Sometimes waiting for research highlighting an issue that you know is a problem is like waiting for a bus.. Following on from my colleague @jonotter who last week posted about MRSA spread in nursing home settings, I was interested to read this new paper from the USA, published in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society. The study notes the high prevalence of Multi-Drug Resistant Organism (MDRO) carriage in nursing homes that was in excess of that in hospital settings and sought to determine any associations. The findings are interesting, if not surprising.

MRSA

How can we stop nursing homes nurturing MRSA?

There is an emerging feeling that we need to start spreading the focus of infection prevention and control beyond acute hospitals. There has always been a sense that standards of infection control outside of acute settings are, shall we say, “different” to acute hospitals (aka non-existent) so it’s great to see a study of an infection control intervention in nursing homes.

The study was a cluster randomised controlled trial of MRSA screening, decolonisation and enhanced environmental disinfection vs. standard precautions in 104 of 157 nursing homes in a Swiss region. The authors chose a rather unusual, pragmatic endpoint of the prevalence of MRSA colonisation after 12 months.

MRSA in Denmark

(from Statens Serum Institut, EPI-News, N023-2015)

‘The number of hospital-acquired cases observed in 2014 increased to 95 from 52 cases in 2013, but still comprise only a limited share of the total number of cases (3%). The number of MRSA cases of the CC398 type, which is closely associated with pigs, increased substantially from 643 cases in 2013 to 1,276 cases in 2014 and comprised 43% of the total number of cases. Community-acquired MRSA, i.e. in persons with no known contact to pigs, hospitals or nursing homes, comprised 946 cases in 2014, compared with 821 cases in 2013. In 478 of these cases (51%), there was known exposure to a person with MRSA, most frequently a member of the household (92%). In 56 cases, MRSA was isolated from blood, corresponding to 2.9% of all S. aureus bacteraemia cases, which is a substantial increase with respect to recent years, but the figure remains low compared with other European countries.’

And here I stop citing the report. For those interested in the complete report, please follow the link: MRSA Denmark.

The English MRSA Miracle

If, in 2004, I’d told an MRSA expert that there would be around only 200 MRSA bloodstream infections (BSI) per quarter in England throughout 2014 they’d have laughed out loud. This is because, back in 2004, there were sometimes more than 100 MRSA BSI per month in some London hospitals (and around 2000 per quarter nationally), combined with a general perception that only around 30% of MRSA BSI are preventable. How wrong we were.

The reduction of MRSA BSI in England has been dramatic, with a reduction in the region of 90% achieved over a 5 year period. I was asked to speak on “The English MRSA Miracle” at a conference in Portugal today, so thought I’d share my thoughts. You can download my slides here.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly what is behind the ‘MRSA Miracle’ since quite a number of interventions occurred at more or less the same time (Figure 1):

Figure 1: National interventions aimed at reducing MRSA BSI.

Some have postulated that the national cleanyourhands campaign is responsible for the dramatic success. Indeed, there is a BMJ study that makes this case, showing that the national significant increase in the use of soap and water and alcohol gel correlated with the reduction in MRSA BSI. However, I contend that this can’t be the case because what has happened to the rate of MSSA and E. coli BSI over the same period? Nothing – no reduction whatsoever. If increases in hand hygiene compliance really do explain the reduction in MRSA BSI, then they should also reduce the rate of MSSA BSI (unless the increase in hand hygiene compliance only occurred after caring for MRSA patients, which seems unlikely).

There’s a more important epidemiological point here though. High-school tells us to change one variable at a time in science experiments. And yet in this case multiple variables were modified, so it’s not good science to try to pin the reduction to a single intervention, no matter how strong the correlation. (I should add that the authors of the BMJ study do qualify their findings to a degree: ‘National interventions for infection control undertaken in the context of a high profile political drive can reduce selected healthcare associated infections.’)

There has been much discussion about whether we should be investing in a universal or targeted approach to infection control. The failure of improved hand hygiene to make any impact on MSSA BSI suggests that targeted interventions are behind the reduction in MRSA. So what targeted interventions were implemented that may have contributed to the decline? MRSA reduction targets were introduced in 2004, a series of ‘high-impact interventions’ focused mainly on good line care in 2006 and revised national guidelines in 2006 (including targeted screening, isolation and decolonization) all contributed to a surge of interested infection control. Infection control teams doubled in size. Infection control training became part of mandatory induction programmes. And hospital chief executives began personally telephoning infection control to check “how many MRSA BSIs” they had left.

