The ECDC recently released their 2013 report, which includes 2013 data. The data are on the whole fairly depressing for more parts of Europe, with high and increasing rates of resistance to important antibiotics in common bacteria. So it was not surprising to see ECDC issue a corresponding press release focusing on worrying resistance to last-line antibiotics.

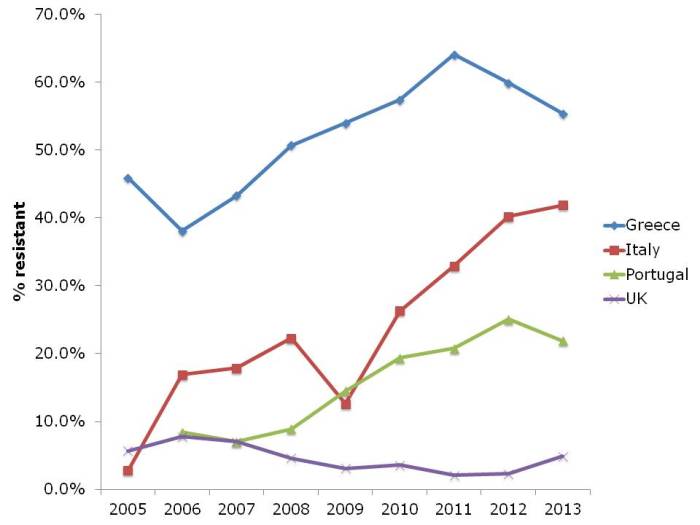

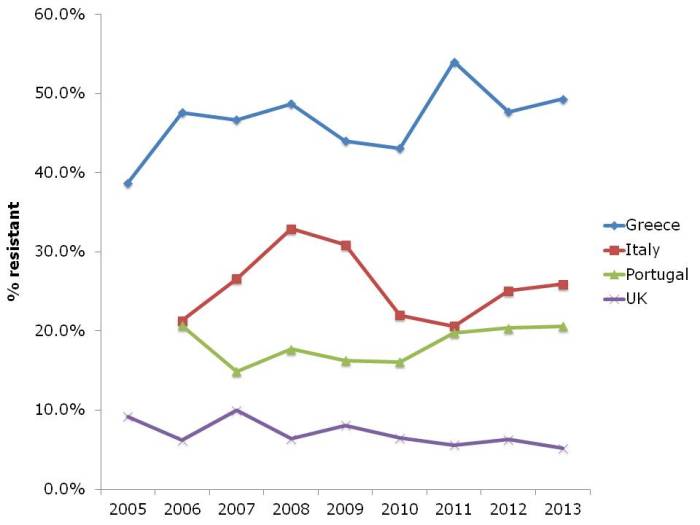

I’ve chosen a few illustrative countries from this useful interactive database. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae (i.e. CRE) is one of the most concerning challenges facing us right now. So it’s not good to see continued high rates of carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae in Greece, and the seemingly inexorable increase in Italy (Figure 1). It’s worth noting that these are invasive isolates, the majority of which would be bloodstream infections. And the mortality rate for a CRE bloodstream infection is around 50%…

Figure 1: Susceptibility of Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates to carbapenems

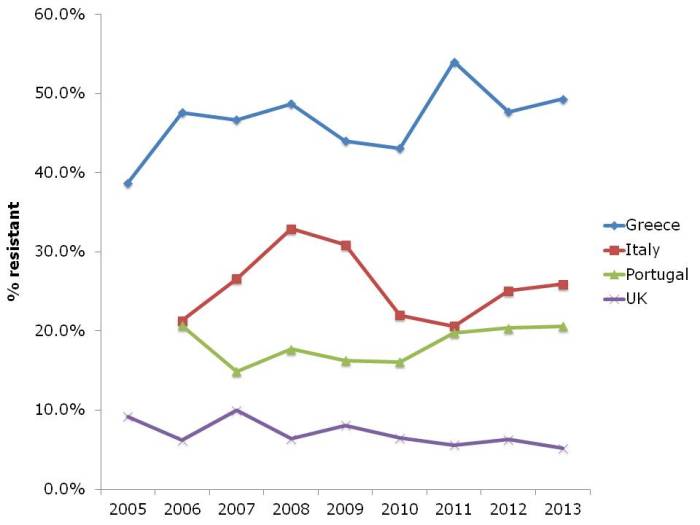

In some ways, the steady increase in multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae from many parts of Europe, illustrated in Figure 2, is even more concerning than the sharp increases in CRE in some parts of Europe. If you draw a mental trend line for Italy and Portugal, it doesn’t look good.

