Another Infection Prevention Conference has been and gone; here are a few highlights. Worth noting that all of the submitted abstracts are published in an open access Journal of Infection Prevention supplement.

Opening talks

The now past-president Jules Storr kicked off the Conference with an inspiring talk on “real” leadership, which isn’t about CEOs and eminent professors. Real leadership inspires people to wash their hands in the dead of night when nobody’s looking. Roselinde Torres’ TED talk is worth a look (‘What it takes to be a great leader’) and ‘How to behave and why’ by the fantastically named Munro Leaf contains some leadership lessons from 1946!

Next up, IPS Patron Prof Didier Pittet challenged us to change our education methods to meet the changing (and dare I say somewhat fickle) needs of a rapidly changing world! Generation “We” (born 1980-2000, thus including me) require multimodal approaches to keep us engaged, and would probably rather watch a webinar than come to a conference! But, if you’d like to go ‘Old Skool’, there’s always Didier’s new book.

The highlight of the conference for me was Dr Jason Leitch’s address on developing a safety culture. A culture of safety has been embedded into other industries (e.g. airline, hotel and military) so why not healthcare? It’s a much quoted stat that a 747’s worth of people die from HCAI each [insert time period to suit your data]. So how many planes need to go down before we adopt a culture of safety? A culture of safety has a language to go with it – only the air traffic controller can say actually say “take-off”, and then only once. Perhaps only the IV nurse should be allowed to say “Catheter”, and only at the point of insertion!

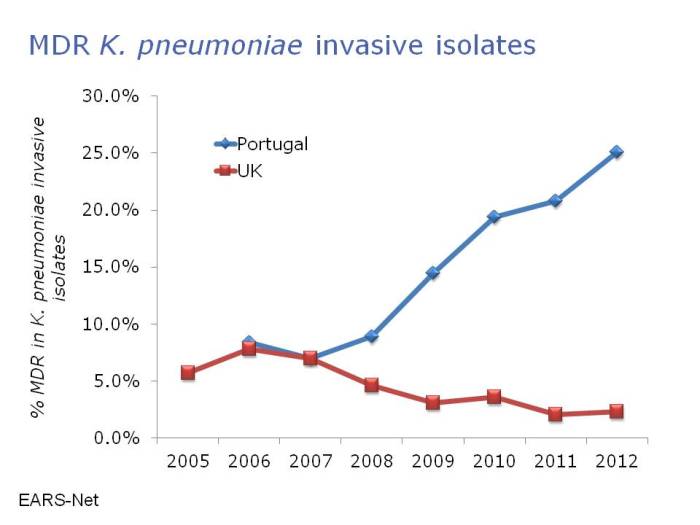

Dr Michael Borg then took to the stage to parallel antibiotic resistance with Star Wars: a battle of intergalactic scale! Michael spent some time discussing the impressive reductions achieved in his hospital on multidrug-resistant A. baumannii, applying the principles of the ESCMID guidelines, with a particular focus on environmental issues. However, the new and more challenging threat comes from the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae – aka the Death Star [note, pretty sure Dr Borg didn’t actually say that, but I think it’s a good fit with his analogy]. So what to do? Be an Ewok! Small and ostensibly insignificant, but surprisingly powerful as a collective force.

Cotteral Lecture – Dr Evonne Curran

Dr Evonne Curran delivered the Cotteral Lecture, entitled “The times they are a changing”. Reflecting on her thorough reviews of some older literature to write her outbreak columns on MRSA and CRE, Evonne reminded us how far we’ve come but how far we have yet to go. It wasn’t so long ago that we were questioning whether C. difficile was infectious (and now we’re asking a similar question from a different angle)! Equally, in 1990, installing one sink on a ward increased the number of sinks by 100%. Yet there can be no cause for complacency: we haven’t reached base camp for the CRE epi curve! Evonne didn’t quite finish on a song, but she did finish on a Hand Hygiene Haiku:

‘Five moments for hands

For infection prevention

Essential for all’

Universal gloves and gowns

Dr Dev Anderson (Duke) gave an engaging lecture on the impressive ‘Benefits of Universal Gloves and Gowns’ (BUGG) study. This cluster randomized controlled trial design is likely to be the gold-standard assessment of infection prevention and control interventions. The problem with this powerful design is that studies need to be large to be powered appropriately. This study involved 20 ICUs and still failed to meet the primary end point (a reduction in MRSA / VRE acquisition). So will ICUs around the world be switching to universal gloves and gowns? On the basis of this study, combined with the well-publicized downsides of “contact precautions”, no. A targeted approach to contact precautions is better…

As if to reinforce the message of judicious use of gloves, Jennie Wilson’s talk highlighted that using gloves badly is worse than not using gloves at all! Some of the staff perceptions surrounding glove use were enlightening, including the classic: “when I wear gloves, I don’t need to wash my hands as often”. Hmmm.

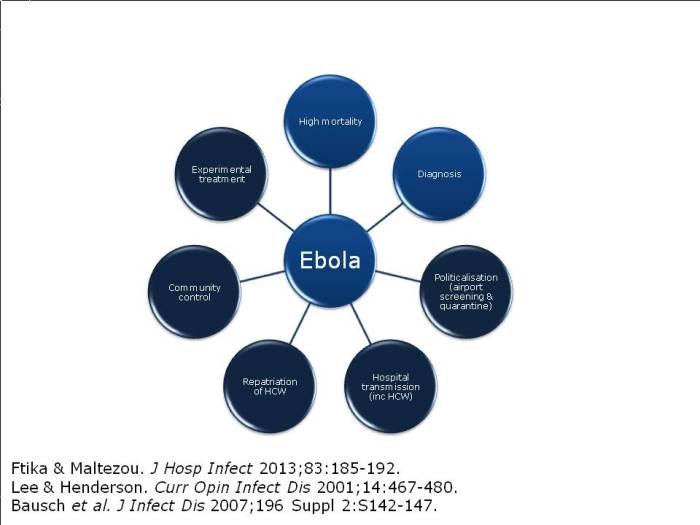

CRE stream

Or should I say CPE stream? Or perhaps CPC is more to your fancy? This excellent stream kicked off with Dr Bharat Patel assisting in us in navigating the ‘acronym minefield’ that is multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. An informal poll of the audience prior to Dr Patel’s talk suggested that only a handful would be comfortable explaining the difference between CRE and CPE to a colleague. Hopefully, this was remedied by the talk!

Then, Dr Tara Palmore (NIH, USA), Dr Andrew Dodgson (Manchester) and Erika Grobler & Ogra Marufu (King’s College Hospital, London) provided a series of ‘views from the trenches’ of CRE prevention and control. Dr Palmore described the fascinating utility of whole genome sequencing to dissect the outbreak more or less in real time. She also highlighted the use of ‘monitors’ whose sole job it was to ensure compliance with hand hygiene and PPE at room entry and exit! Dr Dodgson described the ongoing CRE problems in Manchester. My key message from Dr Dodgson was not to bother with contact screening when you identify a new case: just go ahead and screen the whole ward – more than once. Finally, Erika and Ogra gave their perspective on control challenges. They are now screening all paediatric admissions to their hospital for CRE carriage, which is not a popular or easy policy, but they consider it to be a cornerstone of effective control. As we all wrestle to implement the principles of the Toolkit, this session provided useful advice from those in the know.

Oral presentations

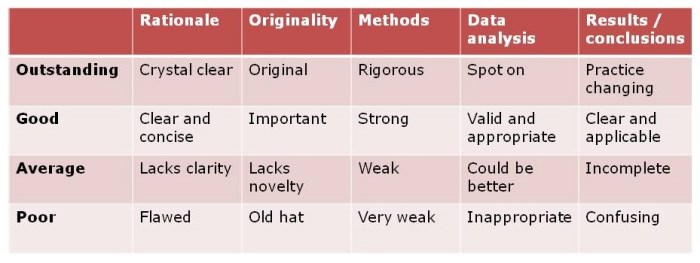

I didn’t make it to all of the oral presentations, but I was impressed by the ones that I saw. (Remember, you can view all of the accepted abstracts from the submitted oral and poster presentation in the Journal of Infection Prevention supplement.)