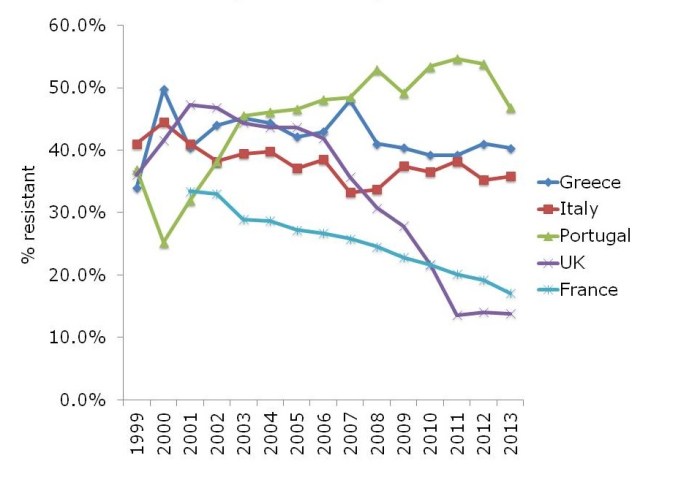

The ‘English MRSA Miracle’ has not been matched in most parts of Europe, except in France, which has had a rather more steady ‘MRSA Miracle’ of its own (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rate of methicillin-resistance in invasive S. aureus infections, from EARS-Net.

What is behind the failure of most European countries in controlling MRSA? The barriers are multifactorial, but include high levels of antibiotic use, a lack of single rooms for isolating patients, infection control staffing, and, of course, crippling national debt (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Barriers to infection prevention and control in Europe.

If the English MRSA Miracle is to be replicated across Europe, it will take concerted national initiatives to raise the profile of infection control, combined with considerable investment, which is challenging in these times of austerity.

ECDC data shows progressive, depressing increase in antibiotic resistance in Europe

The ECDC recently released their 2013 report, which includes 2013 data. The data are on the whole fairly depressing for more parts of Europe, with high and increasing rates of resistance to important antibiotics in common bacteria. So it was not surprising to see ECDC issue a corresponding press release focusing on worrying resistance to last-line antibiotics.

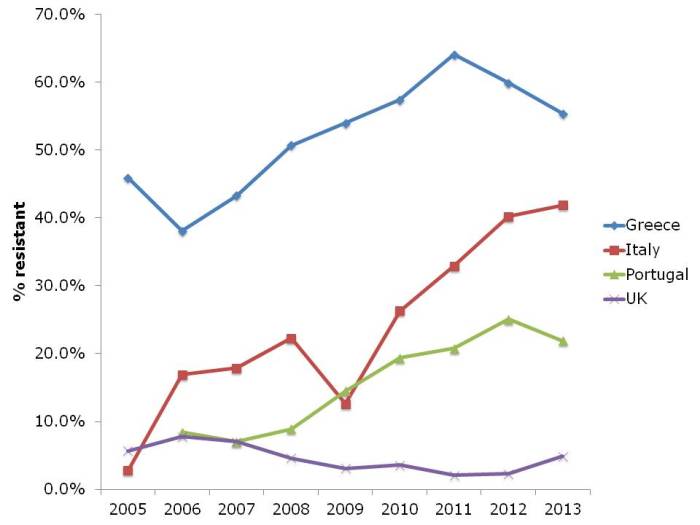

I’ve chosen a few illustrative countries from this useful interactive database. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae (i.e. CRE) is one of the most concerning challenges facing us right now. So it’s not good to see continued high rates of carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae in Greece, and the seemingly inexorable increase in Italy (Figure 1). It’s worth noting that these are invasive isolates, the majority of which would be bloodstream infections. And the mortality rate for a CRE bloodstream infection is around 50%…

Figure 1: Susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates to carbapenems

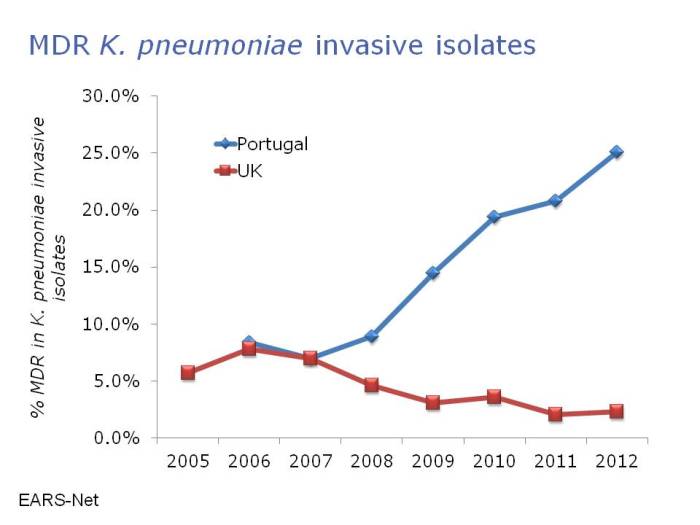

In some ways, the steady increase in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae from many parts of Europe, illustrated in Figure 2, is even more concerning than the sharp increases in CRE in some parts of Europe. If you draw a mental trend line for Italy and Portugal, it doesn’t look good.

