I have a long flight to San Francisco to enjoy, which provides a perfect opportunity to relax and write my report from Infection Prevention 2013 Conference (Sept 30th – Oct 2nd 2013, London). The abstracts from the excellent submitted scientific material have been published as a free supplement in the Journal of Infection Prevention.

Opening lectures – Tricia Hart, Dale Fisher, Michael Gardam, Hugo Sax and Martin Kiernan

Following a short opening address from newly appointed IPS patron Prof Tricia Hart, exhorting us to put our patients before the numbers, Prof Dale Fisher from Singapore took the stage to talk about gaining organizational buy-in. With seamless reference to ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ throughout, most memorably “It’s not the problem that’s the problem; it’s your attitude to the problem that’s the problem” [Capt Jack Sparrow], Prof Fisher gave useful advice on gaining buy-in from all stakeholders, not just administrators. An interesting idea was to incentivize hand hygiene compliance by offering a substantial tax rebate. Another was to embrace the power of the media rather than running away scared. But, whatever you do, don’t be seen as a ‘rigid, dour zealot’.

Dr Michael Gardam from Canada was outstanding in his content (including perhaps the first ever hand gelogram) and delivery on using front line ownership to deliver patient safety. His resonating theme was ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’. Dr Gardam drew a thoughtful parallel between healthcare and raising children: challenging, private, rewarding, unpredictable, fun. This illustrated the ‘individuality’ of healthcare; each patient is different and should be treated individually. Equally, to achieve effective culture change, you need to empower the changee.

Prof Hugo Sax from Switzerland challenged the traditional approach of: perform hand hygiene ‘education’ then if that fails, educate some more and if that fails, make education mandatory! A consideration of fundamental human limitations was helpful: our finite capacity to process information per time unit; we are more likely to behave when being observed; and physiological responses affect our behavior (e.g. olfactory cues). These so-called ‘human factors’ must be embedded in our approaches to promote hand hygiene compliance.

To round off the morning’s lectures, Martin Kiernan delivered the EM Cotteral Lecture, revealing the life and times of the urinary catheter. Typically animated and innovative (including live tweeting as he was speaking), Martin outlined the challenges surrounding urinary catheters, including non-infectious risks. There is a remarkable lack of data and heterogeneity of practice for such a high-risk healthcare intervention. Although not quite finishing on a song, Martin did finish on a poem.

Submitted oral presentations: hand hygiene compliance and MRSA control

Paul Apler (Deb Ltd) presented an electronic system for monitoring hand hygiene compliance. The numerator is accurate, with each pump of hand gel logged electronically, but the denominator is derived from an algorithm for anticipated hand hygiene opportunities. The initial data look great, but the success or failure of the system depends on the accuracy of the denominator, which may need some tweaking for new settings. It does seem that the subjectivity and Hawthorne effect of hand hygiene monitoring would be reduced or perhaps even eliminated through automating the process.

Carolyn Dawson (University of Warwick) gave an overview of her research considering triggers for hand hygiene, with overtones of Prof Sax’s opening lecture. Inherent (“urgh”) triggers are more powerful than elective (“taught”) triggers hence inherent activities result in better compliance. We need to harness these fundamental human factors to achieve the highest possible rates of compliance. Carolyn has written an engaging blog-report of Infection Prevention 2013, which includes more details on her research.

Next up, I presented some work on MRSA admission screening at St. Thomas’ in London. An informal poll of the audience revealed that, surprisingly, the majority thought that targeted screening would detect less than 50% of carriers. Our study calculated that reverting from universal MRSA admission screening to a targeted approach would result in 75% (almost 22, 000) less screens but 45% (262) undetected MRSA carriers admitted. Is this enough to reconsider scrapping universal MRSA screening and returning to a targeted approach?

