Guest blogger and Acute Medicine trainee Dr Nicola Fawcett (bio below) writes…As the local Prophet of Antibiotic Resistance Doomsday to our population of hospital physicians, I’m always interested in finding out if the pan-drug-resistant superbug has emerged that is going to wipe us all out, for credibility purposes if nothing else. (Resistance Is Coming! Prepare thyself! Wash thy hands and document thy indication and duration or face Everlasting audits and perpetual personal protective equipment!). For the record – I’m actually a Registrar in Acute and General (Internal) Medicine. I’m doing some time in the world of ID/Micro/Genomics in the hope that it will help me work out whether it’s ok to just hand out co-amoxifrusiclavamide + nebs to everyone if not sure what’s going on. However this question seems rather inextricably linked to antibiotic resistance, and having spent some time now with people who seem to know what they’re doing, I’m increasingly flabbergasted at the massive divide between the views of microbiologists who see the latest data, and the views of the common garden hospital physician. Therefore my side-mission, if you like, has become to spread the good, or rather, spectacularly bad news that antimicrobial resistance is currently spreading around our biosphere at a scale and speed at which we simply cannot react fast enough.

antibiotic resistance

More of a bad thing: ESBL-E

In a short, but important Dutch study, the added value of selective pre-enrichment for the detection of ESBL-producing enterobacteriacea (ESBL-E) was evaluated. The authors used their yearly prevalence study to shed more light onto the question if pre-enrichment (using a broth) might be equally improving the performance of ESBL-E detection, as it does with MRSA. While the literature on the topic might be controversial, this straightforward, well-performed study showed that direct culture failed to identify 25.9% (7/27) ESBL-E rectal carriers, which corresponds to 1.2% (7/562) of the screened population. While the overall rate of ESBL-E rectal carriage is not very high (4.8%) this study still demonstrates the importance of improving our methods to detect multi-drug resistant pathogens.

The cat and mouse of antibiotic resistance (Tom never does catch Jerry…)

Prof Laura Piddock’s team from Birmingham recently published a Nature review on molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. If you’re struggling to tell your KPC from your NDM, this review is for you. Continue reading

Prof Laura Piddock’s team from Birmingham recently published a Nature review on molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. If you’re struggling to tell your KPC from your NDM, this review is for you. Continue reading

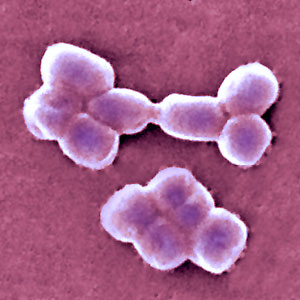

We need new antibiotics for Gram-negative, not Gram-positive bacteria

The threat from antibiotic resistance is more pink than purple. You probably need to be a microbiologist to get this: Gram-positive bacteria (such as MRSA and C. difficile) stain purple in the Gram stain, whereas Gram-negative bacteria (such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii*) stain pink. All of the international concern surrounding antibiotic resistance from the WHO, CDC, PHE and others have focused our mind on one threat in particular: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). The Enterobacteriaceae family of bacteria are all Gram-negative, so we need to focus our drug discovery towards the Gram-negatives rather than the Gram-positives.

I blogged last week on the fanfare surrounding the discovery of Teixobactin. Whilst it looks promising, it’s still a long way from the pharmacy shelves, is most certainly not “resistance-proof” and, most importantly, only active against Gram-positive bacteria. I’ve received some useful comments in response to the blog pointing me in the direction of another novel antibiotic, Brilacidin.

Brilacidin is a novel antibiotic class that is in many ways more promising than Teixobactin, not least due to its activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Furthermore, it’s much closer to the pharmacy shelves, having undergone promising Phase 2b clinical trials (showing broadly comparable efficacy to daptomycin for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections).