Figure 2: Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates (resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides)

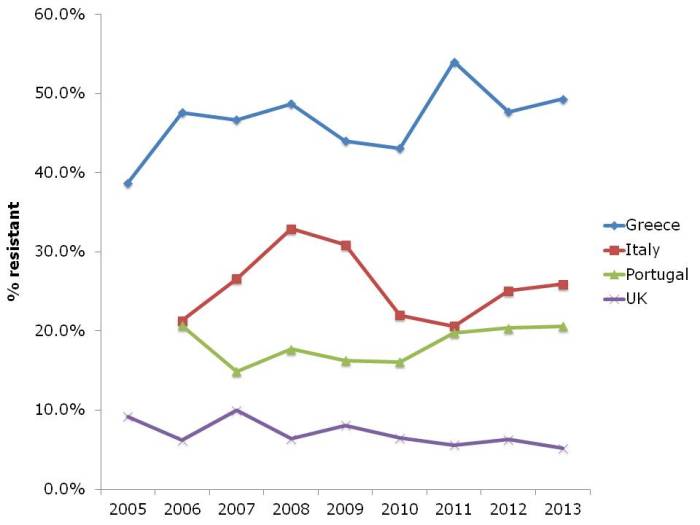

The picture for P. aeruginosa (and I suspect the other non-fermenters like A. baumannii, which isn’t included in EARS-Net) in terms of carbapenem resistance is different to the Enterobacteriaceae (Figure 3). Rates are high in Greece, intermediate in Italy and Portugal, and low in the UK. But the trend is stable.

Figure 3: Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasive isolates to carbapenems

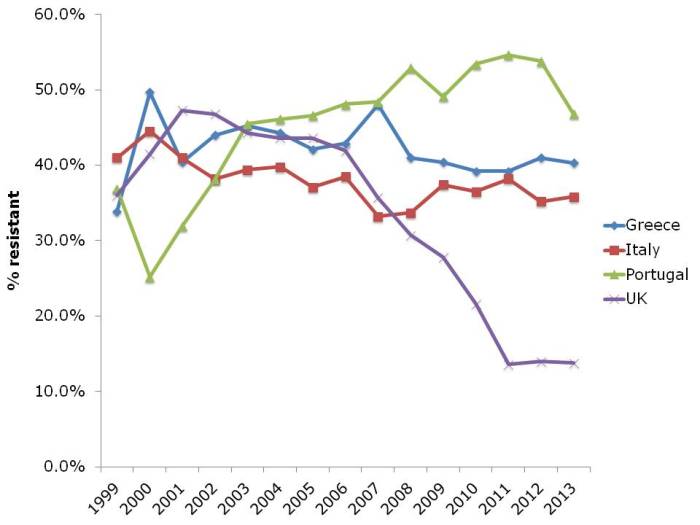

And let’s not forget about MRSA (Figure 4). The UK and some other European countries have done a tremendous job in reducing the transmission of MRSA. This has had an interesting and somewhat unexpected effect on the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus, which has also reduced considerably. I suspect this is a consequence of interrupting the transmission of MRSA, but failing to prevent the spread of MSSA. Put another way, if MRSA and MSSA fell in tandem, the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus would remain constant. The impressive reductions of MRSA reported in the UK have not been replicated everywhere in Europe. Portugal in particular increased from less than the UK in the early 2000s to more than the UK today. There is some evidence that the national campaign in Portugal to reduce healthcare-associated MRSA is making some impact, with a notable reduction in MRSA rate in 2013.

Figure 4: Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus invasive isolates to methicillin (i.e. MRSA rate)

In summary, it’s not all doom and gloom. The reductions in MRSA in the UK and elsewhere show that reducing the transmission of these antibiotic resistant bacteria can be done. But it takes considerable investment and national focus. Without this, it’s difficult to see the trends in antibiotic resistance, including to last-line agents, continuing to increase in some parts of Europe.

Reflections from HIS 2014, Part I: Updates on C. difficile, norovirus and other HCAI pathogens

The 2014 Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) Conference was in Lyon, France, and combined with SFH2 (The French Society for Hospital Hygiene). Congratulations to all involved (especially Martin Kiernan and Prof Hilary Humphreys) for such a stimulating programme, and enjoyable conference. The abstracts from the oral presentations can be downloaded here, and the posters here. I plan to share some of my reflections on key conference themes over the next few days:

- Part I: Updates on C. difficile, norovirus and other HCAI pathogens

- Part II: Dealing with the contaminated environment

- Part III: Education, communication, and antibiotic resistance

- ‘What’s trending in the infection prevention and control literature?

HIS 2012 -> HIS 2014’ - ‘HIS Poster Round: Dealing with contaminated hands, surfaces, water and medical devices.’