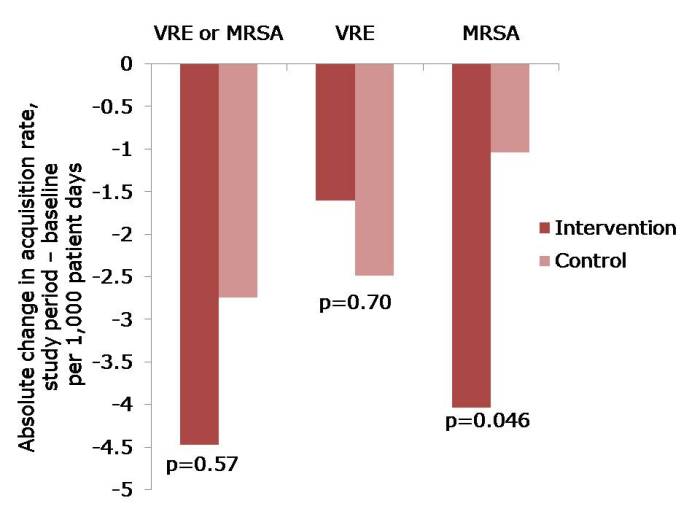

Debbie Weston (Kent) experienced a sizable outbreak of mupirocin-resistant MRSA, affecting 144 patients over 10 months. Amongst other interventions, the team made a sensible switch from mupirocin to fusidic acid and octinisan for MRSA decolonization and screened staff for MRSA carriage. Five staff carriers were detected, which could have been a factor in the continuation of the outbreak. This outbreak brings into sharp focus the risk of universal application of mupiriocin to ICU patients in a recent US study.

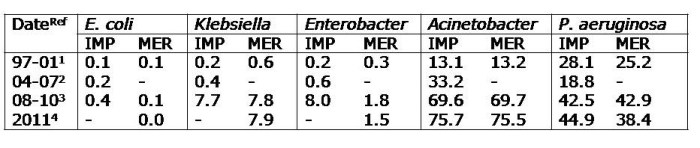

Multidrug resistant Gram-negatives

An important forum for discussing the challenges presented by multidrug-resistant Gram-negatives began with Prof Peter Wilson (UCLH) summarizing:

- Issues driving the “next MRSA”: antibiotic abuse in humans & animals; gastrointestinal carriage; complex, challenging sources; and rapid transmission.

- [Scant] evidence for effective interventions: screening; isolation; staffing; enhanced disinfection (consider hydrogen peroxide vapour); antibiotic stewardship; ward closure (perhaps).

- Research needs: gastrointestinal carriage rates; importance of imported cases; selective digestive decontamination (SDD); human vs. animal transmission; how best to improve cleaning.

Craig Bradley (Birmingham) then related his experience of controlling outbreaks of MDR A. baumannii highlighting the importance of environmental disinfection, and Alice Nutbourne (King’s, London) warned that empirical antibiotic therapy may be ineffective for an increasing proportion of Gram-negative sepsis cases.

Medical stats with Tim Boswell

Dr Tim Boswell (Nottingham) provided a useful, practical overview of how to tell whether an observed difference is due to chance. Covering theory, an overview and appraisal of available software and worked examples, this session provided a framework for understanding the difference between clinical and statistical significance.

Copper surfaces, “no-touch” automated room disinfection (NTD) and single rooms

Prof Tom Elliot (Birmingham) presented the impressive and ever-accumulating evidence for the introduction of copper surfaces in healthcare. Useful to note one cited paper from the 1980s showing that brass door handles were less likely to be contaminated than stainless steel ones, so the concept is hardly new. The data for copper surfaces are now impressive, with the Salgado study suggesting clinical impact. However, I still have questions over acceptability, durability and cost-effectiveness.

Gail Locock (Maidstone) then continued the estates theme with a view from her hospital, which is 100% single rooms. This iconic image perhaps best explains the reason why the switch to 100% single rooms was made, with the patients “so close tougher they could hold hands”. Whilst the infection prevention benefits of 100% single rooms are obvious, challenges include: patient visibility and associated safety, managing dementia, complacency, cleaning turnaround times, auditing compliance with hand hygiene and cohorting difficulties. Gail’s conclusion: pros and cons!