Brilacidin is not without its problems though. Firstly, it is not active against A. baumannii. This is important, since multidrug-resistant – especially carbapenem-resistant – A. baumannii is a serious problem in ICUs around the world. Secondly, although the antibiotic is truly novel (working on the principle of ‘defensin-mimetics’), manufacturer claims that resistance is ‘unlikely’ are as fanciful as the “resistance-proof” claims associated with Teixobactin. Every class of antibiotics was novel once. And resistance has developed to them all!

There are some other emerging options for the antimicrobial therapy of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. A number of beta-lactamase inhibitors combined with existing antibiotics are currently at various phases of the clinical trials process (for example, avibactam and MK-7655). Again though, although promising, beta-lactamase inhibitors have limitations, the most important being their specificity. For example, these inhibitors are effective against only some beta-lactamases (and have a blind spot for the metallo beta-lactamases such as NDM-1).

So, there is no silver bullet coming through the pipeline. And there will be no silver bullet. However clever we are in discovering or designing new antibiotics, some bacteria will always find a way to become resistant. It would be naive to think otherwise. Drug discovery is one part of our response to the rising threat of antibiotic resistance, but we ultimately need to focus on prevention over cure.

* Actually, A. baumannii is a bit “Gram-variable” so is somewhat pinky-purpley – but let’s not get too hung up on that.

Image credit and caption: Marc Perkins. ‘Gram stain demonstration slide. A slide demonstrating the gram stain. On the slide are two species of bacteria, one of which is a gram positive coccus (Staphylococcus aureus, stained dark purple) and the other a gram-negative bacillus (Escherichia coli, stained pink). Seen at approximately 1,000x magnification.’

ECDC data shows progressive, depressing increase in antibiotic resistance in Europe

The ECDC recently released their 2013 report, which includes 2013 data. The data are on the whole fairly depressing for more parts of Europe, with high and increasing rates of resistance to important antibiotics in common bacteria. So it was not surprising to see ECDC issue a corresponding press release focusing on worrying resistance to last-line antibiotics.

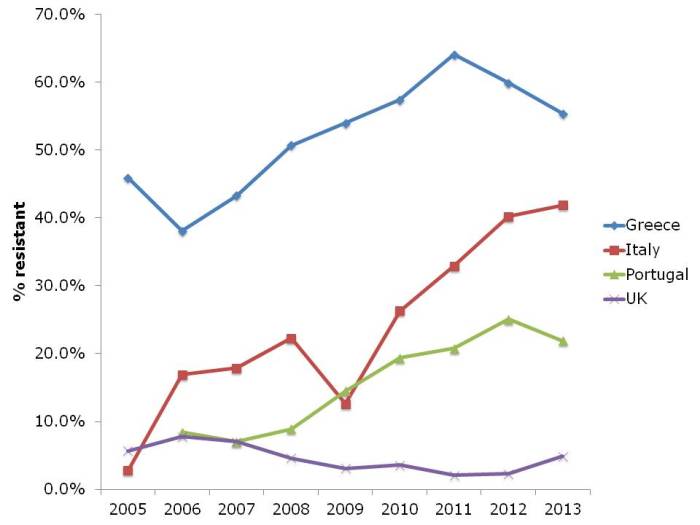

I’ve chosen a few illustrative countries from this useful interactive database. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae (i.e. CRE) is one of the most concerning challenges facing us right now. So it’s not good to see continued high rates of carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae in Greece, and the seemingly inexorable increase in Italy (Figure 1). It’s worth noting that these are invasive isolates, the majority of which would be bloodstream infections. And the mortality rate for a CRE bloodstream infection is around 50%…

Figure 1: Susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates to carbapenems