Prof Wing-Hong Seto – Airborne transmission and precautions – facts and myths

Prof Seto’s energy and enthusiasm lit up the stage, just like a few years ago in Geneva for ICPIC. Prof Seto spent his lecture convincingly debunking the idea that airborne transmission of respiratory viruses is common, notwithstanding some data that, prima facie, suggests this. Only very few pathogens require obligate airborne transmission (e.g. TB); some have preferential airborne transmission (e.g. measles); and some have potential airborne transmission (respiratory viruses). There is some evidence that respiratory viruses such as influenza can be transmitted via the airborne route, but the most important route of transmission will depend on context. One important point is that studies demonstrating airborne “transmission” using PCR rather than viral culture as an endpoint, or using artificial aerosol generation should not be taken as definitive evidence of airborne transmission. Prof Seto’s view is that medical masks are sufficient to prevent the transmission of respiratory viruses, as demonstrated by his own work during SARS. Finally, we can forget the requirement for negative pressure isolation rooms: open doors and windows yields a whopping 45 air changes per hour!

Prof Mark Wilcox – Is Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) underestimated due to inappropriate testing algorithms?

Prof Wilcox began by reporting an unusual epidemic: “PCRitis”, which can cloud rather than clarify accurate diagnosis of CDI. Perhaps the most important point made by Prof Wilcox is that the ultimate “gold standard” for CDI should be clinical, and not laboratory based. Prof Wilcox spent most of his time reflecting on the recent multicentre European study of CDI underdiagnosis in Europe. There are some real shockers in here: the reported rate of CDI in Romania was 4 cases per 1000 patient days vs. closer to 100 per 1000 patient days when samples from the same patients were tested in the reference lab. This is no surprise in a sense because only 2/5 local laboratories were using optimal methods. However, even in the UK where around 80% of local labs are using optimal methods, around 2-fold more cases were identified in the reference vs. the local laboratory. Clearly, if we’re going to have a hope of controlling the spread of C. difficile in Europe, laboratory diagnosis needs to improve.

Norovirus

Norovirus is especially topical in the UK given the recent PHE announcement about unusually high rates of norovirus in the NHS. The prolific Dr Ben Lopman (CDC) began by explaining the ‘image problem’ that norovirus has in US hospitals, where it is considered an uncommon cause of gastroenteritis. In fact, a systematic review found that norovirus cases around 20% of acute gastroenteritis. However, I would say it’s just not possible to get an accurate assessment of how common norovirus is on a population level due to chronic under-reporting. When we had an outbreak of ”norovirus” in the Otter household, the last thing we felt like doing was submitting a specimen, and I suspect we are not alone in this! Although norovirus is usually mild and self-limiting, it is by no means benign: one Lopman study suggested that it is responsible for 20% of deaths due to gastroenteritis not caused by C. difficile in those ages >65. And then there’s the infection control challenges. Due to the exquisitely low infectious dose, 2g of stool from an infected individual is enough to infect the entire human population! Plus, it is shed in high titre, stable in the environment, and resistant to many disinfectants. Rather depressingly, it seems that effective interventions to control norovirus teeter around the cost-effectiveness threshold. More optimistically though, prospects for vaccines look promising.

Prof Marion Koopmans then described the huge diversity within the “norovirus” family, spanning more phylogenic space than many single species occupy. For chapter and verse on nomenclature, see Norovirus Net. It’s difficult to know what works to control norovirus due to dynamic outbreak settings combined with multiple interventions. One key aspect for control is understanding shedding profiles of infected, recovered and asymptomatic individuals. Whilst all can shed norovirus, much like Ebola, those who are symptomatic are by far the highest risk for transmission. Finally, our inability to culture norovirus in the lab has been an important barrier to understanding the virus; a recent study (in Science no less) suggests that a working lab model for culturing norovirus may be just around the corner.

Dr Lennie Derde – Rapid diagnostics to control spread of MDR bacteria at ICU

Given the turnaround times of conventional culture (24 hours to preliminary results – at best), rapid PCR-based diagnostics make sense in principle. But do they work in practice? There is some evidence that rapid diagnostics may work to reduce MRSA transmission, although other studies suggest that they don’t make a difference. In order to put rapid diagnostics to the test Dr Derde et al. ran the impressive MOSAR study. This study suggest that screening and isolation by conventional or rapid methods does not help to prevent the transmission of MDROs in the ICU, but I don’t think we should take that away from this study, not least due to the fact that many units were already doing screening and isolation during the baseline period!

New insights from whole geneome sequencing (WGS)

WGS is trendy and trending in the infection prevention and control sphere. Prof Derrick Crook gave an engaging overview of the impact that WGS has made. It’s analogous to the manual compilation and drawing of maps to GPS; you wouldn’t dream of drawing a map by hand now that GPS is available! Desktop 15 minute WGS technology will be a reality in a few years, and it will turn our little world upside down. The major limiting step, however, is that mathematics, computer science and computational biology are foreign to most of us. And we are foreign to most of them! But, these issues are worth solving because the WGS carrot is huge, offering to add new insight into our understanding of the epidemiology of pathogens associated with HCAI. For example, Prof Crook WGS study on C. difficile suggests that transmission from symptomatic cases is much less common than you’d expect. So if the C. difficile is not coming from symptomatic cases, where is it coming from? Contact with animals and neonates in the community are plausible sources However, I was surprised that Prof Crook didn’t mention the large burden of asymptomatic carriage of toxigenic C. difficile, which must be a substantial source for cross-transmission in hospitals.

