Infected patients shed pathogens into the environment, resulting in increased risk of infection for the subsequent occupant of the room by a factor or two or more.1 For example, in one study, patients admitted to rooms previously occupied by patients with C. difficile infection (CDI) were 2.8 times more likely to develop CDI than patients admitted to rooms disinfected using conventional methods. Thus, most agree that more needs to be done to reduce contamination with C. difficile spores in order to interrupt transmission. However, what level of disinfection is required to prevent the transmission of C. difficile?

A consideration of data relating to the infectious dose of C. difficile is a useful first step. In hamster studies, Larson and Borriello showed that only one or two spores of C. difficile were sufficient to initiate infection in clindamycin-treated hamsters.2 This indicates that very low levels of C. difficile spores can initiate infection.

Lawley, et al.3 developed a murine model that provides useful background data on infectious dose. A dose-response relationship was established between the concentration of contamination in the cages and the proportion of healthy mice that developed CDI. All mice became infected when exposed to 100 spores/cm2 and 50 percent of mice became infected when exposed to 5 spores/cm2. The point at which none of the mice became infected was a concentration of less than one spore per cm2. The mice were exposed to the contaminated cages for one hour. In the healthcare environment, room exposure times are usually measured in days and so these estimates are likely to be conservative. Although translating data from animal models to meaningful clinical practice is difficult, it appears from these animal models that a low concentration of contamination is able to transmit spores to a susceptible host, as is the case with other healthcare-associated pathogens such as norovirus. 4

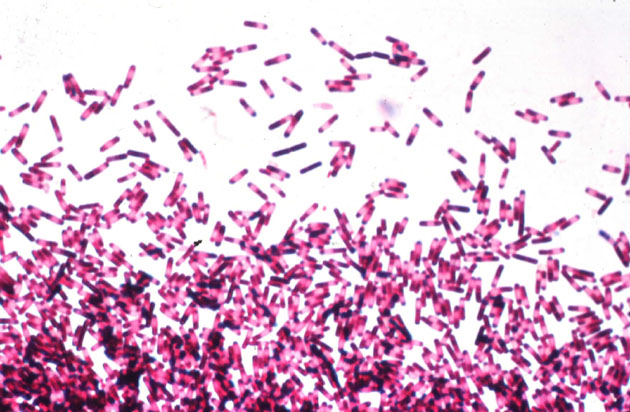

The low infectious dose of C. difficile is not the only challenge to disinfection. Bacterial endospores can survive on surfaces for many months5 and are resistant to several commonly used disinfectants.6 Patients with CDI result in widespread fecal contamination with C. difficile present in the feces of infected individuals at concentrations in excess of 106 spores per gram.7

Lawley, et al. examined which disinfectants were able to interrupt the transmission of C. difficile and established a relationship between the level of inactivation of C. difficile spores in vitro and the degree to which transmission was interrupted (figure).

Figure. Correlation between in vitro log reduction and interruption of transmission of C. difficile spores in a murine model.3

The oxidizing agents sodium hypochlorite (bleach) and hydrogen peroxide vapour (HPV) were the only agents tested that achieved a 6-log reduction on C. difficile spores in vitro and completely interrupted the transmission of C. difficile. Notably, both bleach and HPV disinfection can reduce the incidence of CDI in healthcare applications.8-9 Based on these findings, the CDC recommends that surfaces potentially contaminated with C. difficile spores should be disinfected using EPA-registered sporicidal agent (such as bleach) or sterilants.

Recent data highlight the fact that agents with in vitro efficacy may not effectively eradicate hospital pathogens from surfaces due to limitations with achieving adequate distribution and contact time using conventional cleaning methods.1,10 The emergence of ‘no-touch’ automated disinfection methods provide an alternative to reliance on a manual operator for the inactivation of pathogens on surfaces. HPV is an EPA-registered sterilant that achieves a 6-log reduction on C. difficile spores in vitro, eradicates C. difficile spores from surfaces and reduces the incidence of CDI and successfully mitigates the increased risk from the prior room occupant. 5, 9, 11-13

In summary, given the fact that a small number of C. difficile spores are sufficient to cause CDI in susceptible individuals, disinfectants with an EPA-registered sporicidal claim or sterilants should be used for disinfecting rooms used by patient with CDI. ‘No-touch’ methods, such as HPV, remove reliance on the operator to achieve adequate distribution and contact time and are appropriate for the terminal disinfection of rooms used by patients with CDI.