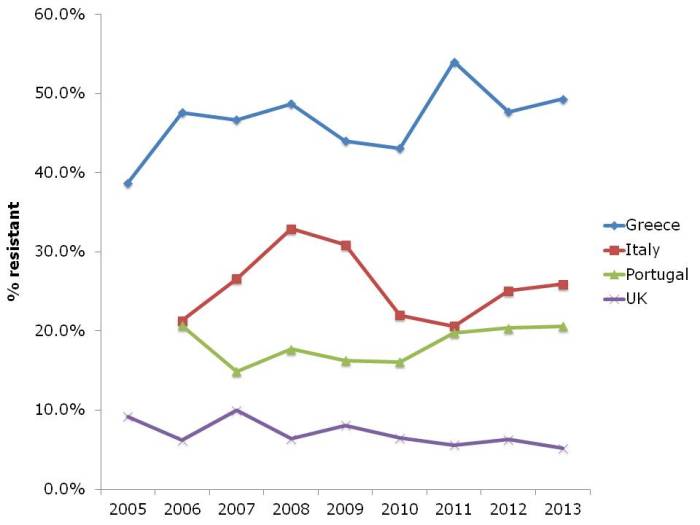

In some ways, the steady increase in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae from many parts of Europe, illustrated in Figure 2, is even more concerning than the sharp increases in CRE in some parts of Europe. If you draw a mental trend line for Italy and Portugal, it doesn’t look good.

Figure 2: Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates (resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides)

The picture for P. aeruginosa (and I suspect the other non-fermenters like A. baumannii, which isn’t included in EARS-Net) in terms of carbapenem resistance is different to the Enterobacteriaceae (Figure 3). Rates are high in Greece, intermediate in Italy and Portugal, and low in the UK. But the trend is stable.

Figure 3: Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasive isolates to carbapenems

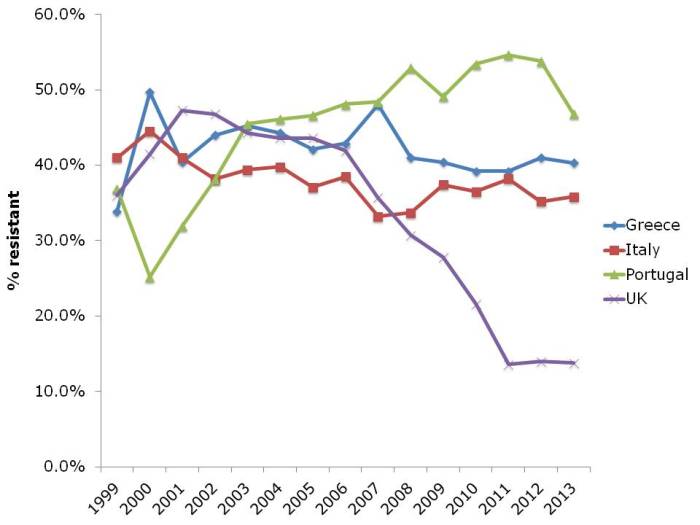

And let’s not forget about MRSA (Figure 4). The UK and some other European countries have done a tremendous job in reducing the transmission of MRSA. This has had an interesting and somewhat unexpected effect on the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus, which has also reduced considerably. I suspect this is a consequence of interrupting the transmission of MRSA, but failing to prevent the spread of MSSA. Put another way, if MRSA and MSSA fell in tandem, the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus would remain constant. The impressive reductions of MRSA reported in the UK have not been replicated everywhere in Europe. Portugal in particular increased from less than the UK in the early 2000s to more than the UK today. There is some evidence that the national campaign in Portugal to reduce healthcare-associated MRSA is making some impact, with a notable reduction in MRSA rate in 2013.

Figure 4: Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus invasive isolates to methicillin (i.e. MRSA rate)

In summary, it’s not all doom and gloom. The reductions in MRSA in the UK and elsewhere show that reducing the transmission of these antibiotic resistant bacteria can be done. But it takes considerable investment and national focus. Without this, it’s difficult to see the trends in antibiotic resistance, including to last-line agents, continuing to increase in some parts of Europe.

