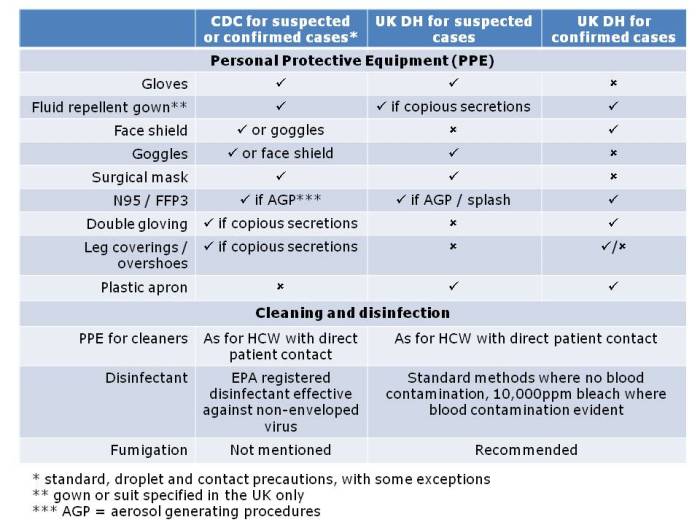

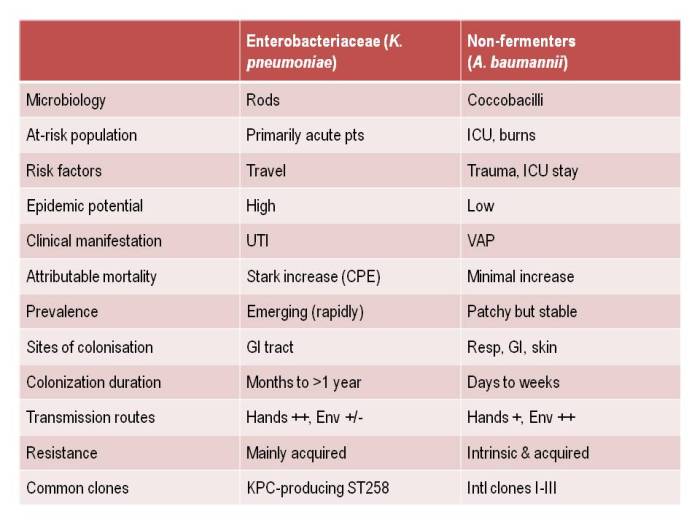

Apples and oranges. They’re both more or less spherical and classified as fruits, and that’s about whether the similarity ends. It’s the same for antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (e.g. Klebsiella pneumoniae) and non-fermenters (e.g. Acinetobacter baumannii): they both share the same basic shape (more or less) and classification (Gram-negative), and that’s about where the similarity ends (see the Table below):

Table: Comparing the epidemiology of resistant Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters.

I gave a webinar yesterday as part of a three part series on resistant Gram-negatives. You can download the slides here, and access the recording here (although you’ll have to register to do so). I am increasingly hearing people talking about ‘carbapenem-resistant organisms’ (CRO), used as a catch-all term to encompass both the Enterobacteriaceae and the non-fermenters. As you can see from the comparison table able, this doesn’t make a lot of sense given the key differences in their epidemiology. Indeed, MRSA is a CRO, so why don’t we lump that together with the Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters? Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and carbapenem-resistant non-fermenters are both emerging problems, but they are not the same problem.