WGS has yielded similar insight into the epidemiology of TB and MRSA, outlined by Drs Timothy Walker and Ewan Harrison, respectively. One challenging idea from Dr Harrison is how much of the “diversity cloud” that exists within an individual is transferred during a transmission event? Finally, WGS can turn a ‘plate of spaghetti’ of epidemiological links to a clear transmission map, as was the case during a CRE outbreak at NIH in the USA.

Look out for some more reflections from HIS posted over the next few days…

A postcard from Portugal: “Some days we don’t have any needles on the ICU”

Most of us know that Portugal is facing a dual threat: high rates of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and financial difficulties. This results in a vicious cycle: there’s no money to address antibiotic resistance, so transmission continues unabated and the antibiotic resistance problem gets worse. You can understand the dilemma from the hospital administrators’ viewpoint: I met an intensivist who confessed that “some days we don’t have any needles”. In this situation, is it better to buy some needles or invest in another infection preventionist?

I recently attended a national infection control meeting in Portugal, where I participated in a forum on “International experiences with HCAI”. You can download my slides here.

MRSA first emerged as a problem in the 1980s in Europe. It became a major problem in many European countries in the 1990s and 2000s so that recent data from ECDC shows high rates of meticillin resistance in S. aureus invasive isolates, especially in some southern European countries; the contrast between the rate of MRSA in the UK and Portugal is stark. In the early 2000s, the rate of MRSA was higher in the UK than in Portugal whereas now, it is much lower in the UK (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Rates of meticillin-resistance in invasive S. aureus in the UK and Portugal. Data from EARS-Net.

Greece, Italy and Portugal are especially affected, with 25 to >50% of invasive S. aureus isolates resistant to methicillin. In the UK, a national strategy has yielded a dramatic reduction in the number of MRSA bloodstream isolates reported to the government in a mandatory reporting scheme (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dramatic reductions in MRSA bacteraemia in England. But what has made the difference?

Since the national intervention in England was multifactorial, it is not clear what made the most impact, and it seems likely that more than one intervention contributed to the decline. Interventions included increased attention to intravenous line care, cleaning and disinfection of the environment, improved diagnostics (including the introduction of chromeagar and rapid PCR) and a national hand hygiene campaign. Perhaps the single most important intervention was the introduction of MRSA reduction targets, which were very controversial at the time, but put the issue of MRSA higher on the priority list for the hospital administration.

And this issue is not restricted to MRSA. In fact, the threat of the resistant Gram-negatives is even greater than MRSA in many ways. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae are rare currently in Portugal, accounting for 1-5% of invasive K. pneumoniae isolates. However, you get the feeling that it’s only a matter of time: carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii are now endemic on many Portugese ICUs, and carbapenem use in Portugal is some of the highest in Europe, with >45% of patients on an antibiotic and >5% of patients on a carbapenem according to the ECDC point prevalence survey. Indeed, there has been a disturbing increase in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae in Portugal in recent years (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Disturbing emergence of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Portugal. Data from EARS-Net.

The reason for these differences between the UK and Portugal is not clear, but may include infection control staffing, antibiotic usage and lower prioritisation by hospitals. Some progress is being made in Portugal with the recent launch of a national strategy to control healthcare-associated infection. However, the financial climate and somewhat fragmented healthcare system (compared with the NHS) will make implementation challenging. But at least it’s a start.

Image: Portugal stamp.

Are contaminated hands more important than contaminated surfaces?

Cast your minds back to the 2010 HIS conference in Liverpool and Drs Stephanie Dancer and Stephan Harbarth debating the relative importance of contaminated hands vs. surfaces in the transmission of MDROs. I don’t remember the details of the debate, but I do remember the surprising lack of evidence on both sides. Back then, we had no real way to quantify the contribution of the environment to the transmission of MDROs, or to measure the relative importance of contaminated hands vs surfaces. The evidence has evolved to the extent that a group of US researchers have published a paper modeling the relative contribution of contaminated hands vs surfaces to the transmission of MDROs. I like the paper very much, and the authors should be congratulated for breaking new ground in understanding transmission routes of MDROs.

The model simulates patient-to-patient transmission in a 20-bed ICU. The values of the parameters that were used to build the model were sensible on the whole, although baseline hand hygiene compliance was set at 57-85% (depending on staff type and whether at room entry or exit), which seems rather generous when baseline environmental cleaning compliance was set at 40%. Also, the increased risk from the prior room occupant for MRSA and VRE was set at 1.4 (odds ratio) for both, whereas it probably should be higher for VRE (at least >2) based on a number of studies.