Filling the gaps in the guidelines to control resistant Gram-negative bacteria

I gave the third and final installment of a 3-part webinar series on multidrug-resistant Gram-negative rods for 3M recently. You can download my slides here, and access the recording here.

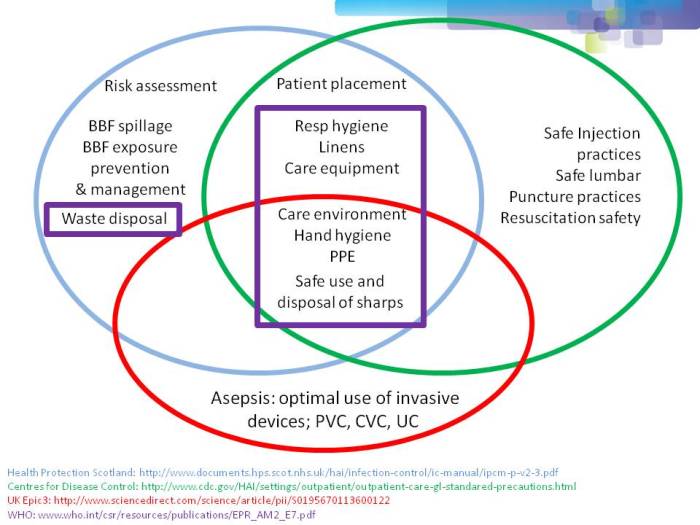

During the webinar, I provided an overview of the available guidelines to control CRE and other resistant Gram-negative bacteria. I then identified gaps in the guidelines, in terms of definitions of standard precautions, outbreak epidemiology and who should be on the guidelines writing dream team. Finally, I discussed some controversial areas in terms of effective interventions: patient isolation, staff cohorting and selective digestive decontamination.

One of the most important points when considering infection prevention and control guidelines is the issue of ‘standard precautions’. What do we apply to every patient, every time? As you can see from Figure 1 below, ‘standard precautions’ is far from standardized. This is problematic when developing and implementing prevention and control guidelines.

Figure 1: differences in the definition of ‘standard precautions’.

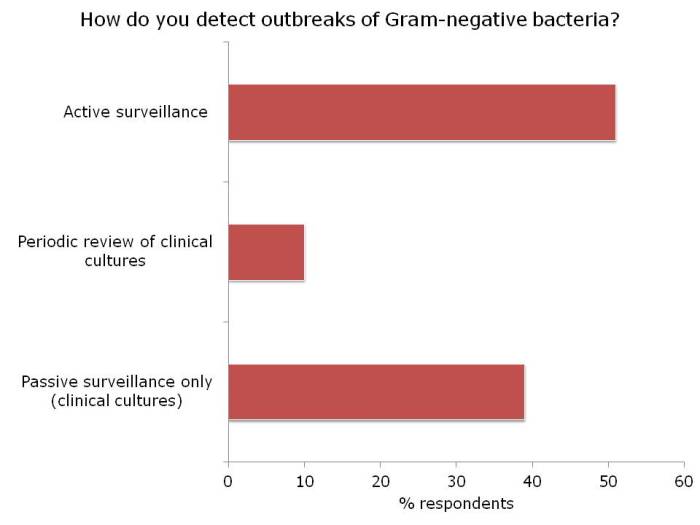

I had the opportunity to ask the webinar audience a few questions throughout the webinar, which are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: response to the questions from the 120 or so participants.

I was somewhat concerned but not that surprised that more than a quarter of the audience did not know where to access control guidelines for MDR-GNR. I suppose this means that we need to do a better job of signposting the location of the various guidelines available. Here’s a non-exhaustive list for starters:

- US CDC CRE Toolkit.

- US AHRQ CRE Toolkit.

- UK Public Health England CPE Tookit.

- UK ESBL guidelines.

- ECDC risk assessment on the spread of spreading (CPE).

- Canadian guidelines for carbapenem resistant GNB.

