Nosocomial or hospital-acquired infections are a worldwide problem affecting millions of patients yearly and increasing morbidity and mortality. The role of the hospital inanimate environment (environmental surfaces and surfaces of medical equipment) in the transmission of certain nosocomial pathogens such as C. difficile, norovirus, MRSA, VRE and Acinetobacter is now well established supported by various studies and publications. Most, if not all of these studies, investigated the transmission process in patient rooms or ICUs. Although the role of air in the transmission of pathogens has been extensively studies in the operating room (OR) setting, do contaminated surfaces play a role in pathogen transmission in the OR?

A recent review article published in the journal “Surgical Infection” questioned whether the OR inanimate environment contributed to the transmission of pathogens, hence possibly causing infections including surgical site infections (SSIs). Few studies have investigated surface contamination in the OR and even fewer have investigated possible pathogen transmission from the environment in this setting. While the inanimate environment in the OR has been considered a potential source for pathogens that may cause SSIs for more than 100 years, the role of this environment in the patient acquisition process within this setting is still debatable. Before revealing the conclusions of the review paper, I would like to look at both sides of the argument.

THE OR INANIMATE ENVIRONMENT DOES NOT PLAY A ROLE IN PATHOGEN TRANSMISSION AND INFECTION

The patient population and length of stay

In a hospital, patients colonised or infected may spend days or even months in ward rooms or ICUs increasing the chance that these patients will contaminate their environment or acquire pathogens from that environment. The likelihood of environmental contamination or pathogen acquisition increases with the length of hospital stay as well as other factors such as gross contamination and soiling.

In the OR setting however most patients spend only few hours under full or partial anaesthesia. This makes it less likely that these patients will contaminate their environment or acquire pathogens from the environment (by self inoculation at least). In addition, although gross contamination via blood for example is common, other type of gross environmental contamination linked to transmission such as diarrhoea and vomiting are less likely to occur in an OR.

The OR environment (surfaces and air)

Unlike most patient rooms, OR air quality is well regulated to prevent contamination via the air. This not only reduces the risk of infection via airborne pathogens but also reduces the amount of pathogens settling on and contaminating environmental surfaces in ORs. In addition, the OR inanimate environment is routinely cleaned/disinfected. Most ORs are cleaned at the end of the working day and many surfaces and areas are cleaned before and between surgeries with strict policies on how to deal with gross contamination (e.g. blood and tissue).

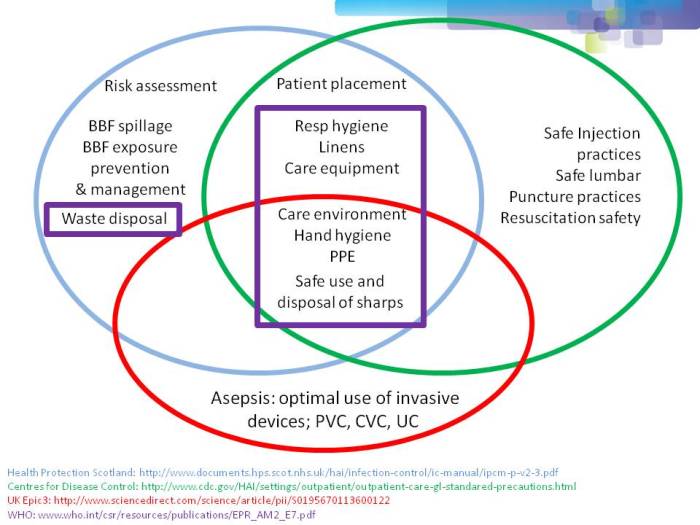

Minimising infection risk

As most SSIs are thought to originate from patients’ or healthcare personnel’s own flora, many interventions are in place in ORs to minimise the risk of contamination and infection. These include policies for hand scrubbing and disinfection, gloving, masks, and the proper preparation of patients’ skin before incision. The instruments used in surgery are also routinely sterilised before surgery to minimise the risk of infection.