References:

1. Otter JA, Yezli S, French GL. The role played by contaminated surfaces in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidem. 2011; 32:687-99.

2. Larson HE, Borriello SP. Quantitative study of antibiotic-induced susceptibility to Clostridium difficile enterocecitis in hamsters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1990; 34:1348-53.

3. Lawley TD, Clare S, Deakin LJ, et al. Use of purified Clostridium difficile spores to facilitate evaluation of health care disinfection regimens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010; 76:6895-900.

4. Yezli S, Otter JA. Minimum infective dose of the major human respiratory and enteric viruses transmitted through food and the environment. Food Environ Microbiol 2011; 3:1-30.

5. Otter JA, French GL. Survival of nosocomial bacteria and spores on surfaces and inactivation by hydrogen peroxide vapor. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47:205-7.

6. Humphreys PN. Testing standards for sporicides. J Hosp Infect 2011; 77:193-8.

7. Al-Nassir WN, Sethi AK, Nerandzic MM, Bobulsky GS, Jump RL, Donskey CJ. Comparison of clinical and microbiological response to treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease with metronidazole and vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47:56-62.

8. Mayfield JL, Leet T, Miller J, Mundy LM. Environmental control to reduce transmission of Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31:995-1000.

9. Boyce JM, Havill NL, Otter JA, et al. Impact of hydrogen peroxide vapor room decontamination on Clostridium difficile environmental contamination and transmission in a healthcare setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidem. 2008; 29:723-9.

10. Manian FA, Griesenauer S, Senkel D, et al. Isolation of Acinetobacter baumannii complex and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus from hospital rooms following terminal cleaning and disinfection: Can we do better? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32:667-72.

11. Passaretti CL, Otter JA, Reich NG et al. An evaluation of environmental decontamination with hydrogen peroxide vapor for reducing the risk of patient acquisition of multidrug-resistant organisms. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 27-35..

12. Manian FA, Griesnauer S, Bryant A. Implementation of hospital-wide enhanced terminal cleaning of targeted patient rooms and its impact on endemic Clostridium difficile infection rates. Am J Infect Control 2012..

13. Cooper T, O’Leary M, Yezli S, Otter JA. Impact of environmental decontamination using hydrogen peroxide vapour on the incidence of Clostridium difficile infection in one hospital trust. J Hosp Infect 2011; 78:238-40.

The New England Journal of Medicine recently published an article evaluating the burden of CDI in the USA. The huge CDC-led initiative collected data from 10 geographically distinct regions, identifying more than 15,000 cases. Around two-thirds of cases were classified as healthcare-associated (although only 25% were hospital-onset). This means that, prima facie, a third of CDI cases were community-associated. I find this proportion difficult to believe: I strongly suspect that many of these cases would have had healthcare-associated risk factors if the team were able to look hard enough. For example, they used a fairly standard 12 week look-back period to evaluate previous hospitalisation, but how would the data look if they’d used 12 months? Also, it’s usually only possible to evaluate previous hospitalisation in a single healthcare system, but many patients commute between various healthcare systems. The authors acknowledge in the discussion that this designation of “community-acquired” may be inaccurate based on the finding from a previous study whether healthcare-associated risk factors were identified in most patients, but only be a detailed phone interview.

The New England Journal of Medicine recently published an article evaluating the burden of CDI in the USA. The huge CDC-led initiative collected data from 10 geographically distinct regions, identifying more than 15,000 cases. Around two-thirds of cases were classified as healthcare-associated (although only 25% were hospital-onset). This means that, prima facie, a third of CDI cases were community-associated. I find this proportion difficult to believe: I strongly suspect that many of these cases would have had healthcare-associated risk factors if the team were able to look hard enough. For example, they used a fairly standard 12 week look-back period to evaluate previous hospitalisation, but how would the data look if they’d used 12 months? Also, it’s usually only possible to evaluate previous hospitalisation in a single healthcare system, but many patients commute between various healthcare systems. The authors acknowledge in the discussion that this designation of “community-acquired” may be inaccurate based on the finding from a previous study whether healthcare-associated risk factors were identified in most patients, but only be a detailed phone interview.