I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).

I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).

- Aug 19: CRE and friends: what’s the problem and how to detect them?

- Sept 16: Not all resistant Gram-negative bacteria are created equal: Enterobacteriaceae vs. non-fermenters

- Oct 7: Filling the gaps in the guidelines to control resistant Gram-negative bacteria

The webinar was attended by >200 participants from across the US. I tried to outline the three pronged threat of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative rods (especially CRE) in terms of high levels of antibiotic resistance, stark mortality (for invasive disease) and the potential for rapid spread (including the prospect of establishing a community reservoir). Then, I gave an overview of the US and European picture in terms of CRE prevalence. Finally, I discussed the diagnostic challenges and options.

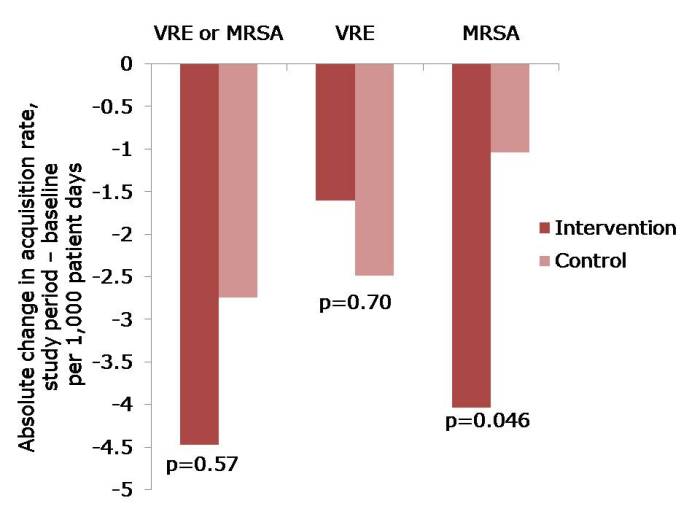

The most interesting part for me was the response to the questions that I threw out to the audience (see Figure below).

Figure: response to the questions from the 200 or so participants.

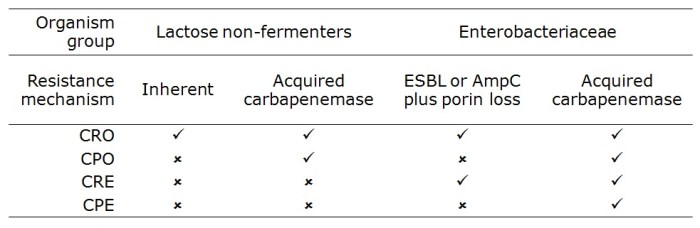

I was somewhat saddened but not especially surprised that the difference between CRE and CPE was not clear in the minds of most participants. I appreciate that this may be in part due to the fact that ‘CPE’ seems to be used more commonly in Europe than in the US. But this is an international problem, so we need to get our terminology straight in our globalised world.

It was encouraging to hear that most US hospitals have had no CRE, or only one or two cases. However, 11% of the participants see CRE regularly, with cases unconnected to outbreaks. This is a concern, and suggests that CRE has become established in these areas. Indeed, a recent study from 25 Southeastern US community hospitals reports a 5-fold increase in the prevalence of CRE since 2008, suggesting that CRE is becoming established in some parts of the US.

Most participants didn’t know which method was used by their clinical laboratory to detect CRE. I’m not sure whether or not this is a problem. You’d hope that laboratorians to know that they’re doing!

Q&A

The webinar included time for a Q&A from the audience, which covered the following:

- “How long to resistant Gram-negatives survive on surfaces?” This depends on which Gram-negative you’re talking about. Non-fermenters, especially Acinetobacter baumannnii, have remarkable survival properties measured in months and years. Enterobacteriaceae have a somewhat lower capacity to survive on dry surfaces, but it can still be measured in weeks and months, rather than hours and days.

- “How important is the environment in the transmission of resistant Gram-negatives?” Again, this depends on which Gram-negative you’re talking about. For A. baumannii the answer is probably “very important” whereas for the Enterobacteriaceae the answer is more like “quite important”.

- “What would you recommend for terminal disinfection following a case of CRE?” I would recommend the hospitals usual “deep clean” using either a bleach or hydrogen peroxide disinfectant, and consideration of using an automated room disinfection system. I would not be happy with a detergent or QAC clean; we can’t afford to leave an environmental reservoir that could put the next patient at risk.

- “Are antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria also likely to be resistant to disinfectants” There’s been a lot of discussion on this issue, but the short answer is no. I’d expect an antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolate to be as susceptible to disinfectants as a corresponding antibiotic-susceptible isolate.

- “Should patients with CRE be left to the end of surgical lists, and are is special instrument reprocessing required?” There is no need to implement special instrument reprocessing – follow your usual procedures here. Should CRE patients be left to the end of surgical lists? It would be prudent if possible, but don’t lose sleep over it.

- “Are any special decontamination measures necessary for endoscopes?” A number of outbreaks of CRE have been reported associated with endoscopy. However, usual endoscope reprocessing methods should be sufficient to deal with CRE, provided they are done correctly!

- “How do you lessen your chances of acquiring CRE?” Healthy individuals lack the risk factors for CRE infection (although CRE can occasionally cause infections in the community). Thus, the personal protective equipment (PPE) specified for contact precautions (gloves and gowns) combined with rigorous hand hygiene are sufficient to protect healthcare workers.

- “Are toilet seats in India safe?” What a question! I guess we’re talking about an organism with gastrointestinal carriage, so it’s probably that contamination of the toilet seat will occur. It may be prudent to clean or disinfect toilet seats in India before using them. Either that, or squat!

- “Can you expand on isolation protocols?” Firstly, ensure that patients infected or colonized with CRE are assigned a single room (not so relevant in the US, but important in healthcare elsewhere). Then, make sure you have appropriate policy and supply of PPE (principally gloves and gowns). Consider implementing ‘enhanced precautions’, including a restriction of mobile devices. Finally, consider cohorting patients and staff to the extent possible. You can read more about NIH’s approach to isolation here.

- “Can patients who are colonized with CRE be deisolated?” This is a tricky one, which is basically an evidence free zone and hence an area of controversy. Longitudinal studies show that carriage of CRE can persist for months or even years, so it makes sense to continue isolation for the duration of a hospitalization and not bother with repeated swabbing. At the time of readmission, it makes sense to take a swab to see whether colonization continues. If not, then it may be rational to deisolate them – perhaps after a confirmatory swab. I wish I could be more decisive here, but the evidence is scant.

Do please let me know if you have anything to add to this Q&A!