto’s thesis was that the spread of SARS in hospitals was due to poor basic infection control practice, evidenced by his own institution’s low rate of staff infection stemming from his enthusiastic education and awareness campaign. Put another way, sloppy infection control cost healthcare professional’s their lives. Dr Chan stated earlier that “the thermometer won the war against SARS”, which resonated with Dr Seto’s “getting the basics right” message. The experience of SARS has resulted in an increase in focus on infection control in Asia region, resulting in more investment, higher infection control staff : bed ratios and centralized expert committees. However, there has been some overreaction too, with very expensive structural changes to hospitals without proper consultation. Dr Seto’s enthusiasm truly lit up the stage.

Laurent Kaiser – influenza, coronavirus and emerging viruses: can we predict the unexpected?

A detailed overview of the genetic basis of these pandemic viruses that are associated with respiratory disease, aerosol / droplet spread, seasonal patterns, an RNA genome and rapidly emerging strains. The most interesting part of the talk for me was a consideration of how long it takes to “humanize” an animal virus. Whilst it’s difficult to be sure, it seems that it takes decades (or perhaps even centauries) for the necessary amount of recombination and mutation to occur for a virus to jump to humans and spread efficiently. For example, the H1N1 virus seems to be a mosaic of three viruses that may trace its origins to the 1918 pandemic. In this age of almost instant phylogeny, it may not be long before we can start watching viruses evolve in real time.

Keiji Fukuda – Latest news from MERS-CoV and H7N9

Dr Fukuda (WHO) gave a brief historical view of HIV, SARS, H5N1 and H1N1 to illustrate how a pandemic response looks in relation to the two current threats: H7N9 and MERS-CoV. A relatively small number of N7N9 (132) and MERS-CoV (70) cases have been reported so far, but their high mortality rates are alarming. Interesting unanswered questions:

- Are we at a suitable level of readiness to respond?

- How should we name pandemic viruses?

- How do we handle intellectual property that emerges during pandemic response?

Robert Wachter – Embedding infection prevention into medical training and the patient safety agenda

Dr Wachter explained that the patient safety movement began with infection control, but is now predominant in the US. Infection control should seek to embed itself within the core values of patient safety: quality and value. Dr Wachter explained some seminal moments in the development of the patient safety movement: the realization that medical errors were killing the equivalent of a jumbo jet of Americans each day and that zero is possible. Perhaps it would be helpful to see non-compliance with hand hygiene as a medical error?

WEDS 26th JUNE

Hyde Park corner debate: decrease of MRSA in the UK successful infection control or natural decrease? Stone v Wylie

Unusually, I found myself in disagreement with both the pro and con position presented in this debate!

Dr Stone laid out the case for the pro, largely based on this study. The main conclusions from the study were that MRSA bacteraemia and C. difficile rates fell in association with increased use of alcohol based hand products and soap, respectively, but MSSA bacteraemia rates did not fall; and that the Department of Health Implementation Teams and the Healthcare Act were associated with MRSA bacteraemia. It’s odd that rates of MSSA bacteraemia did not fall in conjunction with the increased use of alcohol based hand products. Also, I wonder whether a “breakpoints” type model would have been more suitable for this dataset?

Dr Wylie tried to convince us that the national reduction in MRSA was due to natural variation. He used the wax and wane of an unusual MRSA clone in the 1970s in Denmark as evidence that clones come and go. However, this was controlled by a focused national intervention, which rather defeated Dr Wylie’s argument. He offered three alternative plausible explanations:

- Incompletely understood interventions. [Not an alternative explanation per se, just saying that the decline was associated with the interventions, just not in the way that Dr Stone said.]

- Changes in host immunity.

- Changes in antibiotic use.

The one alternative explanation that Dr Wylie mentioned only in passing was increased use of chlorhexidine. This seems to be a much more plausible alternative explanation, so I’m not sure why this was not explored in more detail. It would also go some way to explain the relatively rapid decline in EMRSA-16 vs. EMRSA-15.

