We know that many vegetive bacteria can survive on dry surfaces for longer than you might think. For some Enterococcus species, this capability is nothing short of extraordinary. In one study, Enterococcus dried onto a surface was still viable 4 years (yes FOUR YEARS) later! How can this be? No nutrients, no water (other than ambient humidity), and not an endospore former. A recent paper in the JHI may have some answers: Enterococcus is able to form dry surface biofilms and these contain viable Enterococcus many months after inoculation, regardless of species and substrate.

Continue readingBiofilm

Biofilms…the gift that keeps on giving!

Last week I spent some time at the Infection Prevention Society (IPS) annual conference in Birmingham which provided a fantastic selection of talks and discussions on current and emerging IPC challenges. One topic which came up time and time again was biofilms…. for example, whether the presence of biofilms provide Candida auris with the ability to persist in the clinical environment for prolonged periods, through to the role of biofilms in reduced susceptibility to disinfectants and antibiotics. It made me revisit an excellent recent review published in Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, which is the topic of today’s blog and tomorrow’s IPC Journal Club (register here).

Continue readingBeware Biofilms!

Have you ever wondered how on earth vegetative bacteria can survive on dry surfaces for years? Or why when you have an outbreak and you swab the environment you don’t find the outbreak strain even though you’re pretty sure it’s there? Or why a disinfectant that gets a 4-log reduction in the lab can’t eliminate a couple of hundred cfu of bacteria from a dry surface? Dry surface biofilms could be the answer to all these questions! I was involved in a multicentre survey of dry biofilms from across the UK, and we identified dry surface biofilms on 95% of the 61 samples there were tested. Worryingly, viable MRSA was identified on 58% of the surfaces! We need to think carefully about how much of a risk dry surface biofilms present, and whether we need to do more to tackle them.

The Trojan Horse

I’ve been mulling over the issue of sinks in clinical areas a lot recently and a paper published today in the Journal of Hospital Infection has really crystallised my thoughts. Sinks are everywhere; often extra ones are installed in the quest for high hand hygiene compliance however are we really thinking about the risks that these may cause apart from the traditional ones posed by Pseudomonas and Legionella? Do we even really reflect upon what they are used for? Continue reading

I’ve been mulling over the issue of sinks in clinical areas a lot recently and a paper published today in the Journal of Hospital Infection has really crystallised my thoughts. Sinks are everywhere; often extra ones are installed in the quest for high hand hygiene compliance however are we really thinking about the risks that these may cause apart from the traditional ones posed by Pseudomonas and Legionella? Do we even really reflect upon what they are used for? Continue reading

Preventing UTI: Could probiotics help?

A study protocol has caught my eye this week, a trial of oral probiotics vs placebo as prophylaxis for UTI in spinal cord patients, a very high risk group for these infections and associated complications. It will be a multi-site randomised double-blind double-dummy placebo-controlled factorial design study running over 24 weeks conducted in New South Wales, Australia. Probably about as robust as it gets scientifically. Continue reading

A study protocol has caught my eye this week, a trial of oral probiotics vs placebo as prophylaxis for UTI in spinal cord patients, a very high risk group for these infections and associated complications. It will be a multi-site randomised double-blind double-dummy placebo-controlled factorial design study running over 24 weeks conducted in New South Wales, Australia. Probably about as robust as it gets scientifically. Continue reading

Biofilms make the hospital environment far from ‘inanimate’

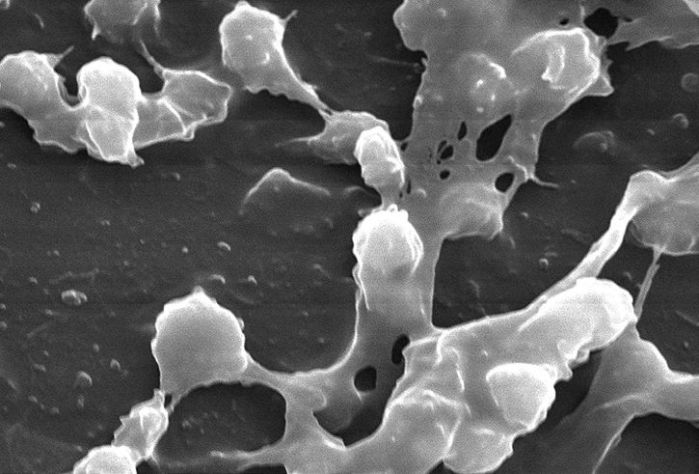

Anybody doubting that biofilms really do exist on dry hospital surfaces needs to read this study: biofilms are there, they are complex, and they are common. A landmark study by the same Australian Vickery group published in 2012 first identified biofilms on a handful of dry hospital surfaces in an ICU. But this study is far more comprehensive and convincing.

Do biofilms on dry hospital surfaces change how we think about hospital disinfection?

An important paper published in the Journal of Hospital Infection has identified biofilms on dry hospital surfaces. Biofilms are known to be important in several areas of medicine including indwelling medical devices and endoscope tubing, usually associated with surface-water interfaces. However, it was unclear whether biofilms formed on dry hospital surfaces. The study by Vickery et al. ‘destructively sampled’ several hospital surfaces after cleaning and disinfection using bleach (i.e. cut the materials out of the hospital environment and took them to the lab for analysis). Scanning electron microscopy was used to examine the surfaces for biofilms, which were identified on 5/6 surfaces: a curtain, a blind cord, a plastic door, a wash basin and a reagent bucket. Furthermore, MRSA was identified in the biofilm on three of the surfaces.

Could it be that we have missed or underestimated the importance of biofilms on dry hospital surfaces? Biofilms could explain why vegetative bacteria can survive on dry hospital surfaces for so long, be part of the reason why they are so difficult to remove or inactivate using disinfectants (bacteria in biofilms can be 1000x more difficult to kill than corresponding planktonic bacteria) and explain to some degree the difficulty in recovering environmental pathogens by surface sampling.

Biofilms are clearly not the only reason for failures in hospital disinfection given the difficulty in achieving adequate distribution and contact time using manual methods, but these findings may have implications for infection control practices within hospitals and on the choice of the appropriate disinfectants used to decontaminate surfaces.

Article citation: Vickery K, Deva A, Jacombs A, Allan J, Valente P, Gosbell IB. Presence of biofilm containing viable multiresistant organisms despite terminal cleaning on clinical surfaces in an intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect 2012; 80: 52-55.

Image courtesy of the Lewis Lab at Northeastern University. Image created by Anthony D’Onofrio, William H. Fowle, Eric J. Stewart and Kim Lewis