The organizing committee of SHEA should be congratulated for putting together an interesting and engaging agenda for their Spring Meeting, based around the recent ICHE special edition. Sadly, I was only able to make it for ‘From MRSA to CRE: Controversies in MDROs’ at the tail end of the meeting.

Global perspective on CRE evolution – Dr Arjun Srinivasan

Dr Srinivasan kicked off with a frankly frightening status update on the ‘nightmare bacteria’. KPC and NDM-producing Enterobacteriaceae have spread globally and rapidly since 2006.1 The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae in the US has risen from 1% in 2001 to a whopping 10% in 2011.2 More worryingly, the prevalence of CRE colonization in long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs) in Illinois was 30% in a recent point prevalence survey.3 Arjun gave some useful perspectives on the mortality associated with CRE. The odds ratio for mortality attributable to CRE was remarkably similar in studies from Israel and the US at around 4 (which is approximately twice that of MRSA).4-6

Arjun made the point that 10% of CRE reported to the CDC are “community-acquired”. I find this hard to believe and I suspect they’d be healthcare-associated if you searched hard enough for risk factors. The picture would be different in areas of really high prevalence like New Delhi or Greece, but I don’t think the US is quite there yet.

Arjun highlighted some practical limitations of implementing strategies to control CRE, in particular around staff cohorting. “Today you’re assigned to work on the unit dedicated to patients with the nightmare bacteria”; not a popular message to our staff.

The key questions from Arjun’s viewpoint are: the focus has been on K. pneumoniae and E. coli, but should Enterobacter be in the mix? Are we doing enough to control CRE (or possibly, too much)? What are the right policy solutions in terms of reporting and guidelines? And finally, can we control CRE? An updated national report from Israel suggests yes.7 But uncontrolled spread elsewhere (e.g. Greece and increasingly Italy) suggest no.

Lab Identification & Surveillance for MDROs – Dr Daniel Diekema

Dr Diekema gave a timely and thoughtful overview of lab diagnostics for MDROs. One problem hampering clear lab diagnosis and surveillance is how to define an MDRO, and MDR-GNR in particular. Do we go by phenotype or by genotype? Clearly, there are arguments either way; there’s a tendency for clinicians to gravitate towards phenotype and scientists towards genotype I think, so we need to look out for our own biases.

The keynote was “don’t throw away the agar plates just yet”. Molecular diagnostics has a role, but it does not replace agar plates. Molecular diagnostics are great, but do not deal with changing epidemiology; struggle with target variability; are expensive; rely on validation of carriage sites; do not tell you about phenotypic susceptibility; have a limit of detection often around a couple of logs; and need to manage shared resistance genes between species, especially for MDR-GNR. Dan concluded by questioning whether molecular diagnostics remain the realm of reference, referral and research labs!

CRE in LTCF, LTACH, Regional Control – Drs Kerri Thom & Michael Lin

Dr Thom gave a rather disturbing overview of the involvement of long-term care facilities (LTCFs) and LTACHs as reservoirs for the spread of CRE. She began by providing evidence, albeit from outbreaks, that standard hand hygiene focus and contact precautions do not control CRE spread.8,9 You need to do more: active surveillance cultures plus cohorting has worked in a number of studies.8,10,11 Several studies suggest a significant LTCF / LTACH reservoir.3,12-14 A study from 2011 carefully studying regional spread of CRE through analysis of inter-facility “social networks” suggests that a connected regional approach to control is required.12

Dr Lin, working in the “CRE battleground of Illinois”3 continued the theme for a regional approach by presenting a regional collaborative to register CRE carriers: the XDRO registry. Dr Lin referred to a successful CRE LTACH bundle, which was presented at ID Week 2013, and provides some hope that CRE can be controlled in LTACHs.

Posters and oral presentations

The SHEA Spring Meeting had some posters for the first time, which was a welcome addition. The highlights from the posters were:

- Dr Lesho: 75 million person years of surveillance in US military yields 300 CRE cases; 1 per 100,000 person years.

- Dr Mann: Sharklett pattern surfaces performed better than copper for reducing bacterial persistence and transfer.

- Southard: Pulsed-xenon UV disinfection of ICU rooms following ALL discharges associated with 20 v 6 cases of unit-attributable CDI.

