The 13th International Federation of Infection Control (IFIC) meeting took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina in October 2013. A colleague who attended sent me some notes from the meeting, which I was not able to attend. I found the notes useful, so thought I’d share them (albeit a little late)!

Pro-Con debates

The first was on government regulations in infection control. The Pro delivered by H Baguio from Uruguay and Con by M Borg from Malta. H Baguio gave examples where government regulations have had impact on infection rates, citing the case of MRSA in the UK and reductions in bacteraemia, UTI and KPC prevalence after governmental regulation and auditing introduced in Uruguay. M Borg gave examples were governmental interventions did not improve the situation: for example, a 5x increase in the cost of medical waste disposal due to an insistence on considering it hazardous, when much could be considered non-hazardous. Also, there is a suggestion that since CLABSIs became non-refundable by the US government, many hospitals have started using peripheral lines over central lines to avoid financial loss. Another possible consequence is a less active attempt to detect infections in US hospitals, and a reticence to admit high-risk patients to avoid infection. However, in general the debate was not really pro-con as both admitted that some sort of government regulation is needed but they were not the only solution. This was reflected in the final results: 50% pro and 50% con.

The second debate was about universal vs. targeted MRSA screening. T. Boswell was arguing for universal screening, while E Lingaas of Norway was for targeted. There were good arguments from both sides but the vote suggested a swing towards targeted screening. I think the debate would have been more interesting if it as about universal screening for all pathogens of interests such as the emerging MDR Gram-negative bacteria. Whether you choose universal or targeted screening will depend on your country and healthcare setting. In countries with high carriage prevalence, universal screening will be more beneficial, especially when using quick and cheap diagnostic tests. For countries with low prevalence, targeting screening probably makes more sense. However, choose your targeted screening approach carefully: I performed a study recently where we found that reverting to our targeted screening approach would miss around 50% of carriers!

Selected talks

Stella Maimone (Buenos Aires, Argentina): “Infection control: the other side of the moon”

Stella was the first registered infection control nurse in Argentina. Most IC nurses in Argentina have been trained by her. She gave a general talk on IC in Latin America (LA) based mainly on the differences between Latin America and developed countries in IC. She noted that most LA countries ministries of health have some sort of infection surveillance systems including in Argentina. However, the data are not publicly available (at least in Argentina) which is a major difference between LA vs. USA and Europe.

Although LA countries are aware of the cost of HAIs, they have limited resources and it is not possible to reproduce the same IC policies that are implemented in US and UK (e.g. CDC guidelines) in LA. The reasons for that are: limited resources, different culture, LA people don’t like to be controlled (i.e. governmental regulations will have limited effect), and LA people think short term hence IC policies aimed at results in the distant future will not be adopted.

Hence for effective IC policies in LA, the limited resources of the countries/hospitals, the wider culture of society, and the ‘micro culture’ of the healthcare community must be taken into consideration.

Maria Clara Padoveze (University of Sao Paulo, Brazil): “Help! An outbreak!”

This was an interactive session with Q & A throughout. The informative talk covered outbreak definition and detection, but did not address outbreak control and infection control interventions in detail, which was a shame. Maria highlighted a useful website for performing quick literature reviews on various outbreaks from round the world: www.outbreak-database.com. This gives you an up-to-date (ish) report of outbreaks from around the world. If you register (free) you can access advance search where you can search per country for example.

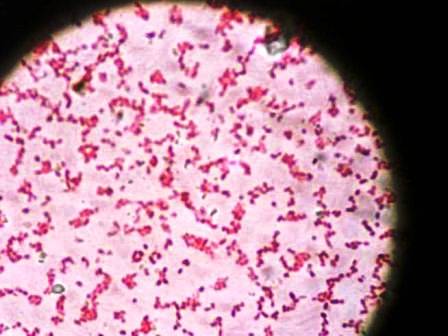

Celeste Lucero (Argentina): “MDROs: a new world war”

This helpful overview began with an overview of how organisms acquire multidrug resistance. Celeste mentioned the WHONET-Argentina, which is a WHO Collaborating Centre for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in the country. Celeste offered a few examples including the CTXM-2, which is endemic in Argentina, and the emergence of CTXM-15 and OXA-163. She also mentioned that many Acinetobacter baumannii are now only treatable by Tigicycline and Colistin, and that rates of KPC have been increasing since 2010. To compound matters, Argentina had its first reported NDM-1 in 2013. I left the talk without a clear picture of prevalence of MDROs in Argentia, which may reflect the paucity of accurate epi data.

Martin Kiernan (UK): “Taking infection prevention to the next level”

Martin gave a talk on the UK experience in IC, citing examples of the impressive reductions achieved in the UK for MRSA and C. difficile, and the various interventions to achieve these reductions. He mentioned that the problem now is MDR Gram-negatives such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. His talk focused on how to change the IC culture in a hospital, including getting everyone engaged.

Syed Sattar (University of Ottawa, Canada): “The role of high-touch environmental surfaces in the spread of HAI: strategies to minimize the risks”

The talk began by outlining the factors that determine the risk of transmission from an environmental surfaces: probability of contamination; ability of pathogen to survive on the surface; transmission potential (e.g. porous surfaces are poor at transmitting pathogens, hence focus more on hard surfaces); location and frequency of direct contact with the surface (e.g. via hands or mucous membranes). He then went to define which pathogens to focus on. He warned not to focus on the high profile pathogens or the “pathogen of the month” such as HIV or H1N1 as these are less resistant in the environment and easily killed by disinfectants. Pathogens to focus on are: C. difficile spores; norovirus and other non-enveloped viruses such as rotavirus; MRSA; Acinetobacter; VRE.

The remainder of the talk was around liquid disinfectants and wiping. He specifically highlighted the problem with disinfectants/wipes, which are effective at spreading contamination if they don’t actually kill pathogens. He outlined the results of one of his studies, where they tested a number of disinfectants with wiping action and found that all except one did not kill all pathogens and also did spread them to other surfaces.

Some key papers mentioned in the conference:

1- Zimlichman E, et al. Health Care-Associated Infections: A Meta-analysis of Costs and Financial Impact on the US Health Care System. JAMA Intern Med. 2013. Previously reviewed on the blog here.

2- Limb M. Variations in collecting data on central line infections make comparison of hospitals impossible, say researchers. BMJ. 2012 Sep 21;345:e6377.

3- Sattar SA, Maillard JY. The crucial role of wiping in decontamination of high-touch environmental surfaces: review of current status and directions for the future. Am J Infect Control. 2013 May;41(5 Suppl):S97-104.