100 simulations were run for each pathogen, evaluating the impact of step-wise changes in hand hygiene or terminal cleaning compliance. The key finding is that improvements in hand hygiene compliance are more or less twice as effective in preventing the transmission of MDR A. baumannii, MRSA or VRE, i.e. a 20% improvement in terminal cleaning is required to ‘match’ a 10% improvement in hand hygiene compliance. Also, the relationship between improved terminal cleaning and transmission is more or less linear, whereas the relationship with hand hygiene shows relatively more impact from lower levels of hand hygiene compliance (see Figure, below). Thus, the line for improving hand hygiene or terminal cleaning would intercept and indeed cross over at around 40 or 50% improvement. The implication here is that hand hygiene is more important at low levels of compliance, whereas terminal cleaning is more important at high levels of compliance (although don’t forget the difference in the baseline compliance ‘setpoint’.

Figure. The impact of percentage improvement in hand hygiene or terminal cleaning on the transmission of MDROs. Dotted line represents my not-very-scientific extrapolation from eyeballing the data.

Figure. The impact of percentage improvement in hand hygiene or terminal cleaning on the transmission of MDROs. Dotted line represents my not-very-scientific extrapolation from eyeballing the data.

The study raises some important issues for discussion:

- It had not struck me before that the level of compliance with hand hygiene and environmental cleaning are nearly identical, on average, with only around 40% of hand hygiene opportunities met and 40% of environmental surfaces cleaned if human beings are left to their own devices. Both of these figures can be improved considerably with concerted effort, but the sustainability of these improvements without continued effort is rather disappointing.

- The models address MRSA, VRE and MDR A. baumannii transmission. It’s a little strange that C. difficile was not included, since most consider this to be the ‘most environmental’ hospital pathogen.

- The study only modeled the impact of terminal cleaning, whereas daily cleaning seems likely to also be an important factor (which is acknowledged as a limitation in the discussion). This seems especially important in light of data that touching a contaminated surface carries approximately the same risk of hand contamination as touching an infected or colonized patient.

- I am not certain that this assumption makes logical sense: ‘thoroughness of cleaning of 40% implies that, given a single cleaning opportunity, there is a 40% probability that the room will be cleaned sufficiently well to remove all additional risk for the next admitted patient’. This would be true if cleaning was performed to perfection 4 times out of 10, whereas it is actually performed with 40% efficacy 10 times out of ten! To this end, it would be interesting to insert the various automated room disinfection systems into the model to evaluate and compare their impact. Indeed, hydrogen peroxide vapour has been shown to mitigate and perhaps even reverse the increased risk from the prior room occupant (for VRE at least).

- In the introduction, the authors comment that ‘A randomized trial comparing improvements in hand hygiene and environmental cleaning would be unethical and infeasible.’ I see what they’re saying here, in that it would be unethical by modern standards to investigate the impact of no hand hygiene or no environmental cleaning (although this has been done for hand hygiene), but it would be useful, feasible and ethical to perform a cluster RCT of improving hand hygiene and environmental cleaning. It would look something like the classic Hayden et al VRE study, but with an RCT design.

- How useful is mathematical modeling in informing decisions about infection prevention and control practices? This is not the first mathematical model to consider the role of the environment. For example, researchers have used models to evaluate the relative importance of various transmission routes including fomites for influenza. But a model is only as good as the accuracy of its parameters.

- Does this study help us to decide whether to invest in increasing hand hygiene or terminal cleaning? To an extent yes. If you have awful compliance with both hand hygiene and terminal cleaning at your facility, this study suggests that improving hand hygiene compliance will yield more improvement than improving terminal cleaning (for A. baumannii, MRSA and VRE at least). However, if you have high levels of compliance with hand hygiene and terminal cleaning, then improving terminal cleaning will yield more.

In general, this study adds more evidence to the status quo that hand hygiene is the single most effective intervention in preventing the transmission of HCAI. However, in a sense, the hands of healthcare workers can be seen as high mobile surfaces that are often contaminated with MDROs and rarely disinfected when they should be!

What works to control antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the ICU? A two-for-the-price-of-one study

Not content with a single well-planned study to provide information on what works to control multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) in the ICU, the MOSAR study group published an interrupted time series and a cluster randomized trial of various interventions in the Lancet ID. This makes the study rather complex to read and follow, but there are a number of important findings.

Interrupted time series – ‘hygiene’ intervention (chlorhexidine and hand hygiene)

Following a 6-month pre-intervention period, a 6-month interrupted time series of a ‘hygiene’ intervention (universal chlorhexidine bathing combined with hand-hygiene improvement) was performed. The key outcomes were twofold: whether there was a change in trend during each phase, and whether there was a step-change between the phases. The hygiene intervention effected a trend change reduction in all MDROs combined and MRSA individually, but not in VRE or ESBLs (Table). However, there was no step-change compared with the baseline period.

Table: Summary of reduced acquisition of all MDROs combined, or MRSA, VRE and ESBLs individually.

