Dogs are recognised to have the keenest of noses and have been used for detecting illicit drugs, early stage cancer and even C. difficile including an outbreak (possibly a cheaper option than PCR for screening – I should have used this in my debate with Jon). Now a new study finds that trained dogs can reliably detect significant bacteriuria.

Dogs are recognised to have the keenest of noses and have been used for detecting illicit drugs, early stage cancer and even C. difficile including an outbreak (possibly a cheaper option than PCR for screening – I should have used this in my debate with Jon). Now a new study finds that trained dogs can reliably detect significant bacteriuria.

screening

Should we start admission screening for C. difficile carriage? A Kiernan vs. Otter pro-con debate!

Both Martin and Jon wanted to post a blog about the same article, so thought we’d put our hands together, so to speak, into a pro-con format! We hope you find it useful.

Reconsidering the burden of CRE screening

Shortly after the PHE Toolkit was published, I blogged some crude sums to size the burden of CRE admission screening a la Toolkit. I’m pleased to report that colleagues at Imperial have done a much better job of this, published in a letter in the Journal of Infection. The study provides some evidence that the recommendation in the PHE CRE Toolkit to perform pre-emptive isolation of suspected carriers whilst obtaining three negative screens is simply not feasible. The team then compare an alternate strategy – of applying the Tookit triggers to admissions to high risk specialties only (intensive care, nephrology, cardiothoracic surgery, neurosurgery and oncology).

Is CRE lurking in nursing homes?

They say that things come in threes, so following hot on the heels of blogs about MRSA and other MDROs in nursing homes, I was struck by a recent outbreak report of CRE associated with nursing homes the Netherlands.

Following the admission of a patient from a Greek ICU, a nosocomial transmission of CRE (ST258 KPC K. pneumoniae) occurred. By the way, this occurred despite the hospital recognising the risk of CRE at the time of admission from the Greek ICU, perform an admission screening and implementing pre-emptive contact precautions. Then the index patient was transferred to a nursing home, where subsequent transmission occurred to four other patients.

How can we stop nursing homes nurturing MRSA?

There is an emerging feeling that we need to start spreading the focus of infection prevention and control beyond acute hospitals. There has always been a sense that standards of infection control outside of acute settings are, shall we say, “different” to acute hospitals (aka non-existent) so it’s great to see a study of an infection control intervention in nursing homes.

The study was a cluster randomised controlled trial of MRSA screening, decolonisation and enhanced environmental disinfection vs. standard precautions in 104 of 157 nursing homes in a Swiss region. The authors chose a rather unusual, pragmatic endpoint of the prevalence of MRSA colonisation after 12 months.

The English MRSA Miracle

If, in 2004, I’d told an MRSA expert that there would be around only 200 MRSA bloodstream infections (BSI) per quarter in England throughout 2014 they’d have laughed out loud. This is because, back in 2004, there were sometimes more than 100 MRSA BSI per month in some London hospitals (and around 2000 per quarter nationally), combined with a general perception that only around 30% of MRSA BSI are preventable. How wrong we were.

The reduction of MRSA BSI in England has been dramatic, with a reduction in the region of 90% achieved over a 5 year period. I was asked to speak on “The English MRSA Miracle” at a conference in Portugal today, so thought I’d share my thoughts. You can download my slides here.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly what is behind the ‘MRSA Miracle’ since quite a number of interventions occurred at more or less the same time (Figure 1):

Figure 1: National interventions aimed at reducing MRSA BSI.

Some have postulated that the national cleanyourhands campaign is responsible for the dramatic success. Indeed, there is a BMJ study that makes this case, showing that the national significant increase in the use of soap and water and alcohol gel correlated with the reduction in MRSA BSI. However, I contend that this can’t be the case because what has happened to the rate of MSSA and E. coli BSI over the same period? Nothing – no reduction whatsoever. If increases in hand hygiene compliance really do explain the reduction in MRSA BSI, then they should also reduce the rate of MSSA BSI (unless the increase in hand hygiene compliance only occurred after caring for MRSA patients, which seems unlikely).

There’s a more important epidemiological point here though. High-school tells us to change one variable at a time in science experiments. And yet in this case multiple variables were modified, so it’s not good science to try to pin the reduction to a single intervention, no matter how strong the correlation. (I should add that the authors of the BMJ study do qualify their findings to a degree: ‘National interventions for infection control undertaken in the context of a high profile political drive can reduce selected healthcare associated infections.’)

