My last post on Omicron was on 22/12/2021, 15 days ago, which seems like a lifetime ago! Back then, there was a great deal of uncertainty about how Omicron would manifest clinically, and how this would translate into hospitalisations and deaths. We now known more, but there is still considerable uncertainty. The latest technical briefing from UKHSA provides additional epidemiological updates. And the latest ONS study on prevalence in the UK gives us some eye-watering figures: in the week ending 31/12/2021, 1 in 25 people in England were infected with COVID-19, and 1 in 15 people in London. There’s a lot of it about. Overall, the outlook is looking better, but it’s going to be a very bumpy ride for those working in healthcare over the next month or so.

Continue readingepidemiology

What is the evidence for droplet transmission for SARS-CoV-2?

A guest post from Dr Evonne Curran…

The disputed airborne mode of transmission in this pandemic requires further scrutiny. Researchers have thus far focused on presenting a case for airborne transmission1 rather than disputing that the ‘primary’ mode of transmission for SARS-CoV-2 is via droplets2.

Continue readingOmicron: buckle up for a bumpy ride

I’ve been meaning to write an update on the Omicron variant of concern for a few weeks’ now and it’s now or never, so here we go! The Omicron variant has a host of mutations compared with previous variants, which seems to have given it the ability to spread much more rapidly. This may well be due in part to the ability to side-step antibody mediated immunity obtained through previous infection and vaccination. Omicron is spreading rapidly in the community. We don’t yet know what impact the current rapid community spread will have on hospitalisations and ultimately deaths, so time will tell.

Continue readingB.1.617.2: an update

PHE released the latest epidemiological summary of the B.1.617.2 VOC (aka “the variant that was first identified in India”) a few days ago. Evidence is emerging rapidly, and the datasets are far from conclusive. But it now seems clear that B.1.617.2 is more transmissible, causes no more hospitalisation or mortality, and vaccine effectiveness is slightly reduced when compared with other variants.

Continue readingThe Indian variant…

As you may have heard, there’s a new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern (VOC) on the block. So what do we know about this new variant? And how much of a threat does it pose to the pre-COVID freedom that we can see on the near horizon?

Continue readingThe role of ventilation in preventing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2

I gave a talk at the Sussex Infection Prevention Development Week yesterday on ventilation and preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. I learnt a lot in putting together the talk, so thought I’d share my slides (here) and some of the key points. Ventilation is a crucial way to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (and other respiratory viruses), and I hope that improved ventilation in health and social care settings will be one of the good things to come out of this pandemic.

Continue readingSARS-CoV-2 variant: an update

PHE have published a rapid epidemiological comparison of the SARS-CoV-2 variant (VOC 202012/01 aka B1.1.7) with ‘wild-type’ SARS-Cov-2 in this country. Most of the characteristics don’t look to be different – the variant is not associated with more hospitalizations or an increase in 28-day mortality. However, there does seem to be an increase in secondary attack rates of the variant compared with wild-type SARS-CoV-2.

Continue readingThe new COVID-19 variant: a primer

Unless you have been living under a rock, you’ll have seen that there’s a new COVID-19 variant on the scene. This block summarises the key information that has emerged so far about this new variant. It seems to be more transmissible, no more virulent, and there’s no evidence that the vaccines that are approved or nearly approved will be less effective against the variant.

Continue readingSecondary attack rate of COVID-19 in different settings: review and meta-analysis

A rather beautiful review and meta-analysis by colleagues at Imperial College London examines the evidence around the secondary attack rate (SAR) for SARS-CoV-2 in various settings, highlighting the risk of prolonged contact in homes as the highest risk for transmission.

Continue readingSARS-CoV-2 incubation period: where does the 14 days come from?