It just seems totally implausible that a national campaign to control MRSA would happen to correspond with a natural decline in MRSA. There will always be some uncertainty in interpreting epidemiological trends. Bradford-Hills famous criteria are oft cited, but worth noting that Bradford-Hill once said “my criteria cannot provide indisputable evidence – they help us to make up our minds”.

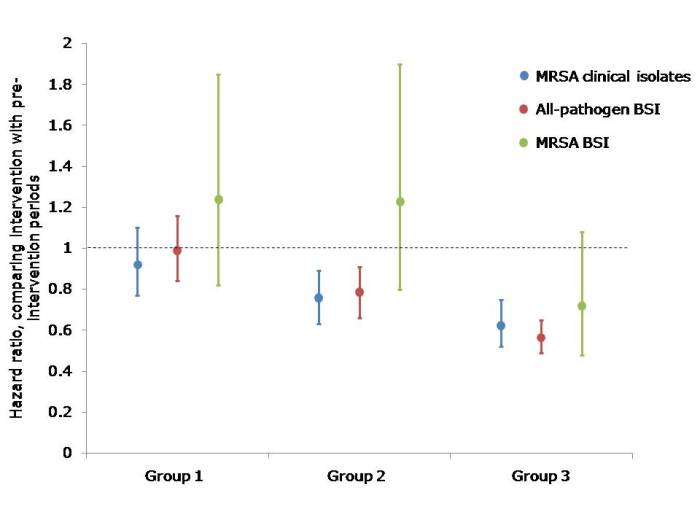

The impact of the US Veterans Affairs initiative: too nice to be true? Samore v Bonten

Dr Samore presented a robust case that the interventions throughout the VA network in the US explained the reductions in this NEJM study by Jain et al. He included a fair overview of the study limitations (principally no control group!). Interesting to note that the admission prevalence of MRSA was around 15% in the Jain study, compared with just 2% in London. Whilst there are important differences in the patient groups admitted to VA hospitals in the USA and a London teaching hospital, the magnitude of the difference is striking and may explain in part the large reductions in transmission achieved.

Dr Bonten took the opportunity to play devil’s advocate for several recent high-profile MRSA papers. I would have preferred a more detailed critique of the Jain et al. study, which was, after all, the subject of the debate! Dr Bonten’s group have published a reanalysis of the Jain data challenging their findings. Dr Bonten concluded, rather depressingly, that we still don’t have any proven interventions to control MRSA, apart from universal mupirocin and chlorhexidine, or “selective digestive decontamination”. Neither strategy get my vote due to the obvious risk of the development of resistance; we need to work harder to evaluate the most effective ways to target our precious remaining antibiotics in order to preserve their activity.

Antoine Andremont – The gut microbioma: mother of all troubles?

This fascinating lecture outlined the challenges associated with resistant bacteria in the gut. The gut houses a phenomonial number of bacteria (up to 1014 cfu per mL), predominantly non-pathogenic anaerobes (1010), other commensals (106-109) and resident enterobacteria (106). To qualify these numbers, the population of Paris is around 106 (number of enterobacteria) whereas the number of humans that have lived on earth for the past 3 million years is 1010 (number of non-pathogenic enterobacteria).

Antibiotic resistant enterobacteria can be found in the gut, comprising somewhere between 0 to 100% of all enterobacteria, which varies over time with diet and antibiotic usage. The presence of resistant enterbacteria is likely to result in widespread shedding into the environment based on VRE data.

The carriage of resistant bacteria in the gut is probably impossible to eliminate, but could be addressed by the following:

- Reduce the use of antibiotics.

- Increase hygiene and sanitation.

- Decolonization (although attempts to decolonize using antibiotics and probiotics have failed thus far).

- Moderate counts of resistant bacteria in the gut. There are several approaches here, for example the co-administration of a recombinant enzyme to inactivate antibiotics in the gut or the use of an “antibiotic sponge”.