There has been much discussion about whether we should be investing in a universal or targeted approach to infection control. The failure of improved hand hygiene to make any impact on MSSA BSI suggests that targeted interventions are behind the reduction in MRSA. So what targeted interventions were implemented that may have contributed to the decline? MRSA reduction targets were introduced in 2004, a series of ‘high-impact interventions’ focused mainly on good line care in 2006 and revised national guidelines in 2006 (including targeted screening, isolation and decolonization) all contributed to a surge of interested infection control. Infection control teams doubled in size. Infection control training became part of mandatory induction programmes. And hospital chief executives began personally telephoning infection control to check “how many MRSA BSIs” they had left.

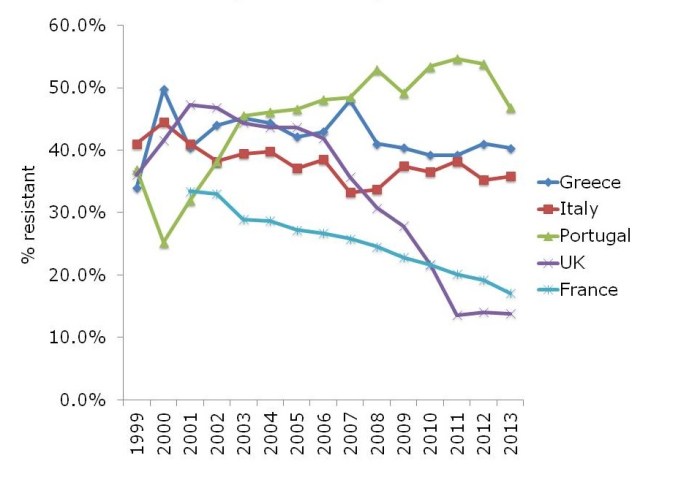

The ‘English MRSA Miracle’ has not been matched in most parts of Europe, except in France, which has had a rather more steady ‘MRSA Miracle’ of its own (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rate of methicillin-resistance in invasive S. aureus infections, from EARS-Net.

What is behind the failure of most European countries in controlling MRSA? The barriers are multifactorial, but include high levels of antibiotic use, a lack of single rooms for isolating patients, infection control staffing, and, of course, crippling national debt (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Barriers to infection prevention and control in Europe.

If the English MRSA Miracle is to be replicated across Europe, it will take concerted national initiatives to raise the profile of infection control, combined with considerable investment, which is challenging in these times of austerity.

Being bitten by antibiotic resistant CRAB hurts! (Acinetobacter that is.)

Guest bloggers Dr. Rossana Rosa and Dr. Silvia Munoz-Price (bios below) write…

In everyday practice of those of us who work in intensive care units, a scenario frequently arises: a patient has a surveillance culture growing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). While the ultimate course of action we take will be dictated by the patient’s clinical status, that surveillance culture, in the appropriate context, can provide us with valuable information.

For this study1, we looked at a cohort of patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit, and sought to identify the risk factors for CRAB infections. We found that patients who had surveillance cultures positive for CRAB had a hazard ratio of 16.3 for the development of clinical infections with this organism, compared to patient’s who remained negative on surveillance, even after adjusting for co-morbidities and antibiotic exposures. Since our results were obtained as part of a well-structured surveillance program, we know that colonization preceded infection. Unfortunately for some of our patients, the time from detection of colonization to development of clinical infections was a matter of days. With therapeutic options for the effective treatment of infections with CRAB limited to tigecycline and polymixins, the consequences of delaying therapy are often fatal. As described by Lee et al, a delay of 48 hour in the administration of adequate therapy for CRAB bacteremia can result in a 50% difference in mortality rate2.

Surveillance cultures are not perfect, and may not detect all colonized patients, but they can be valuable tools in the implementation of infection control strategies3, and as we found in our study, can also potentially serve to guide clinical decision that impact patient care and even survival.

Bio:

Dr. Silvia Munoz-Price (centre left) is an Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine at the Institute for Health and Society, Medical College of Wisconsin, currently serving as the Enterprise Epidemiologist for Froedert & the Medical College of Wisconsin. Dr. Rossana Rosa (centre right) is currently an Infectious Diseases fellow at Jackson Memorial Hospital-University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She hopes to continue developing her career in Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control.