- Australian recommendations for CRE control.

- ESCMID MDR-GNR control guidelines.

There was a fairly even split between active and passive surveillance to detect outbreaks. The problem with relying on passive surveillance (i.e. clinical cultures) is that there’s a good chance that the ‘horse will have bolted’, and you have a large outbreak on your hands, before a problem is detected. For this reason, I favour active surveillance.

But who to screen? In the case of CRE, I was pleased to see that virtually nobody said nobody. There was a pretty even split between everybody, high-risk individuals or all individuals in high-risk specialties. Accurately identifying individuals who meet screening triggers is operationally challenging, as outlined by the “backlash” to the UK toolkit, so I think screening all patients in high-risk specialties (e.g. ICU) makes most sense.

So, what works to control MDR-GNR transmission? We don’t really know, so are left with a “kitchen sink” (aka bundle approach) (more on this in my recent talk at HIS). We need higher quality studies providing some evidence as to what actually works to control MDR-GNR. Until then, we need to apply a healthy dose of pragmatism!

Being bitten by antibiotic resistant CRAB hurts! (Acinetobacter that is.)

Guest bloggers Dr. Rossana Rosa and Dr. Silvia Munoz-Price (bios below) write…

In everyday practice of those of us who work in intensive care units, a scenario frequently arises: a patient has a surveillance culture growing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). While the ultimate course of action we take will be dictated by the patient’s clinical status, that surveillance culture, in the appropriate context, can provide us with valuable information.

For this study1, we looked at a cohort of patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit, and sought to identify the risk factors for CRAB infections. We found that patients who had surveillance cultures positive for CRAB had a hazard ratio of 16.3 for the development of clinical infections with this organism, compared to patient’s who remained negative on surveillance, even after adjusting for co-morbidities and antibiotic exposures. Since our results were obtained as part of a well-structured surveillance program, we know that colonization preceded infection. Unfortunately for some of our patients, the time from detection of colonization to development of clinical infections was a matter of days. With therapeutic options for the effective treatment of infections with CRAB limited to tigecycline and polymixins, the consequences of delaying therapy are often fatal. As described by Lee et al, a delay of 48 hour in the administration of adequate therapy for CRAB bacteremia can result in a 50% difference in mortality rate2.

Surveillance cultures are not perfect, and may not detect all colonized patients, but they can be valuable tools in the implementation of infection control strategies3, and as we found in our study, can also potentially serve to guide clinical decision that impact patient care and even survival.

Bio:

Dr. Silvia Munoz-Price (centre left) is an Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine at the Institute for Health and Society, Medical College of Wisconsin, currently serving as the Enterprise Epidemiologist for Froedert & the Medical College of Wisconsin. Dr. Rossana Rosa (centre right) is currently an Infectious Diseases fellow at Jackson Memorial Hospital-University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. She hopes to continue developing her career in Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control.

References

- Latibeaudiere R, Rosa R, Laowansiri P, Arheart K, Namias N, Munoz-Price LS. Surveillance cultures growing Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Predict the Development of Clinical Infections: a Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. Oct 28 2014.

- Lee HY, Chen CL, Wu SR, Huang CW, Chiu CH. Risk factors and outcome analysis of Acinetobacter baumannii complex bacteremia in critical patients. Crit Care Med. May 2014;42(5):1081-1088.

- Munoz-Price LS, Quinn JP. Deconstructing the infection control bundles for the containment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. Aug 2013;26(4):378-387.

Image: Acinetobacter.

Reflections from HIS 2014, Part III: Education, communication, and antibiotic resistance

Welcome to the third and final installment of my reflections from HIS 2014. You can access the ‘box set’ via the list at the start of Part I.