Figure 2: Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae invasive isolates (resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides)

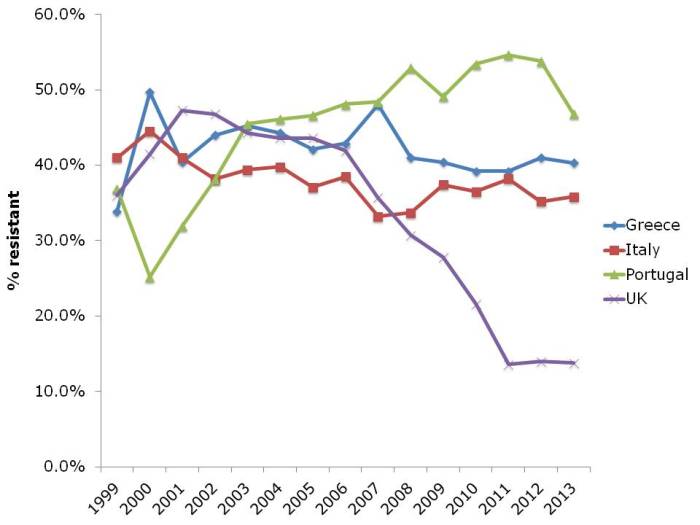

The picture for P. aeruginosa (and I suspect the other non-fermenters like A. baumannii, which isn’t included in EARS-Net) in terms of carbapenem resistance is different to the Enterobacteriaceae (Figure 3). Rates are high in Greece, intermediate in Italy and Portugal, and low in the UK. But the trend is stable.

Figure 3: Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasive isolates to carbapenems

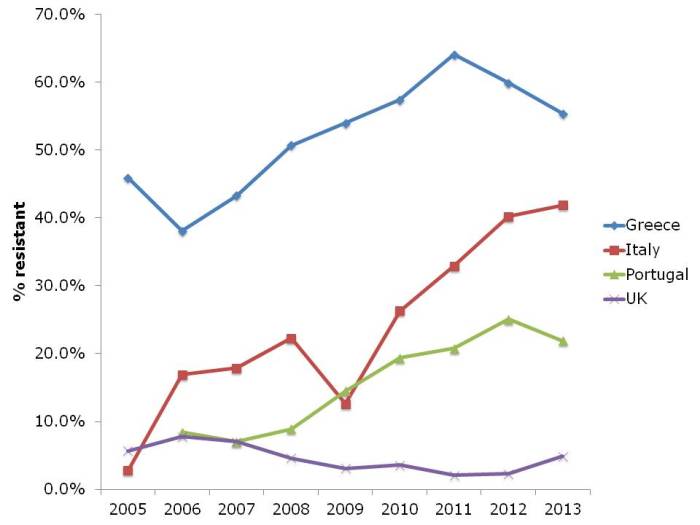

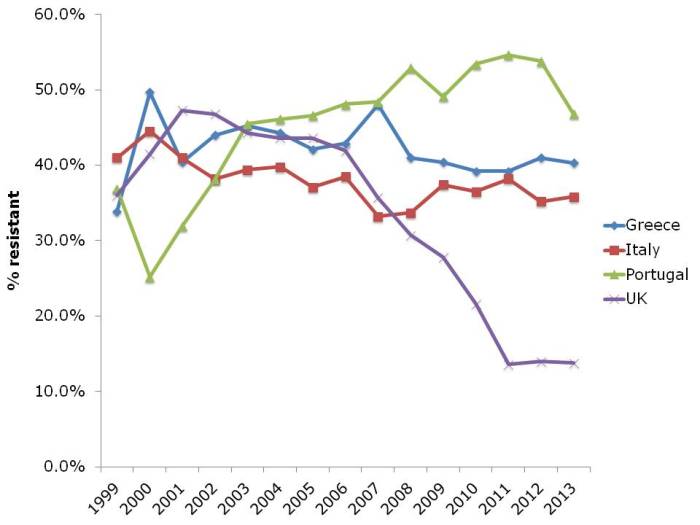

And let’s not forget about MRSA (Figure 4). The UK and some other European countries have done a tremendous job in reducing the transmission of MRSA. This has had an interesting and somewhat unexpected effect on the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus, which has also reduced considerably. I suspect this is a consequence of interrupting the transmission of MRSA, but failing to prevent the spread of MSSA. Put another way, if MRSA and MSSA fell in tandem, the rate of methicillin-resistance in S. aureus would remain constant. The impressive reductions of MRSA reported in the UK have not been replicated everywhere in Europe. Portugal in particular increased from less than the UK in the early 2000s to more than the UK today. There is some evidence that the national campaign in Portugal to reduce healthcare-associated MRSA is making some impact, with a notable reduction in MRSA rate in 2013.

Figure 4: Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus invasive isolates to methicillin (i.e. MRSA rate)

In summary, it’s not all doom and gloom. The reductions in MRSA in the UK and elsewhere show that reducing the transmission of these antibiotic resistant bacteria can be done. But it takes considerable investment and national focus. Without this, it’s difficult to see the trends in antibiotic resistance, including to last-line agents, continuing to increase in some parts of Europe.