Now that you have digested your Christmas turkey, I thought that it would be a good time to send out an update. These articles have been posted since the last update:

- Who’s harbouring CRE? (Published 22nd December 2014)

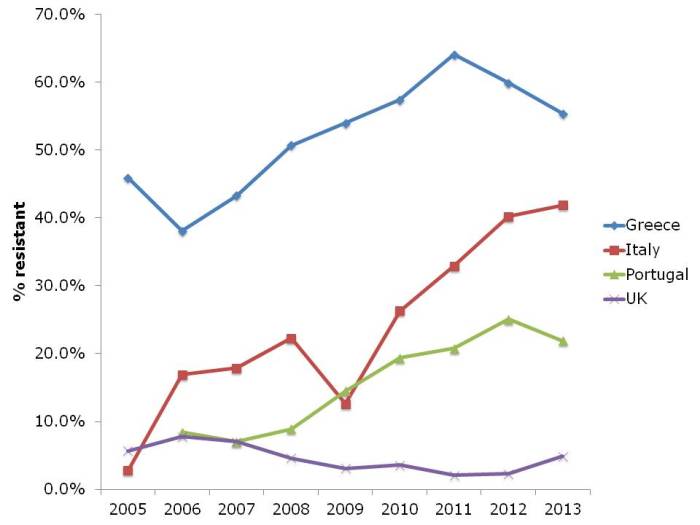

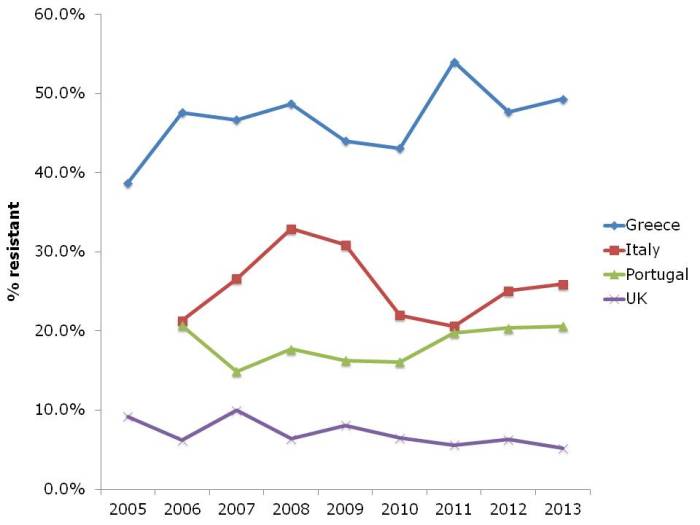

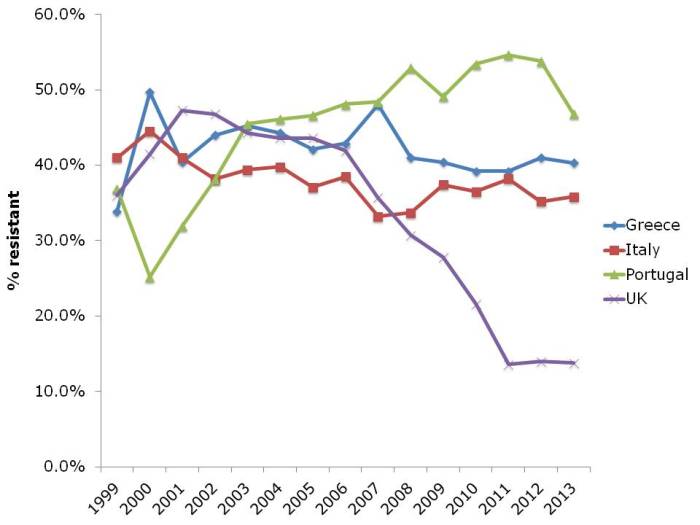

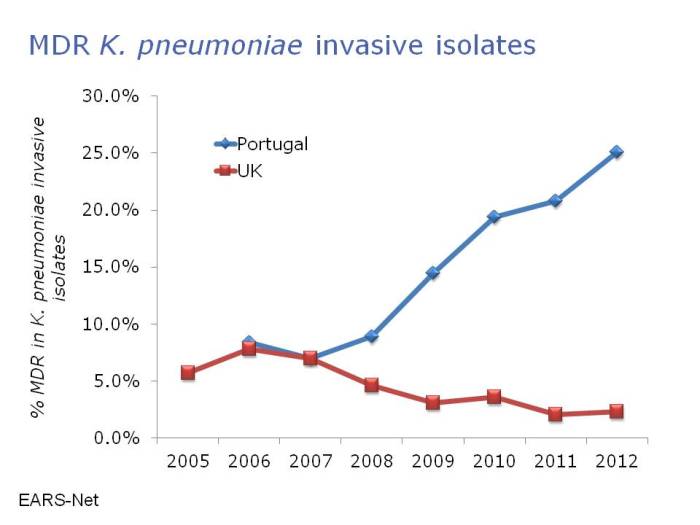

- ECDC data shows progressive, depressing increase in antibiotic resistance in Europe (Published 16th December 2014)

- Is deliberately seeding hospital rooms with Bacillus spores a good idea? No, I don’t think so either! (Published 8th December 2014)