George Daikos – The how’s and where’s of colistin resistance

Dr Daikos explained how polymyxins have been ‘reinvented’ to tackle multidrug-resistant Gram-negative rods, citing data from this Medscape report:

The antibiotic works through electrostatic interaction with the cell membrane predominately via lipopolysaccharides which facilitates the update of colistin and subsequent cell death. Resistance can be intrinsic, adaptive or acquired, and heteroresistance has been reported. Heteroresistance could be greatly underreported: a recent SENTRY study found that 23% of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter were heteroresistant to colistin.

Colistin resistance is emerging fast in certain areas; 23% of K. pneumoniae are now resistant to colistin in Greece. The fact is, we still have a lot to learn about how to use colistin most effectively, it’s mode of action, resistance mechanisms and how to detect reduced susceptibility in the clinical lab.

Matthew Samore – C. difficile in the community: community-onset or silent reservoir?

Dr Samore began with some entertaining analogies to illustrate the various ways to understand the interchange between hospital and community C. difficile: Gwyneth Paltrow in Contaigon, an Iceberg, a Straw Man and a Bathtub! Several studies identify apparently rising rates of CDI in the community yet carriage by healthy community members remains rare (2-3%). Combined with the finding that C. difficile colonization increases with length of stay make me think that CDI remains a predominantly hospital problem with some community-onset cases. Indeed, the recent JAMA Intern Med study of apparent CA-CDI only evaluated healthcare-exposure for three months prior to the CDI episode, and most patients had some healthcare exposure. I was surprised that Dr Samore did not mention high rates of carriage in neonates, which seems to be a genuine community-based reservoir doubtless resulting in a background of community acquisition of C. difficile.

There’s perhaps a parallel with MRSA here. For a long time, people talked about “community-acquired” MRSA, when it was really MRSA transmitted in the hospital manifesting in the community. However, there did come a phase shift in the epidemiology of MRSA with the emergence of distinct CA-MRSA strains that began to transmit outside of hospitals. So, we shouldn’t rule out CA-CDI as a possibility, but I don’t think we’re there yet.

Walter Zingg – C. difficile control in the hospital

Dr Zingg considered the various factors in the transmission of C. difficile: contamination of patients’ skin, hands, air and surfaces; proximity to other patients and colonization pressure. The control interventions highlighted were isolation, hand washing, single use thermometers, environmental disinfection using a sporicide (including adjunctive hydrogen peroxide vapour where feasible) and antibiotic restriction. I was surprised not to hear of the role of molecular diagnostics in C. difficile control. The switch to more accurate molecular diagnostics has facilitated improved identification of infected patients, and hence more successful isolation.

Innovation Academy

Or should I say, the ‘Infection Control Dragon’s Den’. Just like the TV show, 15 innovations were granted a 3 minute pitch followed by two minutes of quick-fire questioning from the expert panel and audience. Prof Pittet ensured that each presenter stuck to their 3 minutes, which was entertaining in itself. Five finalists were selected for an extended pitch the following day and a winner selected by the expert panel. A classic quote from Einstein set us off: “If at first the idea is not absurd, it is not good”! I’ve listed the finalists below along with some details of all 15 pitches:

- The winner: ‘A novel immediate pre-operative decolonization strategy reduces surgical site infections.’ Pre-operative decolonization using photodisinfection combined with chlorhexidine bathing. High compliance, well tolerated and saved money. My only problem is that it was difficult to delineate the relative impact of photodisinfection (novel innovation) from chlorhexidine (already well established). Nonetheless, a worthy winner!

- Second place: ‘A novel antiviral technology for air filtration.’ An external antiviral layer for masks. The agent is only effective against enveloped viruses and the need was not well defined. Is this to prevent penetration of infected viruses through the mask or to reduce the risk of hand contamination when removing the mask?

- Third place: ‘A novel antibacterial material for transparent dressings.’ A small trial (n=10) of a polyurethane dressing with antimicrobial properties.