References

- Latibeaudiere R, Rosa R, Laowansiri P, Arheart K, Namias N, Munoz-Price LS. Surveillance cultures growing Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Predict the Development of Clinical Infections: a Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. Oct 28 2014.

- Lee HY, Chen CL, Wu SR, Huang CW, Chiu CH. Risk factors and outcome analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii complex bacteremia in critical patients. Crit Care Med. May 2014;42(5):1081-1088.

- Munoz-Price LS, Quinn JP. Deconstructing the infection control bundles for the containment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. Aug 2013;26(4):378-387.

Image: Acinetobacter.

Universal vs. targeted interventions in infection prevention and control: the case for a targeted strategy

Today, I participated in a debate with Professor Ian Gould on universal vs. targeted interventions for infection prevention and control at Infection Prevention 2014. I was arguing for a targeted approach, and you can download my slides here, and you can listen to a recording of the talks here.

Universal interventions are appealing: they make no discrimination between patients, there’s a clear message for staff, and you have no way of knowing reliably who is colonized anyway! However, for me to get behind a universal intervention, it would have to demonstrate short-term, long-term and cost-effectiveness.

Before getting into the details of my argument, it is worth defining what we mean by ‘universal’ or ‘targeted’ interventions (see Table 1, below). It’s important to note that an intervention can be targeted either to an individual (e.g. chlorhexidine given to decolonize the skin of a patient known to be colonized with MRSA) or targeted to a population (e.g. chlorhexidine given to all patients in high risk settings, such as the ICU). Screening is an interesting one. It’s easy to mistake screening as a universal strategy when it’s applied to all patients (as is common in the NHS), but it’s fundamentally a targeted strategy to identify patients for an intervention (such as isolation and / or decolonization). A truly universal strategy has no need of screening.

Table 1: defining universal and targeted interventions.

Short-term effectiveness

Short-term effectiveness can be difficult to measure. What is the standard for demonstrating short-term effectiveness? Most common interventions lack accepted standards for demonstrating short-term effectiveness, and the results may well be different as setting and pathogen varies. However, there are some universal approaches that have effectively failed at the first hurdle and not demonstrated even short-term effectiveness. For example, ‘selective’ digestive decontamination has been applied to try to decolonize carriers of resistant Gram-negatives. Although this clearly has some impact, and reduces colonization, it seems to temporarily suppress the level of resistant bacteria in the gut flora, not decolonize the patient. Similarly, the use of universal gloves and gowns failed to meet the primary endpoint in a cluster randomized controlled study (the BUGG study).

Long-term effectiveness

A number of universal strategies that have demonstrated some level of short-term effectiveness fail in terms of long-term effectiveness due to the promotion of bacterial resistance (or reduced susceptibility). For example, selective digestive decontamination on a group of patients resulted in a sharp increase in gentamicin resistance, and perhaps more worryingly an increase in colistin resistance. Furthermore, a microbiomic analysis of a patient undergoing selective digestive decontamination identified a seven-fold increase in the abundance of aminoglycoside resistance genes in the ‘resistome’.

Another way in which universal strategies that are effective in the short-term may fail in the long-term is due to reliance on human beings to maintain compliance with protocols. This is relatively easy during studies, where staff have both support and scrutiny to drive performance. When the spotlight is off and they’re on their own, performance is less impressive. We can see this type of “reverse Hawthorne effect” in compliance with contact precautions, and in hand and environmental hygiene.

Cost effectiveness

Once a strategy has demonstrated both short-term and long-term effectiveness, it must demonstrate cost effectiveness before widespread adoption. Even if you disagree with me and consider screening to be a universal strategy for MRSA when applied to all patients at the time of admission, it has failed to demonstrate cost-effectiveness in almost all scenarios. Economic analysis using the standard threshold of £30,000 per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) has shown that screening all admissions for MRSA is not effective for teaching or acute hospitals at current, high or low prevalence. Universal screening was only cost-effective for specialist hospitals (the vast minority), and then only at some levels of MRSA prevalence. For this reason, the Department of Health is going to reverse its recommendation for universal screening of all hospital admissions.

Summary

I can’t think of a single universal intervention that has demonstrated short-term, long-term and cost effectiveness (see Table 2). Decolonization using chlorhexidine comes close, but almost all studies of this intervention have been performed in an ICU setting, where this intervention is applied to a targeted population. I would be uncomfortable about using chlorhexidine for daily bathing of all hospital patients due to the risk of promoting reduced bacterial susceptibility.

