Carbapenems are a class of beta-lactam antibiotic with a broad spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Whilst carbapenems are used for the treatment of Gram-positive infections, the emergence of Gram-negative bacteria with resistance to the carbapenem antibiotics is a health issue that has prompted unusually dramatic health warnings from the US CDC, Public Health England (PHE) and the European CDC (ECDC). However, the various acronyms employed to describe the subtleties of the problem are a minefield for the uninitiated:

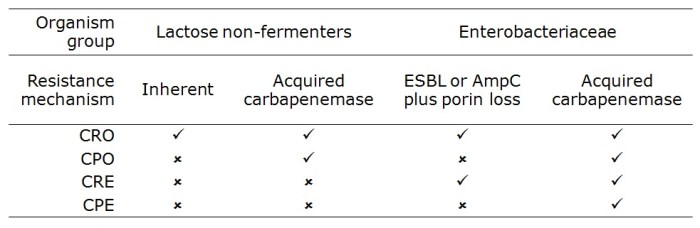

Carbapenem-resistant organism (CRO) – Gram-negative bacteria* including the Enterobacteriaceae (such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli) and non-fermenters (such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeroginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia) that are resistant to carbapenems by any mechanism. The non-fermenters can be inherently resistant to carbapenems, or they can acquire carbapenemases (typically KPC, VIM, NDM and OXA-48 types). Enterobacteriaceae do not have inherent resistance but may be resistant to carbapenems through the production of an acquired carbapenemase or the production of an ESBL or AmpC combined with porin loss.

Carbapenemase-producing organism (CPO) – Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermeters that are resistant to carbapenems by means of an acquired carbapenemase.

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) – Enterobacteriaceae that are resistant to carbapenems by any mechanism, including the production of an acquired carbapenemase or the production of an ESBL or AmpC combined with porin loss.

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) – Enterobacteriaceae that are resistant to carbapenems by means of an acquired carbapenemase.

The image below tries to graphically represent the relative size of these groups (not to scale!), and the table provides a summary of their distinguishing features:

“O” or “E”

The US CDC and European CDC seem to favour ‘CRE’ as a generic term for this problem, whereas the PHE in the UK seems to favour ‘CRO’. Clearly, each term has a defined meaning and context will determine which is technically correct. But which is most useful as a generic term?

The epidemiology of the non-fermenters and the Enterobacteriaceae is different, with the non-fermenters tending only to cause problems in very sick patients, usually in critical care settings. Meanwhile, the Enterobacteriaceae are more able to cause infections in a wider range of patients both inside and outside the hospital. Hence, the emergence of carbapenem resistance is more concerning in the Enterobacteriaceae, as demonstrated by rapid national and international spread of KPC-producing K. pneumoniae.

“R” or “P”

Amongst the Enterobacteriaceae, whilst carbapenem-resistance due to the production of an ESBL or AmpC combined with porin loss may lead to treatment failure, it is often unstable and may impose a fitness cost, meaning that these strains rarely spread. Hence, carbapenem resistance conferred by an acquired carbapenemases is the key problem.

So, for me, CPE would be the most suitable generic term for this emerging problem. However, since the US CDC and the ECDC seem to have gone with CRE, and the vast majority of CRE will be CPE, let’s go with CRE shall we?

[* Whilst Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to carbapenems (such as MRSA) could be described as ‘CROs’, these terms are reserved to describe Gram-negative bacteria.]