- Fourth place: ‘Can Dav132, a medical device targeting an adsorbent to the late ileum, decrease significantly the impact of antibiotics on the fecal microbiota?’ A medical device to “mop-up” antibiotics in the gut with huge potential to suppress resistant gut flora.

- Fifth place: ‘Infection Control Enclosure (ICE) pod: meeting the need for more single rooms’. [COI – I am listed as a co-author on this one!] A way to increase single room capacity in a multi-occupany bay setting.

The other pitches:

- ‘Reduction of resistance by sublingual administration of antimicrobials.’ A gutsy musical presentation of an old paper from the 1970s. The only problem was, not a shred of data to support the innovation!

- ‘A new generation of hybrid biomaterials for antimicrobial medical devices.’ Impregnated silicon for medical devices to reduce bacterial adhesion.

- ‘Electronic hand hygiene monitoring for the WHO 5-moments method.’ An automated way to monitor hand hygiene compliance by placing a chip in each dispenser to measure usage in real-time and compare with expected usage patterns generated by an algorithm.

- ‘Evaluation of the efficacy of a novel hydrogen peroxide cleaner disinfectant concentrate.’ ‘Accelerated’ hydrogen peroxide is an impressive product, but it’s been around for a long time so has no place in the innovation academy!

- ‘A new genre of surface disinfectant with long residual bactericidal activity.’ A polymer antimicrobial surface film that can be impregnated with various antimicrobials (I think – wasn’t particularly clear on this point)!

- ‘Development of an electronic dashboard to assist surveillance’. The e-dashboard ticks some important boxes for me, not least because it’s free! However, how does it compare with proprietary systems in terms of functionality?

- ‘Combining electronic contacts data and virological data for studying the transmission of infections at hospital.’ Tagging patients and staff with RFID badges to track movements and then trace proximity (though not contact per se). Useful Harry Potter “Marauders’ Map” style technology.

- ‘New holistic approach to determine the infection risk profile of a hospital; visualized in an easy-to-read plot’. A way to produce a visual, fairly intuitive ward-level report to easily identify areas for improvement. A useful tool, but lacks the novelty of other contenders.

- ‘Organisational transformation – the application of novel change techniques & social media understanding to motivate infection-prevention activists.’ A pitch from the Infection Prevention Society using collaboration focused on social media to effect organizational change following a “pre-mortem” self-assessment.

I particularly enjoyed the Innovation Academy. The Dav132 antibiotic gut “sponge” got my vote as the most important innovation.

THURS 27th JUNE

Meet the experts (Boyce and Dettenkofer): Controversial issues about environmental cleaning and disinfection

Dr Dettenkofer began with a framework for understanding hospital cleaning and disinfection needs. His position is that low-level disinfection is the main requirement. However, the presence of C. difficile spores means that a sporicide (i.e. high-level disinfectant) is necessary on occasion. So, is the requirement for hospital disinfection high or low level disinfection? Dr Dettenkofer talked briefly about the debate over whether surface disinfection is required at all in hospitals, when cleaning (without the use of a chemical disinfectant) is often sufficient. Interesting to hear that Dr Dettenkofer has begun to use a liquid hydrogen peroxide disinfectant in his hospital. Finally, the question of whether a two-step process (cleaning followed by disinfection) is necessary. It’s difficult enough to get good compliance with one round of cleaning or disinfection, let alone assuring adequate coverage of first a cleaning agent, then a disinfectant. Effective combination products are required urgently.

Dr Boyce discussed:

- What is the ‘best’ surface disinfectant? He considered aldehydes, QACs, phenolics, chlorine releasing agents, hydrogen peroxide and peracetic acid. The conclusion: all have pros and cons!

- So, how to assess cleaning performance? Visual assessment, microbiological cultures, ATP or fluorescent markers. These are not mutually exclusive and, again, all have pros and cons.

- Finally, which “no-touch” room disinfection system to use? Hydrogen peroxide vapour, aerosolized hydrogen peroxide, UVC, pulsed-xenon UV and other systems are available. You guessed it, all have pros and cons!