Organisms involved in SSIs

The hospital environment has been implicated in the transmission of a number of pathogens including norovirus, C. difficile, MRSA, VRE and Acinetobacter. These pathogens are able to contaminate the environment at a high load and survive for long period of time facilitating transmission and acquisition. While infections with these organisms can be acquired in the OR, with the exception of Staphylococcus species, these pathogens are not the major causes of SSIs. The environmental resilience of other organisms involved in SSIs is not well characterised and it is unclear whether they can survive long enough in the environment to be transmitted.

THE OR INANIMATE ENVIRONMENT IS A SOURCE OF PATHOGENS THAT CAUSE INFECTION

The OR environment

ORs are busy, with many personnel involved during a surgical procedure, some of whom come and go in and out of the OR during the process. It is also an environment with multiple and frequent contact between personnel, patients and the environment including medical equipment. It is difficult if not impossible to observe the WHO’s 5 moments for hand hygiene in such an environment, or to clean and disinfect the environmental surfaces effectively during a surgical procedure. Organisms originating from the floor of the OR can also be disturbed by walking and are taken into the air which may increase the risk of infection.

The OR inanimate environment is contaminated

Many people in the general public think of ORs as ultra clean, even sterile, environments. For anyone working in ORs, it is clear that this view is far from the truth. Although modern ORs have strict measures to reduce contamination, the OR inanimate environment becomes contaminated with various organisms including those involved in SSIs. Studies have reported contamination of various OR areas such as anaesthesia equipment, beds, intravenous pumps and poles, computer keyboards, telephones and OR floors. A variety of pathogens capable of causing infections have been identified including Gram-negative bacilli such as Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas species, Staphylococcus including (MRSA) and Enterococcus. These results may be in part due to the fact that suboptimal cleaning in ORs is a widespread issue in hospitals.

Pathogen transmission occurs in ORs

A number of studies in ORs focusing on the role of anaesthesia equipment and providers in the contamination and transmission of pathogens in ORs have concluded that the hands of anaesthesia providers, patient IV tubing and the immediate patient environment were contaminated immediately before or during patient care with a wide range of bacterial pathogens leading to transmission. Transmission of pathogens from and to the hands of the anaesthesia providers involving the inanimate environment occurs frequently given the frequent contact with the environment in ORs.

Human behaviour in ORs contributes to environmental contamination and transmission

We are all familiar with the view that surgeons tend to be the worst healthcare workers as far as hand hygiene compliance is concerned. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg regarding lapses in infection prevention in ORs. For instance, anaesthesia provider’s behaviour and attitude including confusion on when and how often to perform hand hygiene during a procedure is a common cause of pathogen transmission. In one study, anaesthesia providers touched 1,132 objects during 8 hours of observations in OR, but only performed a total of 13 hand disinfections. No hand disinfections were witnessed at any time during 3 (43%) of the procedures observed. Furthermore, hand hygiene failed to precede or follow procedures, blood exposure or contact with the floor. Alarmingly, it has been reported that objects that fall onto the OR floors during surgery were frequently placed back either on to horizontal work surfaces or even on to the patients themselves during operations.

THE CONCLUSION

It is clear that the inanimate environment of the OR, including medical equipment, can become contaminated with pathogens that cause infections including SSIs. These pathogens can then be transmitted to the hands of healthcare workers and have the potential to cause infection. Further studies are necessary to quantify the role of contaminated surfaces in the transmission of pathogens and to inform the most effective environmental interventions in the ORs. Given the serious consequences of SSIs, special attention should be given to the proper cleaning and disinfection of the inanimate environment in ORs in addition to the other established measures to reduce the burden of SSIs. These include addressing the human behaviour that contributes to environmental contamination and transport of surface pathogens into the vulnerable sites of patients during surgery. Such measures include reducing human traffic in ORs, stricter adherence to the standard operating protocols during procedures, and compliance with proper hand hygiene and gloving. Specific hand hygiene guidelines tailored to OR personnel may be needed given the large number of hand contact events per hour in these settings.

Image: NIH Library.