Prof Alison Holmes – Impact of organisations on healthcare-associated infection

Self-professed pragmatist Prof Holmes reminded us that the perceived and actual priorities of society, politicians and healthcare systems mean that it’s not all about infection control. We must harness macro (inter-hospital) and meso (inter-departmental) and micro (inter-team) relationships to successfully control transmission. This requires shared beliefs, reinforcement systems, role models, and the right staff skills. Plus, we need to get HCAI on the metric dashboard of CEOs. Indeed, HCAI outcomes are a sensitive surrogate marker of organisation performance, so this should be attractive to the hospital CEO once understood. We also need to embrace the public to tackle antibiotic resistance. Government messages about reducing antibiotic resistance have helped our day job (and proved popular on Twitter)! Involving patients and the public in our research makes everybody happy; patients and the public like it, and it improves our research (and helps to win grants). We need to embrace ‘mHealth’ in all its forms – games, apps and more – remembering that dinosaurs became extinct. The bottom line? Organisational, structural and managerial issues are crucial for the prevention of healthcare-associated infection (and the Lancet ID agrees).

Prof Herman Goossens – European Antibiotic Awareness Day

Since it was the occasion of European Antibiotic Awareness Day (EAAD) 2014, the talk from the impressive Prof Goossens was well timed! EAAD is a campaign aimed at the public and professionals to highlight the issues around antibiotic use and resistance. Many of the campaign materials are useful, including a toolkit for self-medication without antibiotics and various infographics. Prof Goossens spent some time discussing how to measure the impact of EAAD. A lot of questionnaire type surveys have been performed, and it does seem that EAAD has prompted a swing towards a better understanding of antibiotics, so well done to all involved.

What’s hot and what’s not in infection prevention and control?

Dr Jenny Child (JHI Editor) presented a view of the literature through the eyes of a journal editor! Bad research can do much damage: look no further than the MMR & autism debacle. Worth remembering that indifferent, uncitable papers will not get published; it’s just not in the journal’s interest. Also, clever, ‘pseudo-scientific’ language is a barrier to good science. The bigger the journal, the plainer the language. Finally, whilst JHI has traditionally been a quantitative medicine journal (with p values and 95% confidence intervals!), like it or not, social science is coming!

I gave a talk on ‘What’s trending in the infection prevention and control literature’. You can access the slides and recording on a separate blog, here. Finally, Dr Jim Gray (JHI Deputy Editor) scanned the horizon of the infection control literature, seeing studies with specific interventions and real clinical outcomes (not proxy measures), SSIs, antibiotic resistance (especially CRE), obesity, design & technology, diagnostics and decontamination!

Antibiotic stewardship: persuasion or restriction?

Esmita Charani began by explaining the need to achieve behaviour change, not education in isolation, in order to effectively moderate antibiotic prescribing behaviour. The local prescribing culture is likely to influence prescribing policy more than the national guidelines. Junior doctors often don’t have a clue what to prescribe, so it’s a case of follow-my-leader (i.e. consultant). But targeting hospital consults alone won’t get us out of the mess of antibiotic resistance. We need to engage a wider audience, including the public.

Meanwhile, Prof Inge Gyssens outlined the impact of antimicrobial restriction: contribute to MRSA reductions, prevent the emergence of MDR-GNR, and may help to bring outbreaks under control. The only downside is that switching to another antibiotic may cause more problems than it solves – a ‘squeezing of the balloon’ type effect. In a way, doctors are “addicted” to antibiotics. Put simply, antibiotic stewardship through restriction is a ‘cold turkey’ approach that works.

Although not a formal debate, Esmita Charani and Prof Gyssens did a good job of presenting both viewpoints. I was left concluding that both persuasion and restriction are important but when it comes down to it, restriction is more important than persuasion. Left to their own devices, antibiotic prescribers will sometimes make poor choices; restriction takes away that choice!