Control of hyperendemic Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriacae

Abdul Ghafur – The Indian perspective

A passionate presentation by Dr Ghafur beginning with 50% attributable mortality in his neutropaenic patients due to CRE resulting from carbapenem and colistin abuse; mortality for pan resistant CRE approached 100%. Dr Ghafur discussed some of the underlying problems in India: poor sanitation, high rates of carriage of resistant bacteria (80% CR Acinetobacter and 40% CR Klebsiella), reflecting on the fact that tight local antimicrobial prescription will not save you if everyone else is sloppy. How to treat pan-drug resistant CRE? “Pentatherapy” using a 5 drug cocktail and a prayer. (Actually, there is probably some synergy between colistin and other antibiotics so pentatherapy isn’t as daft as it sounds.)

Yehuda Carmeli – An Israeli perspective

Israel experienced a dramatic initially clonal national outbreak of CRE (KPC CC258) in 2006. Analysis of data from the outbreak indicated that compliance with cohorting correlated tightly with CRE transmission; more data that getting the basics right works. The risk-based screening that was implemented detected a low prevalence of carriage (5% from long-term care facilities, 0.5% from other high risk groups) but was considered worthwhile to prevent outbreaks. Dr Carmelli raised several points for discussion:

- Media interest. It seems to me that the media can be a friend or foe in dealing with outbreaks and wider healthcare issues. If left unbriefed, they will be a foe. But if properly briefed, they can be a powerful ally.

- Emergence of different CRE genes (OXA-48 and NDM-1) in Israel with different epidemiological associations than KPC.

- Dealing with the long-term care facility reservoir.

- Non-compliance with basic infection control.

- “Eye off the ball” syndrome, where hospital administrators only respond to current threats.

The national successful response in Israel is an encouraging success story. However, Israel has a population of 8 million, with only 31 hospitals. Can successful national control strategies be implemented in larger countries with an inferior healthcare infrastructure and national debt problems such as Greece and Italy?

Achilles Gikas – The Greek perspective on CRE: from surveillance to control

Dr Gikas described the development of the CRE epidemic in Greece with overlapping outbreaks of VIM and KPC carriers, and how CRE is now a “frequent flyer” travelling around the world. Reassuringly, there are some local success stories in Greece where focused interventions have reduced rates of CRE, but, mindful of Dr Kulakkattil’s comment that “no hospital is an island”, concerted national efforts are required to grasp this rampaging Hellenic bull by the horns.

Environmental decontamination with hydrogen peroxide vapor – does the effect evaporate over the Atlantic? Perl v Huttner

Having spent some 10 years researching this particular topic, needless to say I was looking forward to this debate. The debate was not particularly well framed. Was this about most of the studies of HPV (and all of the controlled studies with a clinical outcome) coming from US hospitals? Or that many European countries have a lower proportion of single rooms, which makes the application of HPV more challenging? Or a wider debate about whether to consider “no-touch” disinfection (NTD) systems at all? I felt that Dr Perl addressed the more general questions while Dr Huttner focused on HPV studies, which rather took the wind out of the sails of the debate.

Dr Perl summarized data that pathogens are shed into the environment, they survive for extended periods, persist despite conventional cleaning and disinfection and improving conventional methods helps, but transmission continues. Hence, NTD systems and specifically HPV are warranted in some circumstance. Dr Perl acknowledged the lack of RCTs but showed convincing data that HPV eliminates pathogens from surfaces and reduces transmission, and fulfils Bradford-Hill’s criteria of causation.

Dr Huttner began like Dr Perl by considering some things that evaporate over the Atlantic: big cars, big guns and flavoured coffee to name but a few! His American wife gives him an unusually sharp perspective on trans-Atlantic issues. Dr Huttner had clearly done his homework and read the various HPV studies in detail. He presented a series of good points, although I didn’t feel that he constructed a particularly coherent argument. To address some specific points:

The short debate (30 mins) did not allow time for the authors to present a rebuttal, which was a shame, but it was a stimulating session.