- Nicole Kenny: If your microfiber is too absorbent, you can forget about a 10 minute contact time.

Four impressive submitted abstracts were presented:

- Dr Assadian performed an RCT of antimicrobial surgical gloves, demonstrating an impressive microbiological reduction – but will this translate to clinical benefit?

- Dr Cluzet found that recurrent MRSA colonization occurred in 40% of 200 patients with uncomplicated MRSA skin and soft tissue infection in the community, and was associated with colonized household contacts and some antibiotics.

- Dr Decker found that CRE colonization duration was a mean 241 days (range 38-649). Worrying, a few patients followed a ‘pos-neg-pos’ colonization pattern, which supports a “once colonized, always colonized” approach.

- Dr Kwon performed a beautiful RCT of Lactobacillus probiotics, but sadly found that it did not reduce GI MDRO colonization or acquisition.

Contact Isolation Precautions: Unanswered Questions – Dr Daniel Morgan

Dr Morgan gave a very balanced and data-led overview of the pros and cons of contact isolation precautions. On the one hand, gloves and gowns are frequently contaminated with MDROs (which would be hands and clothes if no gloves and gowns).15 On the other hand, the somewhat equivocal findings of the BUGG study do not exactly provide resounding support for contact isolation precautions.16 Also, patients under contact precautions have less contact with healthcare personnel, delayed discharge, an increased risk of adverse events, potential for psychological problems, and reduced patient satisfaction. Dr Morgan’s conclusion was complex (matching the data), with a graded approach to contact isolation precautions advocated: CRE > C. difficile > MRSA > VRE.

Success Stories in MRSA Control – Drs Sarah Haessler, Michael Edmond, Steven Gordon and Jeffrey Stark.

This session was not quite what I was expecting. It turns out that all four speakers have stopped using contact precautions for MRSA colonized patients, so this became a collective justification for this practice. The arguments are compelling: none of the speakers’ MRSA rates skyrocketed when they stopped isolating MRSA patients. The alternative approach to traditional contact precautions seems to be a ‘syndromic approach’: basically, only isolate them if they’re oozing. I can see the logic here, but there may be exceptions. For example, MRSA colonized patients with respiratory viruses can enter a “super-spreader” state and would most certainly not be obviously oozing.17 Also, I wonder whether the faculty would feel differently about contact precautions if they were working outside the US in a healthcare system that is mainly composed of 4 and 6 bed bays (like most NHS hospitals)?

Top 10 MDRO Papers – Drs Susan Huang & Ebbing Lautenbach

Dr Huang selected:

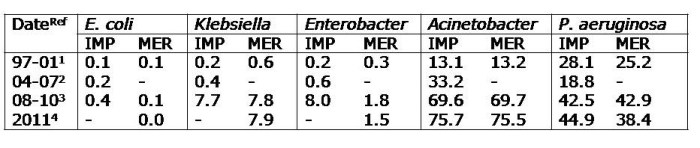

- Sivert NHSN data, demonstrating high rates of carbapenem resistance in CLABSI: 23% of Klebsiella, 26% of Pseudomonas and 65% of Acinetobacter.18

- Rutala study showing that reflective paint results in rapidly reduced UVC cycle times and thus improves feasibility.19 (I think there’s probably two views on this study. Either the reflective paint resulted in more reflective bouncing of the UVC around the room and genuinely improved things. Alternatively, the reflective paint could have reflected the UVC directly back to the sensor more rapidly and actually reduced the dose delivered to the microbes on the surfaces.)

- Harris BUGG study, which is testament to securing big funding for definitive studies (though with frustratingly equivocal results).16

- Huang etc universal intervention studies.20-22 Universal chlorhexidine bathing: YES (provided resistance is monitored). Universal mupirocin decolonization: NO!

Dr Lautenbach chose:

- van Nood faecal transplant for preventing C. difficile recurrence.23 ‘Transpoosions’ work, but we need to work on finding the right synthetic bug mix. Dr Lautenbach described the findings of the faecal transplant study as a “penicillin moment”; it’s a concept that could transform medicine.