Summary

I really enjoyed HIS 2014 – especially the opportunity to contribute to the conference via my talk (on trends in the IPC literature) and poster round. The conclusion of my talk was to look into my crystal ball and highlight what will be trending by the time HIS 2016 comes around:

- I’m pretty certain that Ebola and MERS will not be trending (at least I hope not). However, the scars of Ebola in West Africa will take a generation to heal. There’s a chance that we could be experiencing the next Influenza pandemic, but it’s more likely we’ll be talking pandemic preparedness.

- Whilst I personally favour targeted interventions, I fear there will be a general move towards universal interventions. I also fear that the confusing ‘vertical’ (aka targeted) vs. ‘horizontal’ (aka universal) terminology will be widely adopted, despite the fact that it’s confusing!

- Faecal microbiota transplantation is only going to get bigger. It will be the standard of care for recurrent CDI by the time the next HIS conference comes around – perhaps even via oral ‘crapsules’.

- Whole genome sequencing will not be as trendy as it is right now – it will just be a standard tool that we all use.

- The trend of CRE (and other multidrug-resistant Gram-negatives) is only going to go one way – upwards!

- I’m hoping to see some high-quality studies (ideally cluster RCTs) of environmental interventions with clinical outcomes.

- Finally, as we all deal with increasing cost constraints, studies evaluating the cost-effeteness of infection prevention and control interventions are going to become increasingly important.

Tending the human microbiome

This isn’t hot off the press (a 2012 review article by Tosh & McDonald) but it’s probably more important now than when first published, given our rapid advances in understanding of the importance of the microbiome in human health over the last year or two.

A couple of clear principles emerge from the review:

- A happy, healthy human microbiome is characterized by diversity (both in terms of number of different species, and diversity within the species), and composed mainly of bacteria that we’re not familiar with – Fermicutes and Bacteroidetes).

- Antibiotics have a profound and sustained effect on the human microbiome (even those that are typically associated with no or few side effects). This results in a reduction in both diversity and change in composition, which is bad news for human health. In particular, this leave the gut more open to colonization with unwanted intruders aka antibiotic resistant bacteria.

The future of anti-infective therapy according to Tosh and McDonald is in:

(1) Developing and using more microbiome-sparing antimicrobial therapy. The idea of ‘selective digestive decontamination’ flies in the face of this objective.

(2) Developing techniques to maintain and restore indigenous microbiota. A lot of progress has been made here, for example, in the case of faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for the treatment of recurrent CDI.

(3) Discovering and exploiting host protective mechanisms normally afforded by an intact microbiome.

Rather than obliterate our microbiome with overuse of antibiotic “Atomic bombs”, we need to carefully tend individual and collective microbiomes in order to make them resistant to the increasing queue of antibiotic resistant colonizers!

Article citation: Tosh PK, McDonald LC. Infection control in the multidrug-resistant era: tending the human microbiome. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:707-713.

Image credit: Modified from ‘Mushroom cloud‘.

CRE and friends: Q&A

I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).

I gave the first in a three part webinar series for 3M last night, and you can download the slides here. Also, you can access the recording here (although you will need to register to do so).

- Aug 19: CRE and friends: what’s the problem and how to detect them?

- Sept 16: Not all resistant Gram-negative bacteria are created equal: Enterobacteriaceae vs. non-fermenters

- Oct 7: Filling the gaps in the guidelines to control resistant Gram-negative bacteria

The webinar was attended by >200 participants from across the US. I tried to outline the three pronged threat of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative rods (especially CRE) in terms of high levels of antibiotic resistance, stark mortality (for invasive disease) and the potential for rapid spread (including the prospect of establishing a community reservoir). Then, I gave an overview of the US and European picture in terms of CRE prevalence. Finally, I discussed the diagnostic challenges and options.

The most interesting part for me was the response to the questions that I threw out to the audience (see Figure below).

Figure: response to the questions from the 200 or so participants.

I was somewhat saddened but not especially surprised that the difference between CRE and CPE was not clear in the minds of most participants. I appreciate that this may be in part due to the fact that ‘CPE’ seems to be used more commonly in Europe than in the US. But this is an international problem, so we need to get our terminology straight in our globalised world.