FRI 28th JUNE

Controlling ESBLs – a global perspective

Jean-Christophe Lucet – Europe

Dr Lucet began by demonstrating a startling increase in the proportion of invasive isolates that carry ESBLs in Europe comparing 2005 with 2011. He reviewed data that ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae is much more likely to be transmitted in hospitals than ESBL-producing E. coli, perhaps due to an increased capacity for environmental survival. Effective interventions are difficult to recommend due to lack of RCTs, outbreak settings (and regression to the mean), publication bias and control bundles. However, Dr Lucet concluded:

- Hand hygiene: yes.

- Active surveillance cultures and contact precautions: equivocal.

- Cohorting: yes during outbreaks.

- Environmental control: less important than for other pathogens.

- Selective digestive decontamination (SDD) / universal use of chlorhexidine: equivocal. My view is that SDD should not be used – the indiscriminate use of antibiotics will drive further resistance.

Wing-Hong Seto – Far East / Asia

Carriage rates of ESBLs in E. coli and K. pneumoniae are alarmingly high in parts of Asia, reaching >50% in India and Vietnam. Dr Seto suggested that single room isolation is more important for Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacterial pathogens based on relatively higher recovery of Gram-positive bacteria from the hospital environment. However, lactose non-fermenting Gram-negatives such as Acinetobacter seem to ‘mimic’ Gram-positive bacteria in terms of their environmental survival, and even the Enterobacteriaceae can survive for days to weeks to months on surfaces. So, I would argue that priority for single room isolation should be dictated by an assessment of local epidemiology and risk, not the survival properties of various bacteria.

Andrew Stewardson – Australia

Carriage rates of ESBL-producing bacteria are lower in Australia than in nearby Asian countries (<10% in the hospital population and <5% in the community). Dr Stewardson presented some interesting Australian data showing that rigorous implementation of standard precautions and antibiotic restriction programmes can result in impressive reductions of ESBL producing K. pneumoniae in hospitals.

Final reflections

My first ICPIC was an enjoyable experience. Highlights included the opening session learning lessons from SARS, the entertaining innovation academy and some grim updates on the ‘rampaging Hellenic bull’ that is CRE. Regretfully, I didn’t get to see a single poster and missed few concurrent sessions (including the review of best papers by Eli Perencevich and Andreas Widmer – they’ve published their slides here). Of all the analogies presented at the conference, I think the most useful was the ‘Infection Control Football Club’ by Dr Sheldon Stone. Hand hygiene is the goal keeper (i.e. last line of defence). But you won’t have a winning football team with just a goal keeper. No matter how good they are, they will never stop every shot.

An outbreak report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases tells the fascinating story of a norovirus outbreak in a car (auto*) dealership in Oregon that was initially thought to be foodborne, but was eventually traced to contaminated surfaces on a baby changing table (diaper changing station*) in a public toilet (restroom*). The outbreak had a startlingly high attack rate, affecting 75% of 16 employees who attended a team meeting. A thorough investigation of the restaurant that provided the sandwiches for lunch turned out to be a blind alley following the recollection of a staff member of a toddler with “spraying” diarrhoea using the baby changing table in the public toilet of the dealership. The (generous) mother left the mess for the staff member to clean up, which was accomplished using, wait for it, dry paper towels.

An outbreak report in the Journal of Infectious Diseases tells the fascinating story of a norovirus outbreak in a car (auto*) dealership in Oregon that was initially thought to be foodborne, but was eventually traced to contaminated surfaces on a baby changing table (diaper changing station*) in a public toilet (restroom*). The outbreak had a startlingly high attack rate, affecting 75% of 16 employees who attended a team meeting. A thorough investigation of the restaurant that provided the sandwiches for lunch turned out to be a blind alley following the recollection of a staff member of a toddler with “spraying” diarrhoea using the baby changing table in the public toilet of the dealership. The (generous) mother left the mess for the staff member to clean up, which was accomplished using, wait for it, dry paper towels.