- Donald Bunyan: E. coli bacteraemia in Scotland: nearly 50% classified as “community”; but how many of these were frequent fliers?

- Angela Beal: Pulsed-xenon UV (Xenex): good reduction in total aerobic count, but less effective out of line of sight & 39% of sites VRE contaminated after process. Is this satisfactory?

- John Chewins: spraying aqueous oxygen peroxide (aka ozone) onto chronic wounds less likely to withdraw from RCT due to infection and improves patient’s quality of life scores.

- Jo Keward: introduction of semi-permanent Pods reduces missed isolation days by 60% on the Alder Hey HDU.

- Andrea Whitfield: Service User Involvement in HCAI research: A necessary evil to get your grant or vital for top class research?

Use of disinfectants and HCAI – Dr David Weber

Dr Weber began by reviewing the compelling data that contaminated surfaces contribute to the transmission of some hospital pathogens. An age-old question is whether contamination of hands or surfaces is more important in transmission. A recent modeling study helps to answer this, suggesting that hands are generally more important, but that this will depend on pathogen and setting. Getting the best out of hospital cleaning and disinfection is a simple equation: ‘Product + Practice = Perfection’. The problem is the ‘practice’ part of that equation; it’s difficult to assure process repeatability. This is where new technologies such as automated room disinfection systems, and antimicrobial surfaces can come in most handy. Finally, Dr Weber pointed us towards the AJIC and ICHE recent special editions on all things environmental.

Ayliffe Lecture – Dr Stephanie Dancer

Dr Stephanie Dancer began the Ayliffe Lecture by reiterating a wish that I had earlier in the conference: for genetically modified visible microbes on surfaces! That way we’d all be able to see the long survival and low infectious dose exhibited by many hospital pathogens. As we come towards the end of antibiotics, we need to move from cure to prevention. Remember, mortality due to S. aureus bloodstream infection was once 80% and may be so again as we lose more antibiotics. We need intervention bundles (aka ‘intervention umbrellas’) but not all solutions are possible, practical, affordable or acceptable. A good dose of evidence and common sense is required to find and implement interventions that work!

The BIG debate: universal vs. targeted interventions (Dr Gould vs. Dr Otter)

I think that Dr Gould and I achieved our purpose of presenting both sides of the debate without coming to physical blows. I found myself on uncomfortable ground arguing for a “No” vote in Glasgow following the Scottish “In/Out” referendum. I think my decision to wear a bow tie (see image below) in recognition of Dr Gould’s signature neck-wear lightened the mood!

Figure: My choice of neck wear

I’ve laid my arguments for targeted interventions out in a separate blog, but in short, universal interventions are appealing but fail to demonstrate short-term, long-term and cost-effectiveness. Targeted interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing transmission, preserve the activity of our precious antimicrobial agents, require less modification of human behaviour, and are cheaper and less resource-intensive. So, on balance, I favour targeted interventions for infection prevention and control.

Closing talks

Rose George gave an engaging talk ‘examining the unmentionables’. It’s eye-opening to think that 40% of the world population lacks adequate sanitation; open defecation is all too common with no privacy, dignity or safety! The flushing toilet, believe it or not, was voted the biggest medical advance of the last 200 years by the BMJ. Investing in sanitation makes financial sense too, with $1 invested in sanitation yields $6. You can see Rose’s TED talk here.

IPS Patron Tricia Hart and incoming president Heather Loveday rounded off the conference, exhorting us to examine our attitude and approach to infection and control. I left the conference feeling that IPS is in good hands with Heather at the helm.