Prof Dale Fisher concluded the estates theme by addressing whether it is time to turn to “no-touch” automated room disinfection (NTD). Prof Fisher outlined the rationale for considering an NTD system; principally the ‘prior room occupancy’ data combined with the fact that conventional methods do not reliably eliminate pathogens. Several different NTD systems are available (mainly hydrogen peroxide vapour or aerosol, and ultraviolet C or pulsed-xenon), each with advantages and disadvantages. Technology can help, but you need to understand the limitations. In a way, NTD systems have redefined the standard for hospital hygiene, but workflows need to be adjusted if they are to be successfully implemented.

Submitted oral presentations: ‘Get Stoolsmart’ and hub contamination

The impressive and Twitter innovating Coventry IPS team gave an entertaining overview of their ‘Get Stoolsmart’ campaign, aiming to return clinical judgment to front line clinicians (with overtones of Dr Gardam’s opening lecture).

Dr Maryanne Mariyaselvam (Kings Lynne) found that 90% of needle-free IV connectors were contaminated with bacteria whereas only 33% of open hubs remained contaminated after flushing. What’s the answer? ”Scrub the hub” or new technology (including the connector impregnated with an antimicrobial under development by Dr Mariyaselvam and colleagues)?

Infection Prevention and Control in Japan – Prof Kobayashi

Prof Kobayashi (or ‘Kobayashi-sensei’!) provided a historical perspective on the development of an IPC programme in Japan. As a cardiac surgeon turned IPC champion, Prof Kobayashi has decades of experience to relate. Ultrasonic chlorhexidine baths for hand hygiene turned out to be a bad idea due to Gram-negative contamination, but the implementation of hand gels, link nurse programmes and temporary side rooms in Japan under the expert stewardship of Prof Kobayashi were years ahead of their time.

International Forum on Infection Prevention and Control

Internationally renowned speakers representing Asia (Prof Dale Fisher), the USA (Robert Garcia), Europe (Prof Hugo Sax) and England (Carole Fry) presented their biggest IPC successes and challenges:

It was encouraging to hear the experts celebrating their success, sharing ideas and embracing the challenges. From my viewpoint, the common challenge is the threat of CPE, which have the potential to spread globally like wildfire and make antibiotics virtually redundant.

Peter Hoffman on wipes

There’s been an explosion in the use of detergent and disinfectant impregnated wipes for hospital disinfection. Parents of young children in particular will understand the convenience of wipes over “wet bucket” approaches. But how do the data look in terms of efficacy? Peter Hoffman (PHE) outlined the challenges for wipes including: variations in microbial susceptibility, dealing with soiling, achieving adequate contact time with a small amount of wetting, large / intricate areas, choosing an appropriate active chemical and the dangers of sequential wiping transferring contamination. Importantly, Peter demonstrated that adding a sporicidal chemical to a wipe does not necessarily make a sporicidal wipe. Depressingly, it seems that choosing disinfectant wipes currently relies on manufacturers’ data using non-comparable testing. Conventional suspension tests and surface tests are meaningless for wipes so an accepted standard test for wipes (like this one from the Maillard Cardiff lab) is required urgently.

Keynote addresses – Jane Cummings, Aidan Halligan

The Chief Nursing Officer, Jane Cummings, spoke on unraveling and harnessing the potential of the complex ‘new’ NHS, aided by this useful infographic. The address included discussion on a new initiative: ‘6Cs Live’, which looks like an invaluable resource. The CNO concluded with a powerful patient-centred video entitled ‘Empathy’.

The video aptly introduced the theme of Prof Aidan Halligan’s address on rediscovering lost values in the NHS. Prof Halligan was disarmingly honest and forthright with the need to put patients first, poignantly citing Martin Luther King: “Our lives begin to end the moment we become silent about things that matter”. Focusing on empathy and compassion, and having the courage to challenge poor behaviour in a ward environment that can sometimes feel like a warzone is challenging and mistakes will be made. But try we must!

Submitted oral presentations – CPE at King’s and HPV at Tommies

Anita Verma (King’s, London) discussed the challenges of managing an outbreak of VIM-producing CPE on a paediatric unit affecting 11 patients in 2012. The outbreak response included the development of a detailed care plan, enhanced cleaning and transfer guidance for other hospitals. Despite several challenges (including poor adherence to IPC standards; suboptimal cleaning and disinfection; lack of awareness by caregivers, staff and visitors; and young patients in nappies), the outbreak was successfully controlled.