- Eye Oxfordshire C. difficile whole genome sequencing study: how much CDI is hospital-acquired?24 The study did not consider asymptomatic carriers or environmental contamination and 25% of patient isolates were not available for analysis. So, there was a pretty large potential burden from which hospital-acquisition could have occurred.

- Lin LTACH CRE colonization study.3 30% of patients carried CRE; this figure was 55% in one of the facilities included in the survey.

- Daneman selective decontamination study.25 I can’t help thinking that ‘selective decontamination’ is misnamed: it’s not very selective at all. Perhaps ‘scorched earth decontamination’ would be more accurate. My view is that, regardless of efficacy, we should be giving faecal transplantation before a cocktail of antibiotics. Let’s save the antibiotics for treating infections.

- Gerber community-based antibiotic stewardship cluster RCT, which showed an impressive reduction in broad spectrum antibiotic prescribing.26

Fecal Transplant for C. difficile Infection – Dr Michael Edmond

Dr Edmond gave a passionate and first-hand case for the effectiveness and value of faecal transplantation for recurrent CDI. It’s not a new concept: ‘faecal therapy’ was documented in Chinese medicine in 300AD; the first modern use was in 1957, with impressive results.27 Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) cures recurrent CDI by complementing reduced microbiota diversity.28 Indeed, a recent systematic review of FMT reported an overall cure rate of 91% for recurrent CDI.29 The regulatory position is in flux currently, meaning that purchasing carefully tested stool from the ‘brown cross’ (www.openbiome.org) may be more challenging in future. (Indeed, it may even come to DIY FMT, which is possible: first you collect it, then you blend it and then you stick it…) The bottom line is that fresh or frozen, yours or somebody else’s, stool bank or lab donor, NG tube or enema: FMT works for recurrent CDI. The only question is whether it could be a front-line treatment for CDI.

The Microbiome and Its Role in Infection Prevention – Dr Clifford McDonald

Dr McDonald gave a mind-bending talk on the hugely underestimated role of the microbiome in human disease. The gut microbiome is dominated by the Bacteroidetes or Firmicutes, depending on diet; coliforms are surprisingly minor players.30 Antibiotic therapy results in profound disruption of the gut microbiome;31 thus we need to carefully tend the microbiome.32 We need to consider ways to manipulate the gut microbiome for good, using perhaps ‘advanced’ probiotics or modulating bacterial inter-cell communication. Cliff finished with a thought-proving vision of the future involving extensive testing of the patient’s microbiome, a “tending” consultation and treatment with a course of the appropriate advanced probiotic therapy.

Pro-Con: Should We Be Bare Below the Elbows? Drs Michael Edmond & Neil Fishman

The recently published SHEA guidelines on attire provide some useful background.33 Dr Edmond began with the pro position: clothing becomes contaminated with MDROs, which can be transmitted from clothing in laboratory studies; white coats are rarely washed; there is limited evidence but potential benefit. When evidence is limited, we need to avoid ‘methodolatry’, the worship of the hallowed RCT. It seems that a doctor’s appearance is the least important performance measure from a patient’s viewpoint.34 They are much more concerned with whether their doctor knows their stuff. Perhaps the most powerful argument of all for the pro is that Dr Edmond recently won an award for the best beside manner whilst dressing down.

Dr Fishman began his con in entertaining fashion: by undressing to bare below the elbow and replacing his neck tie for a fetching bow-tie. His argument was: unattractive bingo wings; bug-trapping hairy arms; may be some unintended harm; reduced patient experience; is it consistent when you consider policies for hand-held electronics; and, of course, no evidence.

The UK has been bare below the elbow for several years now. There has been some resistance: in fact, the debate reminded me of a London surgeon going apoplectic when the Prime Minister’s camera crew were not bare below the elbow during a hospital visit. So, should we be bare below the elbow? In my view, yes; it makes it easier to wash your hands. However, the manner in which you interact with you patient is far more important than what you wear.

Key issues

- Can we control CRE and, if so, how?

- Related to this, how to deal with the (apparently sizable) CRE reservoir in LTACHs?

- Do molecular diagnostics remain the realm of reference, referral and research labs?

- Has our focus on CRE taken our eye off multidrug-resistant non-fermenters (particularly A. baumannii), which are a greater ‘clear and present danger’ for many facilities?