It was encouraging to hear that most US hospitals have had no CRE, or only one or two cases. However, 11% of the participants see CRE regularly, with cases unconnected to outbreaks. This is a concern, and suggests that CRE has become established in these areas. Indeed, a recent study from 25 Southeastern US community hospitals reports a 5-fold increase in the prevalence of CRE since 2008, suggesting that CRE is becoming established in some parts of the US.

Most participants didn’t know which method was used by their clinical laboratory to detect CRE. I’m not sure whether or not this is a problem. You’d hope that laboratorians to know that they’re doing!

Q&A

The webinar included time for a Q&A from the audience, which covered the following:

- “How long to resistant Gram-negatives survive on surfaces?” This depends on which Gram-negative you’re talking about. Non-fermenters, especially Acinetobacter baumannnii, have remarkable survival properties measured in months and years. Enterobacteriaceae have a somewhat lower capacity to survive on dry surfaces, but it can still be measured in weeks and months, rather than hours and days.

- “How important is the environment in the transmission of resistant Gram-negatives?” Again, this depends on which Gram-negative you’re talking about. For A. baumannii the answer is probably “very important” whereas for the Enterobacteriaceae the answer is more like “quite important”.

- “What would you recommend for terminal disinfection following a case of CRE?” I would recommend the hospitals usual “deep clean” using either a bleach or hydrogen peroxide disinfectant, and consideration of using an automated room disinfection system. I would not be happy with a detergent or QAC clean; we can’t afford to leave an environmental reservoir that could put the next patient at risk.

- “Are antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria also likely to be resistant to disinfectants” There’s been a lot of discussion on this issue, but the short answer is no. I’d expect an antibiotic-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolate to be as susceptible to disinfectants as a corresponding antibiotic-susceptible isolate.

- “Should patients with CRE be left to the end of surgical lists, and are is special instrument reprocessing required?” There is no need to implement special instrument reprocessing – follow your usual procedures here. Should CRE patients be left to the end of surgical lists? It would be prudent if possible, but don’t lose sleep over it.

- “Are any special decontamination measures necessary for endoscopes?” A number of outbreaks of CRE have been reported associated with endoscopy. However, usual endoscope reprocessing methods should be sufficient to deal with CRE, provided they are done correctly!

- “How do you lessen your chances of acquiring CRE?” Healthy individuals lack the risk factors for CRE infection (although CRE can occasionally cause infections in the community). Thus, the personal protective equipment (PPE) specified for contact precautions (gloves and gowns) combined with rigorous hand hygiene are sufficient to protect healthcare workers.

- “Are toilet seats in India safe?” What a question! I guess we’re talking about an organism with gastrointestinal carriage, so it’s probably that contamination of the toilet seat will occur. It may be prudent to clean or disinfect toilet seats in India before using them. Either that, or squat!

- “Can you expand on isolation protocols?” Firstly, ensure that patients infected or colonized with CRE are assigned a single room (not so relevant in the US, but important in healthcare elsewhere). Then, make sure you have appropriate policy and supply of PPE (principally gloves and gowns). Consider implementing ‘enhanced precautions’, including a restriction of mobile devices. Finally, consider cohorting patients and staff to the extent possible. You can read more about NIH’s approach to isolation here.

- “Can patients who are colonized with CRE be deisolated?” This is a tricky one, which is basically an evidence free zone and hence an area of controversy. Longitudinal studies show that carriage of CRE can persist for months or even years, so it makes sense to continue isolation for the duration of a hospitalization and not bother with repeated swabbing. At the time of readmission, it makes sense to take a swab to see whether colonization continues. If not, then it may be rational to deisolate them – perhaps after a confirmatory swab. I wish I could be more decisive here, but the evidence is scant.

Do please let me know if you have anything to add to this Q&A!