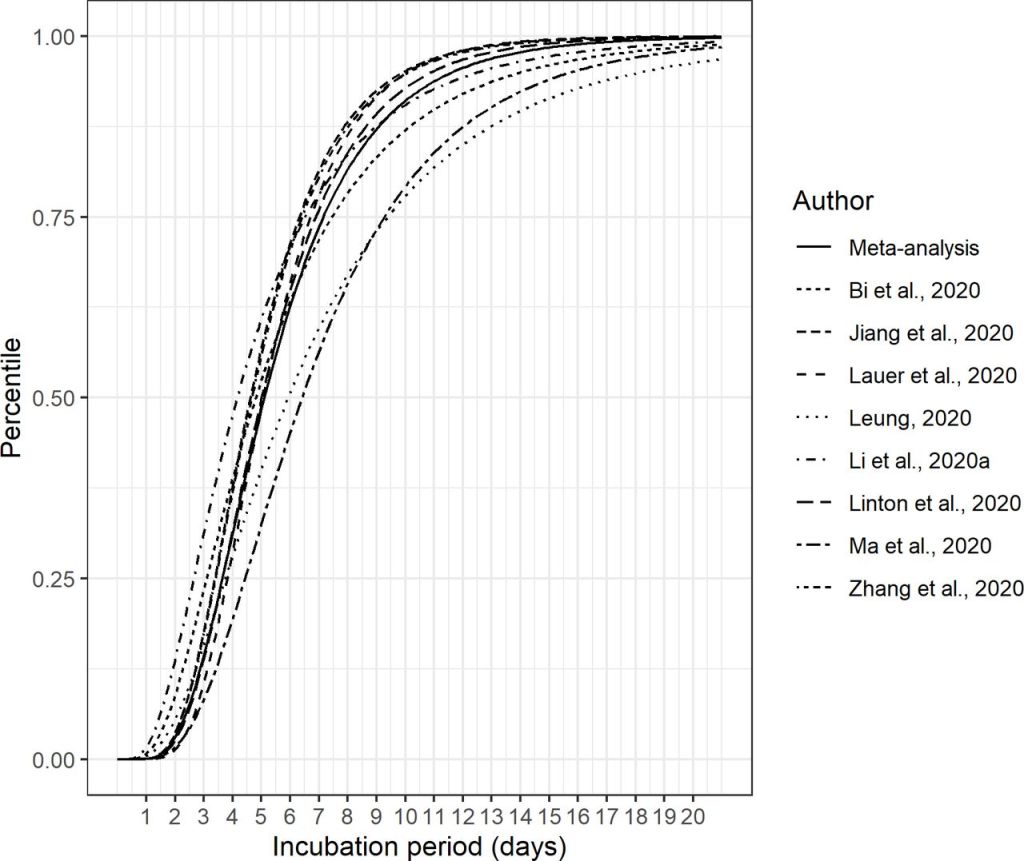

If you’ve had to self-isolate for 14 days following a possible exposure to somebody with COVID-19, you’ll relate to just how long it feels. Towards the start of the pandemic, the Otter family entered a 14 day household self-isolation due to COVID-like symptoms in the pups. At that time, mass testing was not available and so we’re left hanging to this day as to where or not it was or wasn’t. But where does the 14 days come from? And how does the probability of developing COVID-19 following exposure change over time? I was asked this yesterday, and came across a very hand review and meta-analysis of studies related to the SARS-CoV-2 incubation period.

The review includes, published in BMJ Open, includes nine studies in the meta-analysis. Overall, the median incubation period was 5.1 days, and the 95% percentile was 11.7 days (see the Figure below). The team recognise that things will change as new studies come along, so helpfully have published an R Shiny app that will be updated as new data is published. Quite a clever trick, although the Shiny app isn’t the most intuitive.

In answer to your specific question about the difference in risk on day 10 vs. day 14 following exposure, this is tricky and will depend on a number of factors. However, the risk of developing COVID from the point of exposure changes over the 14 days peaking around day 4/5. I’ve attached a systematic review and meta-analysis of the COVID incubation period. Figure 5 is probably most helpful, which shows from the meta-analysis of 8 studies that approx. 90% of individuals who would eventually test positive had tested positive by day 10, whereas >95% had tested positive by day 14.

International guidelines recommend an isolation period of 14 days following patient or staff exposure to COVID-19 (see PHE and CDC). So why 14 days? And not 13 or 16? As you can see, the odd person developed COVID-19 outside of the 14 day window since exposure, but this is uncommon. And I think there’s something pragmatic about 14 days being 2 weeks!