David Tucker (Guy’s and St. Thomas’, London) described a comparison between the length of time and cost of disinfecting rooms and bays using conventional methods of hydrogen peroxide vapour (HPV). Surprisingly, the HPV process time (including pre-cleaning) was only marginally longer for rooms and bays, and HPV was marginally more expensive for rooms and cheaper for bays. These findings are at odds with the general perception that HPV takes considerably longer and is much more expensive than conventional methods.

Clostridium difficile – search and destroy

Search – Dr Simon Goldenberg (Guy’s and St. Thomas’, London) addressed some problematic epidemiological definitions for C. difficile, which result in confusion and make true “CA-CDI” difficult to identify. Relatively recent data on C. difficile testing suggests that ‘you’d be better off flipping a coin than using some toxin EIA tests for CDI diagnosis’. Fortunately, DH diagnosis guidelines are now clear!

Destroy – Myth-busing Dr Jimmy Walker (PHE) provided some invaluable advice on choosing a sporicide active against C. difficile. Practically speaking, Dr Walker reminded us of the need for effective cleaning prior to disinfection for both disinfectant activity and aesthetics, and to look out for material compatibility problems when using sporicides. Specifying appropriate in vitro tests for sporcidies is challenging, but a 60 minute contact time is completely unrepresentative: you’d be lucky to achieve 6 minutes in the field; 6 second is probably more realistic. Dr Walker urged us not to be passive purchasers, but to check and challenge manufacturers’ (sometimes bogus) sporicidal claims.

Closing lectures – Barry Cookson, Phil Hammond, Didier Pittet and Julie Storr

Prof Barry Cookson delivered the Ayliffe Lecture on the past, present and future of MRSA. Prof Cookson described the 1970s as the decade of complacency, the 1980s of re-emergence, the 1990s of dawning realization, the 2000s of reactivity and the 2010s of uncertainty. My alternative view is: 1970s close shave; 1980s warning signs; 1990s unchecked; 2000s action, finally; 2010s ‘post’ MRSA era. The conclusion was to learn from the past to safeguard the future, with Prof Cookson remaining fearful of future failure if effective surveillance systems are not in place and maintained.

Dr Phil Hammond lit up the room with his insightful and, at times, downright hilarious commentary on speaking the truth to power (for example, his silencing of Andrew Landsley on Question Time), on not commoditizing healthcare; on restructuring the NHS; on dark stories about gagging whistleblowers; and on transparency. His summary: the ‘top-down’ restructuring of the NHS has failed; we need to develop care partnerships with our patients.

Newly appointed patron Prof Didier Pittet inspired us to begin with the end in mind, focusing on what we want to be and do, followed by final uplifting words from the Julie Storr, the IPS President.

Overriding themes

Infection Prevention 2013 provided some useful food for thought and discussion:

- Try new ways to achieve culture change (for example, empowering your culture changees [Gardam], embracing the media [Fischer], and ‘putting the love back into infection prevention and control’ [the irrepressible Coventry IPC team]).

- Where and when can automation help (monitoring hand hygiene compliance, terminal disinfection)?

- What on earth do we do about MDR Gram-negatives, specifically CPE?

- How to do more for less, maximize the opportunities of the ‘new’ NHS, whilst retaining compassion and empathy as core values?

Figure: Epidemiology relationships between 333 genetically related cases. ‘Ward contact’ = shared time on the same ward; ‘Hospital contact’ = shared time in the same hospital, without direct ward contact; ‘Ward contamination’ = admitted to the same ward within 28 days of the discharge of a symptomatic patient; ‘Same GP’ = no hospital contact, but shared the same GP; ‘Same postcode’ = no hospital contact, but shared the same postal code).

Figure: Epidemiology relationships between 333 genetically related cases. ‘Ward contact’ = shared time on the same ward; ‘Hospital contact’ = shared time in the same hospital, without direct ward contact; ‘Ward contamination’ = admitted to the same ward within 28 days of the discharge of a symptomatic patient; ‘Same GP’ = no hospital contact, but shared the same GP; ‘Same postcode’ = no hospital contact, but shared the same postal code).