Table 2: short-term, long-term and cost-effectiveness of universal interventions.

Targeted interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing transmission, preserve the activity of our precious antimicrobial agents, require less modification of human behaviour, and are cheaper and less resource-intensive. So, on balance, I favour targeted interventions for infection prevention and control.

Isolation: the enemy of CRE

Pat Cattini (Matron / Lead Specialist Nurse Infection Prevention and Control, Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust) and I recently teamed up to present a webinar entitled: ‘Introduction to the identification and management of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE)’. You can download our slides here, and here’s the recording:

The webinar covered the following ground:

- Why the fuss?

- What are CRE?

- Who do we screen?

- How do we screen?

- What happens if someone is positive?

- Key questions

CRE represent a combination of anitibiotic resistance, mortality and potential for rapid spread, so we need to be proactive in our approach to the detection and management of carriers. We simply can’t afford for CRE to become established in the same way that MRSA did, so now is the time of opportunity to develop the most effective prevention strategy. The recently published Public Health England Toolkit is useful, but it’s a set of tools to help construct a local policy, not a one-size-fits-all CRE policy. We hope that this webinar will assit you in developing your local CRE policies and plans.

Oh, and look out for the Premiere of ‘ISOLATION: THE ENEMY OF CRE’ (a Pat Cattini film)…

Preventing HCAI: go long or go wide?

There seems to be a general movement away from targeted, pathogen-based precautions (principally screening and isolation) in the USA. This changing professional opinion was clear from the recent SHEA conference, where several leading experts gave what amounted to a collective justification for abandoning contact precautions for MRSA.

There seems to be a general movement away from targeted, pathogen-based precautions (principally screening and isolation) in the USA. This changing professional opinion was clear from the recent SHEA conference, where several leading experts gave what amounted to a collective justification for abandoning contact precautions for MRSA.

The update of the SHEA Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals is accompanied by a commentary from a group of leading US figures titled ‘Approaches for preventing HCAI: Go long or go wide’. In the commentary, the authors weigh the evidence and opinion for so-called ‘vertical’ (aka targeted) vs. ‘horizontal’ (aka universal) interventions (Table).

Table: Go long or go wide? Examples of targeted and universal interventions (adapted from Wenzel & Edmond, via Septimus et al.).

Table: Go long or go wide? Examples of targeted and universal interventions (adapted from Wenzel & Edmond, via Septimus et al.).

The commentary outlines the potential drawbacks of targeted approaches (such as fewer visits from healthcare workers and feelings of isolation), but doesn’t spend a lot of time discussing the potential drawbacks of universal approaches. For example, “isolation fatigue”, where a procedure loses its impact if it has to be applied to every patient. And then there’s the possibility of resistance when performing universal decolonization. This is particularly worrysome when using antibiotics, but could also be a problem when using biocides such as chlorhexidine.

I’m not ready to abandon pathogen-based targeted interventions just yet. Conceptually, it just does not make sense. If you have a patient with MRSA and a respiratory virus, chances are they will become a ‘super-spreader’. Those who favour universal approaches do make some provision for exceptional cases that really should be identified and isolated via a ‘syndromic’ approach to isolation: crudely, only isolate patients when they’re oozing. However, this syndromic approach would likely miss our ‘super-spreading’ patient, which may well result in an MRSA outbreak – that we could all do without.

Furthermore, if you have a patient who is colonized with CRE, are you brave enough to take no special precautions, as would be the case for a ‘universal only’ approach? The success of this strategy would depend on a high level of compliance with standard precautions such as hand hygiene and environmental cleaning and disinfection. Whilst sound in theory, this just doesn’t happen in the trenches; your facility is above average if your hand hygiene compliance rate is the right side of 40%. Whilst still not 100%, hand hygiene compliance is higher when patients are placed in isolation, most likely because there’s a stronger psychological trigger to comply with hand hygiene.

It’s important to note that targeted and universal approaches are by no means mutually exclusive. For example, on our ICU in London, we have been using universal chlorhexidine decolonization for a decade combined with targeted screening and isolation, and have seen a dramatic reduction in the spread of MRSA.

So, should we go long or go wide in the prevention of HCAI? The answer is both. We should optimize case for all patients, which means careful standard precations with liberal application of chlorhexidine and tight restriction of antibiotics. But we should also identify those with communicable pathogens and segregate them from others. In this regard, we have the weight of history on our side.

Image: Jeff Weese.