Cluster RCT – screening and isolation

In the 12-month cluster RCT of screening and isolation, the 13 ICUs in 8 European countries were randomized to either rapid screening (PCR for MRSA and VRE plus chromogenic media for ESBL-Enterobacteriaceae) or conventional screening (chromogenic media for MRSA and VRE only). When analysed together, the introduction of rapid or conventional screening was not associated with a trend or step-change reduction in the acquisition of MDROs (Table). In fact, there was an increase in the trend of MRSA acquisition. When comparing rapid with conventional screening, rapid screening was associated with a step-change increase in all MDROs and ESBLs.

Discussion

- The study suggests, prima facie, not to bother with screening and isolation. Indeed, the authors conclude: “In the context of a sustained high level of compliance to hand hygiene and chlorhexidine bathing, screening and isolation of carriers do not reduce acquisition rates of multidrug-resistant bacteria, whether or not screening is done with rapid testing or conventional testing”. However, the major limitation here is that many of the ICUs were already doing screening and isolation during the baseline and hygiene intervention phases! I checked the manuscript carefully (including the supplemental material) to determine exactly how many units were, but it is not disclosed. To make this conclusion, surely the cluster RCT should have been ‘no screening and isolation’ vs. ‘screening and isolation’.

- The increasing trend of MRSA associated with screening and isolation by either method, and step-change increases in all MDROs and ESBLs associated with rapid screening are difficult to interpret. Is an increase in acquisition due to screening and isolation plausible? Can more rapid detection of carriers really increase transmission (the turnaround time was 24 hours for rapid screening, and 48 hours for chromogenic screening)? The rapid screening arm also included chromogenic screening for ESBLs, whereas the conventional screening arm did not, so perhaps this apparent increase in acquisition is due to improved case ascertainment somehow?

- Looking at the supplemental material, a single hospital seemed to contribute the majority of MRSA, with an increasing trend in the baseline period, and a sharp decrease during the hygiene intervention. There’s a suspicion, therefore, that an outbreak in a single ICU influenced the whole study in terms of MRSA. Similarly, a single hospital had a sharp increase in the ESBL rate throughout the screening intervention period, which may explain, to a degree, the increasing trend of ESBL in the rapid screening arm.

- There was an evaluation of length of stay throughout the study phases, with a significant decrease during the hygiene intervention (26%), a significant increase during the rapid screening intervention, and no significant change during the conventional screening intervention. It seems likely that improved sensitivity of rapid screening identified more colonized patients who are more difficult to step down, resulting in an overall increase in length of stay.

- The carriage of qacA and qacB was compared in the baseline and hygiene intervention phase, finding no difference in carriage rate (around 10% for both). This does not match our experience in London, where carriage rates of qacA increased when we introduced universal chlorhexidine bathing. However, this was restricted to a single clone; the acquisition of genes associated with reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine seems to be clone-specific.

- ICUs varied from open plan to 100% single rooms. Whilst the average proportion of patients in single rooms (15-22%) exceeded the average requirement of patients requiring isolation (around 10%), there was no measure of unit-level variation of single room usage. Since the study was analysed by cluster, the lack of single rooms on some units could have been more important than would appear from looking at the overall average. Put another way, a 100% open plan unit would have been forced to isolate all carriers on the open bay, and vice versa for a 100% single room unit.

- The impact of the various interventions was moderate, even though a ‘high’ MRDO rate was necessary for enrollment (MRSA bacteraemia rate >10%, VRE bacteraemia rate >5%, or ESBL bacteraemia rate >10%). Would the impact of screening and isolation be different on a unit with a lower rate of MDROs? It’s difficult to tell.

- Some of the microbiology is quite interesting: 8% of MRSA were not MRSA and 49% of VRE were not VRE! Also, 29% of the ESBLs were resistant to carbapenems (although it’s not clear how many of these were carbapenemase producers).

In summary, this is an excellent and ambitious study. The lack of impact on ESBL transmission in particular is disappointing, and may lead towards more frequent endogenous transmission for this group. The results do indicate screening and isolation did little to control MDRO transmission in units with improved hand hygiene combined with universal chlorhexidine. However, we need a ‘no screening and isolation’ vs. ‘screening and isolation’ cluster RCT before we ditch screening and isolation.

IFIC 2013 Conference Report

The 13th International Federation of Infection Control (IFIC) meeting took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina in October 2013. A colleague who attended sent me some notes from the meeting, which I was not able to attend. I found the notes useful, so thought I’d share them (albeit a little late)!

Pro-Con debates

The first was on government regulations in infection control. The Pro delivered by H Baguio from Uruguay and Con by M Borg from Malta. H Baguio gave examples where government regulations have had impact on infection rates, citing the case of MRSA in the UK and reductions in bacteraemia, UTI and KPC prevalence after governmental regulation and auditing introduced in Uruguay. M Borg gave examples were governmental interventions did not improve the situation: for example, a 5x increase in the cost of medical waste disposal due to an insistence on considering it hazardous, when much could be considered non-hazardous. Also, there is a suggestion that since CLABSIs became non-refundable by the US government, many hospitals have started using peripheral lines over central lines to avoid financial loss. Another possible consequence is a less active attempt to detect infections in US hospitals, and a reticence to admit high-risk patients to avoid infection. However, in general the debate was not really pro-con as both admitted that some sort of government regulation is needed but they were not the only solution. This was reflected in the final results: 50% pro and 50% con.