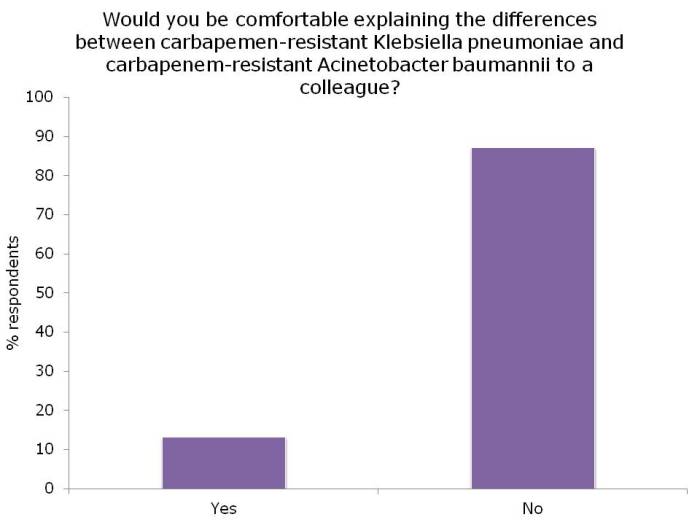

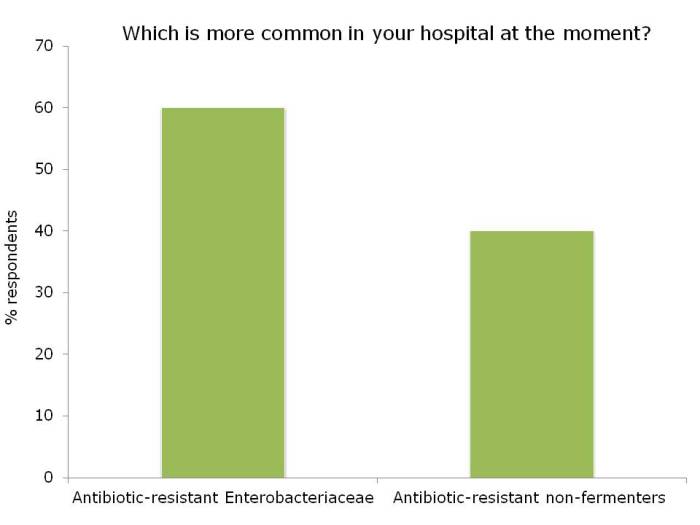

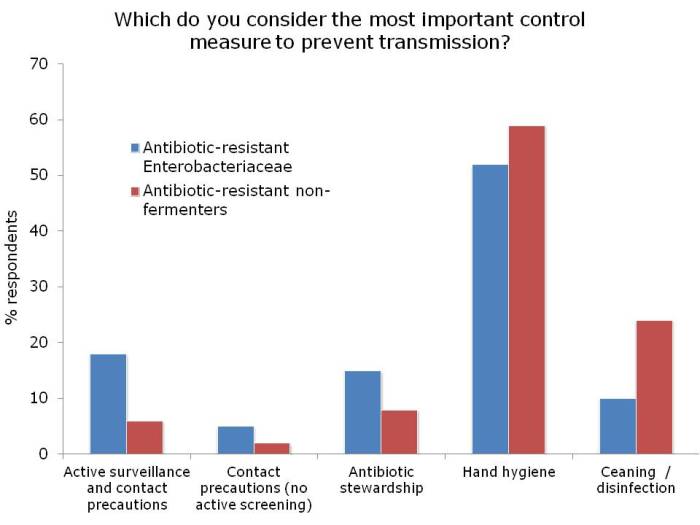

I asked a few questions of the audience, which I’ve summarised below:

Figures: Questions asked of around 150 webinar participants, mainly from the USA.

I was not surprised that so few people felt comfortable explaining the difference between the Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters – and this rather justified the whole thrust of the webinar! I was a little surprised that the ‘prevalence’ of the two groups of resistant bacteria were so similar; I was expecting the Enterobacteriaceae to be more common (although I admit this wasn’t a brilliantly worded question). In terms of control interventions, it’s true that we still don’t really know what works to control resistant Gram-negative bacteria. But it does seem likely that the control interventions will be different for Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenters, and this did come across in the responses. Hand hygiene was selected by most people (which makes sense), with screening & isolation, and stewardship more commonly selected for Enterobacteriaceae, and cleaning / disinfection for the non-fermenters.

Q&A

Following the webinar, the audience asked a few interesting questions:

- Can you get chlorhexidine resistant organisms? A number of studies have hinted that reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine may be an emerging problem, (for example Batra, Otter, Lee and Suwantarat). But increases in bacterial MICs (for Gram-positive bacteria at least) appear to be a long way below the applied concentration. However, it’s worth noting that the measured CHG skin concentration in one study (15-312 mg/L before the daily bath and 78-1250 mg/L after the daily bath) was much lower than the applied CHG concentration (10,000 mg/L). This is around the CHG MIC for some Gram-negatives and potentially brings the subtly reduced susceptibility to CHG reported in MRSA into play. On balance though, the rationale and data on reduced susceptibility are cautionary but not enough to recommend against universal use in the ICU given the clinical upside.

- Do you think we should be doing universal chlorhexidine bathing? On our ICU in London, we have been using universal chlorhexidine decolonization for a decade combined with targeted screening and isolation, and have seen a dramatic reduction in the spread of MRSA. So yes, I think we should be doing universal chlorhexidine bathing, but the need to monitor carefully for the emergence of clinically-relevant reduced susceptibility.

- Can we discontinue contact precautions for CRE? The short answer is no. Quite a few studies have found that gut colonization with CRE typically lasts for at least 6 months to >1 year. And those that become spontaneously ‘decolonised’ sometimes revert to colonized, suggesting that they weren’t really decolonized at all – it’s just that their load of CRE at the time of sampling had fallen below the limit of detection. So I favour a “once positive, always positive” approach to CRE colonization.

- Which disinfectant would you recommend for resistant Gram–negatives? It does seem that the non-fermenters (and in particular A. baumannii) are “more environmental” than the Enterobacteriaceae. However, the Enterobacteriaceae (including CRE – especially K. pneumoniae) can survive on dry surfaces for extended periods. Therefore, I think enhanced disinfection – especially at the time of patient discharge – is prudent for both groups. Consider using bleach or hydrogen peroxide-based liquid disinfectants, and terminal disinfection may be a job for automated room disinfection systems, such as hydrogen peroxide vapour.

- Should we use objective tools to monitor cleaning? Effective tools are available to objectively monitor cleaning (e.g. ATP and fluorescent dyes), and these have been shown to improve surface hygiene. Therefore, we should all now be using these tools to performance manage our cleaning processes.

Image credit: ‘Apples and oranges’.