- Can we risk abandoning contact precautions for MRSA patients? In a US hospital with 100% single rooms, perhaps. In the NHS composed of 4 and 6 bed bays, no.

- FMT works for recurrent CDI and regulators should not block access to it.

- Could FMT work as a front-line treatment for CDI?

- How can we modify the gut microbiome most effectively to confer infection prevention and control benefits?

- Is microbiome modulation more effective than antibiotic ‘selective decontamination?

References

1. Molton JS, Tambyah PA, Ang BS, Ling ML, Fisher DA. The global spread of healthcare-associated multidrug-resistant bacteria: a perspective from Asia. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1310-1318.

2. Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013; 62: 165-170.

3. Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K et al. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 1246-1252.

4. Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 53-59.

5. Patel G, Huprikar S, Factor SH, Jenkins SG, Calfee DP. Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29: 1099-1106.

6. Borer A, Saidel-Odes L, Riesenberg K et al. Attributable mortality rate for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30: 972-976.

7. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. An ongoing national intervention to contain the spread of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: 697-703.

8. Palmore TN, Henderson DK. Managing Transmission of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Healthcare Settings: A View From the Trenches. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 1593-1599.

9. Kochar S, Sheard T, Sharma R et al. Success of an infection control program to reduce the spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30: 447-452.

10. Agodi A, Voulgari E, Barchitta M et al. Containment of an outbreak of KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Italy. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49: 3986-3989.

11. Ben-David D, Maor Y, Keller N et al. Potential role of active surveillance in the control of a hospital-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31: 620-626.

12. Won SY, Munoz-Price LS, Lolans K et al. Emergence and rapid regional spread of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 532-540.

13. Marquez P, Terashita D. Editorial commentary: long-term acute care hospitals and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a reservoir for transmission. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57: 1253-1255.

14. Marchaim D, Perez F, Lee J et al. “Swimming in resistance”: Co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Infect Control 2012; 40: 830-835.

15. Morgan DJ, Liang SY, Smith CL et al. Frequent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii contamination of gloves, gowns, and hands of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31: 716-721.

16. Harris AD, Pineles L, Belton B et al. Universal glove and gown use and acquisition of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the ICU: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310: 1571-1580.

17. Sheretz RJ, Reagan DR, Hampton KD et al. A cloud adult: the Staphylococcus aureus-virus interaction revisited. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124: 539-547.

18. Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34: 1-14.

19. Rutala WA, Gergen MF, Tande BM, Weber DJ. Rapid hospital room decontamination using ultraviolet (UV) light with a nanostructured UV-reflective wall coating. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34: 527-529.

20. Climo MW, Yokoe DS, Warren DK et al. Effect of daily chlorhexidine bathing on hospital-acquired infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 533-542.

21. Milstone AM, Elward A, Song X et al. Daily chlorhexidine bathing to reduce bacteraemia in critically ill children: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, crossover trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 1099-1106.

22. Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K et al. Targeted versus Universal Decolonization to Prevent ICU Infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2255-2265.

23. van Nood E, Dijkgraaf MG, Keller JJ. Duodenal infusion of feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2145.

24. Eyre DW, Cule ML, Wilson DJ et al. Diverse sources of C. difficile infection identified on whole-genome sequencing. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1195-1205.

25. Daneman N, Sarwar S, Fowler RA, Cuthbertson BH, Su DCSG. Effect of selective decontamination on antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 328-341.

26. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 2345-2352.

27. Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery 1958; 44: 854-859.

28. Chang JY, Antonopoulos DA, Kalra A et al. Decreased diversity of the fecal Microbiome in recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Infect Dis 2008; 197: 435-438.

29. Sha S, Liang J, Chen M et al. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation therapy for digestive and nondigestive disorders in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; in press.

30. De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 14691-14696.

31. Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108 Suppl 1: 4554-4561.

32. Tosh PK, McDonald LC. Infection control in the multidrug-resistant era: tending the human microbiome. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: 707-713.

33. Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S et al. Healthcare personnel attire in non-operating-room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35: 107-121.

34. Aitken SA, Tinning CG, Gupta S, Medlock G, Wood AM, Aitken MA. The importance of the orthopaedic doctors’ appearance: a cross-regional questionnaire based study. Surgeon 2014; 12: 40-46.