Drs Tara Palmore and David Henderson have written an engaging ‘view from the trenches’ in CID reflecting on their efforts to control an ongoing outbreak of CRE at the NIH Clinical Center, beginning in 2011.

The review outlines their interventions, including:

- aggressive active surveillance (including regular house-wide surveys);

- rapid identification and characterization of resistant organisms and resistance mechanisms (a mixture of conventional culture-based microbiology, mass-spec and mass spec);

- whole-genome sequencing of outbreak isolates (which allowed the identified of counterintuitive transmission patterns);

- enhanced contact precautions for all infected or colonized patients (patients only to leave room for medical reasons, visitors to wear gloves and gowns, staff not to touch personal electronic devices, preferable use of single-use equipment and enhanced terminal disinfection);

- geographic and personnel cohorting;

- daily chlorhexidine gluconate baths;

- dedicating equipment for cohorted patients and aggressive decontamination of equipment that had to be reused on uncohorted patients;

- monitoring adherence to infection control precautions, including unwavering attention to adherence to appropriate hand hygiene procedures (included the use of observing ‘enforcers’ to make sure staff complied with the basics);

- enhanced environmental decontamination (including double bleach wipe daily disinfection, hydrogen peroxide vapor for terminal disinfection and careful management of drains);

- engagement of all stakeholders involved in care of at-risk patients;

- and detailed, frequent communication with hospital staff about issues relating to the outbreak.

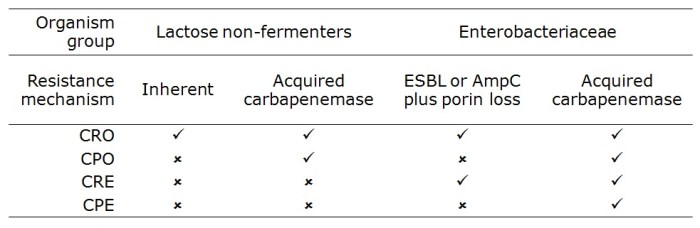

The authors discuss the problem of determining which of these interventions worked, since they were implemented more or less simultaneously; the so-called “kitchen sink” approach (Figure). A recent systematic review performed by ECDC identified this problem in virtually all studies evaluating control interventions for CRE.

Figure. Perceived relative importance of outbreak control interventions at NIH.

Figure. Perceived relative importance of outbreak control interventions at NIH.

There’s an interesting section on the ‘unintended consequences’ of publishing in report, including the inevitable scaremongering in some parts of the lay-press. It wasn’t all bad though; this is an unusually detailed article based on the original NIH outbreak report in the Washingtonian.

Some reflections from me:

- This all started with the transfer of a colonized patient from New York. Recognizing and containing colonized patients that are transferred from other hospitals is going one of the most important fronts in the battle against CRE. Worth noting that ECDC are recommending a rectal screen of all cross-border transfers of hospital patients in Europe.

- Mortality was especially high in the NIH outbreak (albeit in patients with serious underlying illness), illustrating the clinical ‘teeth’ that this issue bares.

- The outbreak reignited from an unidentified reservoir after apparently being brought under control; we have a limited understanding of the challenging epidemiology of these organisms.

- It’s sad, though not surprising, that the high hand hygiene compliance achieved during the outbreak could not be sustained following the outbreak.

- As you would expect, relying on clinical cultures only is looking at the tip of the iceberg. Active surveillance is a must.

- One unique aspect of their enhanced contact precautions was an instruction for staff to avoid touching personal electronic items. This makes a lot of sense, and should be considered for inclusion in regular contact precautions.

- There are some telling insights on the practical challenges of cohorting staff, not least the fact that there were not enough physicians to feasibly cohort!

- The initial isolation measures failed, and NIH (commendably) went to extraordinary lengths to bring the outbreak under control. ‘Aggressive’ is used to describe several aspect of their strategy, which seems apt. Israel is another success story of extraordinary CRE control measures. Greece and Italy are examples of where extraordinary measures have not been undertaken and CRE have quickly become endemic.

Article citation: Palmore TN, Henderson DK. Managing Transmission of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Healthcare Settings: A View From the Trenches. Clin Infect Dis 2013 in press.