For those of you who have had your head in a hole all week, you may not be aware that today is European Antibiotic Awareness Day, which coincides with Global Antibiotic Awareness Week. The antibiotic stewards amongst us (which should really be all of us!) have launched many and varied campaigns to highlight the need to handle antibiotics, our ‘miracle drugs’, with care (see Andreas’ 30-second-antibiotics-myth-buster-survey, for example).

Author: Jon Otter (@jonotter)

UK guidelines for the control of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria

The UK guidelines for the prevention and control of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (MDR-GNB) are published this week. It’s useful that the publication of these guidelines coincides with Antibiotic Awareness Week because MDR-GNB are brining us ever closer to the end of antibiotics. Although the guidelines don’t cover the treatment of MDR-GNB (this will be addressed in a forthcoming guideline), these highly resistant MDR-GNB leave few therapeutic options. Even when they remain susceptible to some antibiotics, these antibiotics are not front-line antibiotics for a reason (including poor tissue penetration and side effects). Furthermore, we are already seeing resistance to last-line (aka end of the golden-antibiotic-road) antibiotics e.g. colistin. Therefore, the old adage that ‘prevention is better than cure’ has never been so true!

Appraising the options for detecting carbapenemase-producing organisms

Carbapenemase-producing organisms (including CPE) present important clinical challenges: the “triple threat” of high levels of antibiotic resistance, virulence, and potential for rapid spread (locally, regionally, nationally, and globally)! However, these organisms somewhat ironically also present challenges to detection in the clinical laboratory. You’d expect that since these organisms are so important clinically they’d be dead easy to detect in the clinical lab – but this isn’t the case.

A comprehensive review published in Clinical Microbiology Reviews provides an overview of the diagnostic approaches to detect carbapenemase producers in the clinical lab. Figures 6 and 7 of the review provide a useful overview of the two broad approaches you could take: culturing organisms on agar plates, or using nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAAT – most commonly PCR) directly from a rectal swab.

The room lottery: why your hospital room can make you sick

In this era of increasing patient choice, let’s imagine you were offered the choice between two identical looking hospital rooms. Your chances of picking up a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) are approximately doubled if you choose the wrong room. But you have no way of knowing which room is safest.

So what explains this lottery? The key information you have not been told is the MDRO status of the previous room occupants. One of the rooms was previously occupied by a patient with C. difficile, and if you choose this room, your risk of developing C. difficile infection doubles. And it’s not just C. difficile – this same association has been demonstrated for MRSA, VRE, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Underpinning this association is the uncomfortable fact that cleaning and disinfection applied at the time of patient discharge is simply not good enough to protect the incoming patient.

Guidelines to control multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: an ‘evidence-free zone’

I recently had a review published in CMI comparing EU guidelines for controlling multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (MDR-GNB). I included the following guidelines in my review: ECCMID 2014, Irish MDRO, PHE CPE, HPS CPE, ECDC systematic review on CPE (not strictly a guideline, but did include some recommendations). A couple of important points arise:

Molecular diagnostics for C. difficile infection: too much of a good thing?

A study in JAMA Internal Medicine suggests that we may be ‘overdiagnosising’ C. difficile in this era of molecular diagnostics. The researchers from California grouped the 1416 patients tested for C. difficile into three groups: Tox+/PCR+ (9%), Tox-/PCR+ (11%), and Tox-/PCR+ (79%) (see Figure). Perhaps unsurprisingly, compared with Tox+/PCR+ cases, Tox-/PCR+ cases had lower bacterial load, less prior antibiotic exposure, less faecal inflammation, a shorter duration of diarrhoea, were less likely to suffer complications, and were less likely to die within 30 days. Perhaps even more importantly, patients with Tox-/PCR+ were pretty much identical to patients with Tox-/PCR- specimens in all of these metrics. In short: these patients had C. difficile in their gut, but they did not have C. difficile infection. The key message here is that we should not be treating patients who are C. difficile “positive” by molecular tests only.

Reflections from Infection Prevention 2015 Part III: Thinking outside the box

For the third and final installment of my blog-report from Infection Prevention 2015, I thought I’d cover some of the more innovative approaches in and around the IPC sphere:

Part II: Improving the systems

Part III: Thinking outside the box

New technology to improve hand and environmental hygiene

I for one am pretty sick of seeing unrealistically high levels of hand hygiene compliance being reported from peer-to-peer manual auditing approaches. One way to get more realistic compliance data is through automated approaches to hand hygiene compliance, reviewed here by Drs Dawson (Warwick) and Mackrill (Imperial College London), who also presented their findings at the conference, and by another group here. Drs Dawson and Mackrill considered issues around product usage, self-reporting, direct observation, perceptions of technology (often viewed, unhelpfully, as a ‘silver bullet’), and staff perceptions of need and benefit. They divided the technology into those that monitored product usage, surveillance systems that monitored individual performance, and systems that monitored both product usage and individual performance. Although automated surveillance systems will always be imperfect and involve a degree of inference, would you rather monitor the 5 moments sporadically / badly or have robust measurements of a smaller number of moments? Automated surveillance methods will not replace manual audits – at least for now – but it’s time to take a long hard look at what is available.