The second debate was about universal vs. targeted MRSA screening. T. Boswell was arguing for universal screening, while E Lingaas of Norway was for targeted. There were good arguments from both sides but the vote suggested a swing towards targeted screening. I think the debate would have been more interesting if it as about universal screening for all pathogens of interests such as the emerging MDR Gram-negative bacteria. Whether you choose universal or targeted screening will depend on your country and healthcare setting. In countries with high carriage prevalence, universal screening will be more beneficial, especially when using quick and cheap diagnostic tests. For countries with low prevalence, targeting screening probably makes more sense. However, choose your targeted screening approach carefully: I performed a study recently where we found that reverting to our targeted screening approach would miss around 50% of carriers!

Selected talks

Stella Maimone (Buenos Aires, Argentina): “Infection control: the other side of the moon”

Stella was the first registered infection control nurse in Argentina. Most IC nurses in Argentina have been trained by her. She gave a general talk on IC in Latin America (LA) based mainly on the differences between Latin America and developed countries in IC. She noted that most LA countries ministries of health have some sort of infection surveillance systems including in Argentina. However, the data are not publicly available (at least in Argentina) which is a major difference between LA vs. USA and Europe.

Although LA countries are aware of the cost of HAIs, they have limited resources and it is not possible to reproduce the same IC policies that are implemented in US and UK (e.g. CDC guidelines) in LA. The reasons for that are: limited resources, different culture, LA people don’t like to be controlled (i.e. governmental regulations will have limited effect), and LA people think short term hence IC policies aimed at results in the distant future will not be adopted.

Hence for effective IC policies in LA, the limited resources of the countries/hospitals, the wider culture of society, and the ‘micro culture’ of the healthcare community must be taken into consideration.

Maria Clara Padoveze (University of Sao Paulo, Brazil): “Help! An outbreak!”

This was an interactive session with Q & A throughout. The informative talk covered outbreak definition and detection, but did not address outbreak control and infection control interventions in detail, which was a shame. Maria highlighted a useful website for performing quick literature reviews on various outbreaks from round the world: www.outbreak-database.com. This gives you an up-to-date (ish) report of outbreaks from around the world. If you register (free) you can access advance search where you can search per country for example.

Celeste Lucero (Argentina): “MDROs: a new world war”

This helpful overview began with an overview of how organisms acquire multidrug resistance. Celeste mentioned the WHONET-Argentina, which is a WHO Collaborating Centre for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in the country. Celeste offered a few examples including the CTXM-2, which is endemic in Argentina, and the emergence of CTXM-15 and OXA-163. She also mentioned that many Acinetobacter baumannii are now only treatable by Tigicycline and Colistin, and that rates of KPC have been increasing since 2010. To compound matters, Argentina had its first reported NDM-1 in 2013. I left the talk without a clear picture of prevalence of MDROs in Argentia, which may reflect the paucity of accurate epi data.

Martin Kiernan (UK): “Taking infection prevention to the next level”

Martin gave a talk on the UK experience in IC, citing examples of the impressive reductions achieved in the UK for MRSA and C. difficile, and the various interventions to achieve these reductions. He mentioned that the problem now is MDR Gram-negatives such as E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. His talk focused on how to change the IC culture in a hospital, including getting everyone engaged.

Syed Sattar (University of Ottawa, Canada): “The role of high-touch environmental surfaces in the spread of HAI: strategies to minimize the risks”

The talk began by outlining the factors that determine the risk of transmission from an environmental surfaces: probability of contamination; ability of pathogen to survive on the surface; transmission potential (e.g. porous surfaces are poor at transmitting pathogens, hence focus more on hard surfaces); location and frequency of direct contact with the surface (e.g. via hands or mucous membranes). He then went to define which pathogens to focus on. He warned not to focus on the high profile pathogens or the “pathogen of the month” such as HIV or H1N1 as these are less resistant in the environment and easily killed by disinfectants. Pathogens to focus on are: C. difficile spores; norovirus and other non-enveloped viruses such as rotavirus; MRSA; Acinetobacter; VRE.

The remainder of the talk was around liquid disinfectants and wiping. He specifically highlighted the problem with disinfectants/wipes, which are effective at spreading contamination if they don’t actually kill pathogens. He outlined the results of one of his studies, where they tested a number of disinfectants with wiping action and found that all except one did not kill all pathogens and also did spread them to other surfaces.

Some key papers mentioned in the conference:

1- Zimlichman E, et al. Health Care-Associated Infections: A Meta-analysis of Costs and Financial Impact on the US Health Care System. JAMA Intern Med. 2013. Previously reviewed on the blog here.