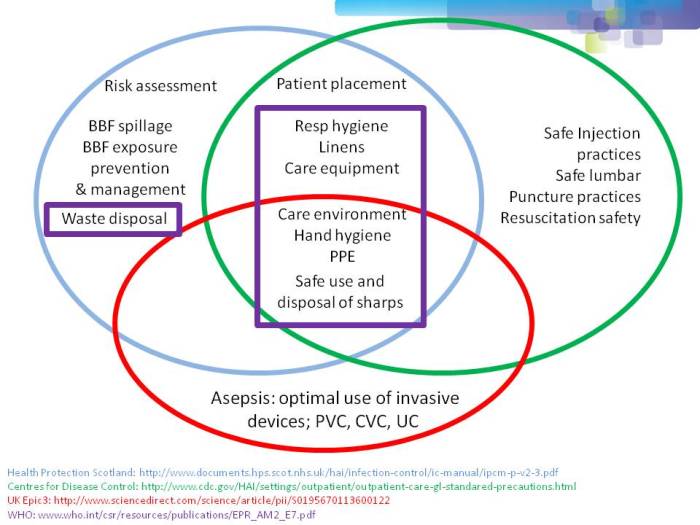

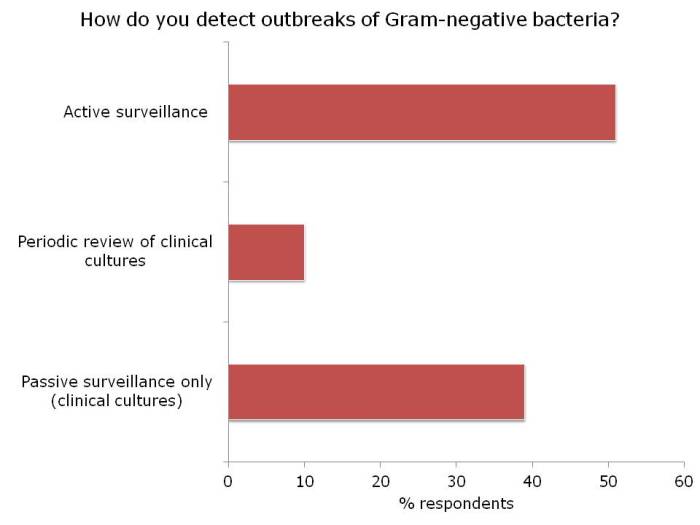

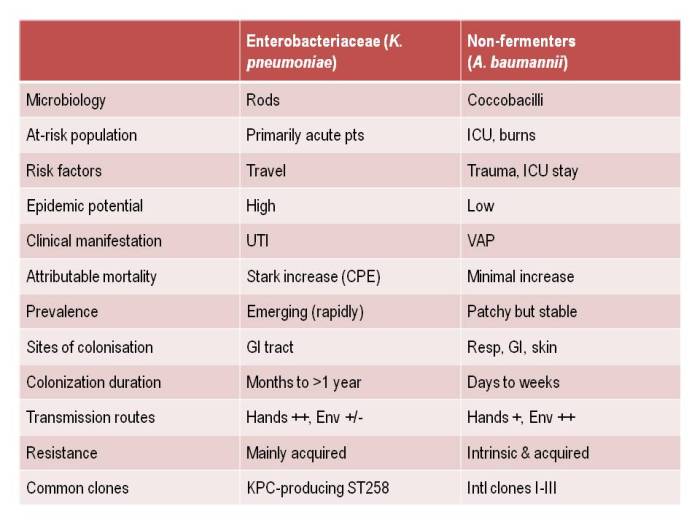

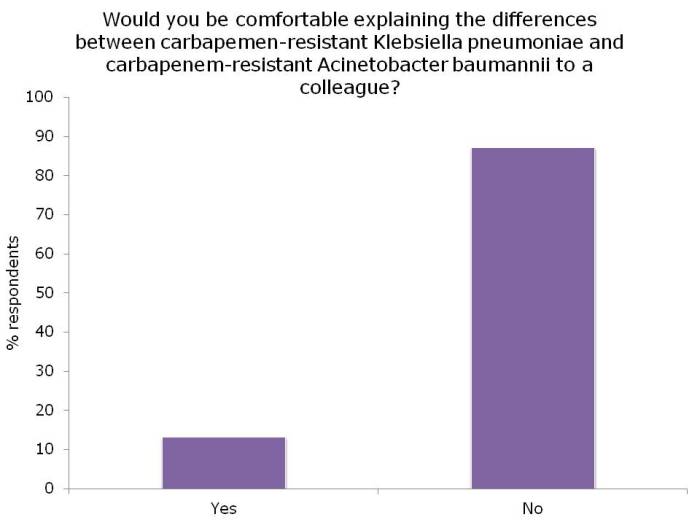

- Filling the gaps in the guidelines to control resistant Gram-negative bacteria (Published 2nd December 2014)

- Journal Roundup November 2014: Journal Roundup: Ebola (again), The rise (and rise) and fall of MRDOs & Infection Prevention 2014 (Published 28th November 2014)

- The inanimate environment doesn’t contribute to pathogen transmission in the operating room…OR does it? (Published 27th November 2014)

- Being bitten by antibiotic resistant CRAB hurts! (Acinetobacter that is.) (Published 25th November 2014)

- Reflections from HIS 2014, Part III: Education, communication, and antibiotic resistance (Published 21st November 2014)

- Reflections from HIS 2014, Part II: Dealing with the contaminated environment (Published 20th November 2014)

- Reflections from HIS 2014, Part I: Updates on C. difficile, norovirus and other HCAI pathogens (Published 19th November 2014)

- What’s trending in the infection prevention and control literature? (Published 16th November 2014)

- HIS Poster Round: Dealing with contaminated hands, surfaces, water and medical devices (Published 15th November 2014)

- Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): so what should an infection prevention and control team do now? (Published 11th November 2014)

- A postcard from Portugal: “Some days we don’t have any needles on the ICU” (Published 5th November 2014)

- Ebola: infection prevention and control considerations (Published 30th October 2014)

- ID Week 2014 as seen by an Infection Preventionist (Published 28th October 2014)

- Selective Digestive Decontamination (SDD) is dead; long live faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) (Published 27th October 2014)

I’m in a rather reflective mood, so time to remind you of some of the key themes from 2014: Ebola, MERS-CoV, universal vs. targeted interventions, faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), whole genome sequencing (WGS), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), and some interesting developments in environmental science. And what will we be still talking about come Christmas 2015? Let’s hope it won’t be Ebola, and I think that WGS will be a lab technique akin to a Vitek machine rather than subject matter for NEJM. But I think we still have ground to cover on whether to go for universal or targeted interventions, FMT, and improving our study designs in infection prevention and control. I can also foresee important studies on the comparative and cost-effectiveness of the various tools at our disposal.

And finally, before I sign off for 2014, a classic BMJ study on why Rudolf’s nose is red (it’s to do with the richly vascularised nasal microcirculation of the reindeer nose, apparently).

Image: Christmas #27.