Reflections from Infection Prevention 2015 Part II: Improving the systems

Welcome to the second installment of my blog-report from Infection Prevention 2015, focused on improving the systems around the delivery of safe healthcare, and infection prevention and control:

Part II: Improving the systems

Part III: Thinking outside the box

The economics of HCAI is going to become increasingly important as the NHS – and healthcare systems worldwide – continue to “seek efficiency savings” (aka demand more for less). So the overview of HCAI economics from Dr Nick Graves (QUT, Australia) was timely. I find it remarkable that we are still so reliant on the 2000 Plowman report to gauge the cost of HCAI – surely there must be a more sophisticated approach? There is something rather uncomfortable about setting an ‘acceptable’ level of HCAI, or putting a £ value that we would be prepared pay to save a life, but this is exactly what we have to do to manage the demands of scarcity. Dr Graves presented some useful worked examples to illustrate his point, around coated catheters, hip replacements, hand hygiene improvement, and MRSA screening. In most cases, there comes a point where a health benefit is too expensive to ‘purchase’, which is an uncomfortable but very real choice across all areas of healthcare (e.g. cancer drugs).

Reflections from Infection Prevention 2015 Part I: Beating the bugs

Infection Prevention 2015, the annual conference of IPS, was held in Liverpool this year. I’m delighted to say that the abstracts from the submitted science are published Open Access in the Journal of Infection Prevention. This first instalment of my report will be “bug-focussed”, followed by another two on different themes:

Part I: Beating the bugs

Part II: Improving the systems

Part III: Thinking outside the box

Opening lectures

The conference kicked off with fellow ‘Reflections’ blogger Prof Andreas Voss. By Andreas’ own admission, he was given a curve-ball of a title: ‘CRE, VRE, C. difficle or MRSA: what should be the priority of infection prevention?’ [No idea where that could have come from…] Andreas developed a framework for grading the priority of our microbial threats, accounting for transmissibility, virulence, antibiotic resistance, at-risk patients, feasibility of decolonisation, cost, and impact of uncontrolled spread. And the result? Any and all microbes that cause HCAI should be a priority of infection prevention. Even those that seem to have less clinical impact (such as VRE) are good indicators of system failure. If we focus too much on one threat, we risk losing sight of the bigger picture.

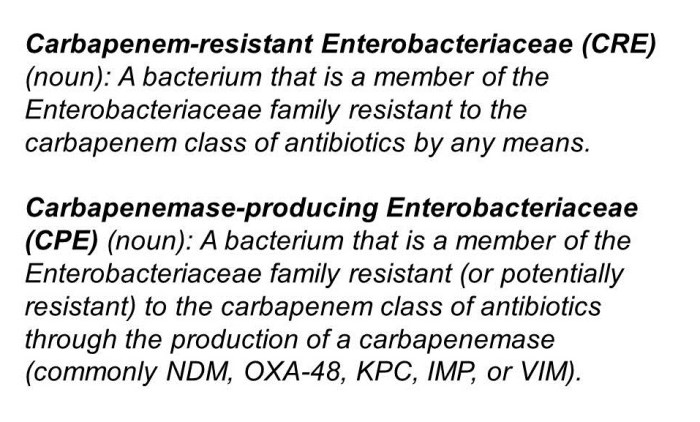

CRE -> CPE

I have thought a lot (probably too much) about the best way to describe the issue of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. I decided ages ago that CRE (a la the CDC) is the way to go as a generic term to describe the problem. But the more I think about it, the more I am coming around to the idea that CPE (a la PHE) is better. And here’s why:

- The real issue from a clinical and infection control viewpoint is CPE. Enterobacteriaceae that are resistant to carbapenems by means other than an acquired carbapenemase (i.e. CRE that are not carbapenemase producers) are important, but they don’t seem to have the same capacity to spread as carbapenemase producers.

- It’s a really confusing situation in terms of terminology. From the “end user” staff member on the front line and patient, all that really counts is whether it is a CPE or not. It’s really rather confusing to tell a patient that the have a “CRE that is also a carbapenemase producer” – easier just to say “you have a CPE”. (I accept that you will also need to tell a patient if they have a CRE that is not a carbapenemase producer – but I think this way around is easier.)

- CPE is already en vogue in the UK (mainly due to the PHE Toolkit) so using any other term risks confusion at the time of patient transfer. (Clearly, this point is reversed if you are working in the US!)

I still think that “CRO/CPO” is not the way to go, given the gulf in epidemiology between the Enterobacteriaceae and the non-fermenters (although, sometimes, begrudgingly, you have to go there). What I mean by this is that you will sometimes detect a carbapenemase gene from a PCR but don’t yet know whether it is from a non-fermenter or Enterobacteriaceae species. In this circumstance, this has to go down as a ‘CPO’.

So, there you have it, a personal U-turn. CRE -> CPE. But I wonder whether CDC and PHE and the international community will ever agree a common term…