I’ve written this post in preparation for tomorrow’s Journal Club, which will be about this paper on S. aureus colonisation and SSI (register here). Having not written or reviewed much on S. aureus for quite a while, I’m reading my second S. aureus paper in two weeks, following last week’s blog on a paper from the Healthcare Infection Society special on “MRSA: the enduring foe“!

Why I chose this article:

- S. aureus causes around 30% of SSIs.

- SSIs can affect up to 20% of surgical procedures in some categories.

- Each SSI often has significant impact on the patient journey, inpatient stay, antimicrobial usage, and financial costs (estimated in the region of £15,000 per SSI). There is also a measurable carbon impact for each SSI.

- Whilst we know that nasal colonisation with S. aureus is an important risk factor for SSI, this study explored in more detail the role of bacterial load, and impact of which body sites are colonisated on the risk of SSI.

Design and methods:

- The study used a dataset from the ASPIRE-SSI study, which was a prospective was a prospective observational cohort study in which adult surgical patients were included and followed from surgery up to 90 days after surgery to evaluate the role of S. aureus in SSI. The headline finding from the ASPIRE-SSI study is that S. aureus carriers are >4x more likely to develop an S. aureus SSI or BSI compared with non-carriers.

Key findings:

- The S. aureus colonisation rate was 67% of the 5,004 patients included. This is much higher than you’d expect – perhaps because the study did not require confirmatory lab tests for S. aureus aside from colony colour / morphology on chromogenic agar.

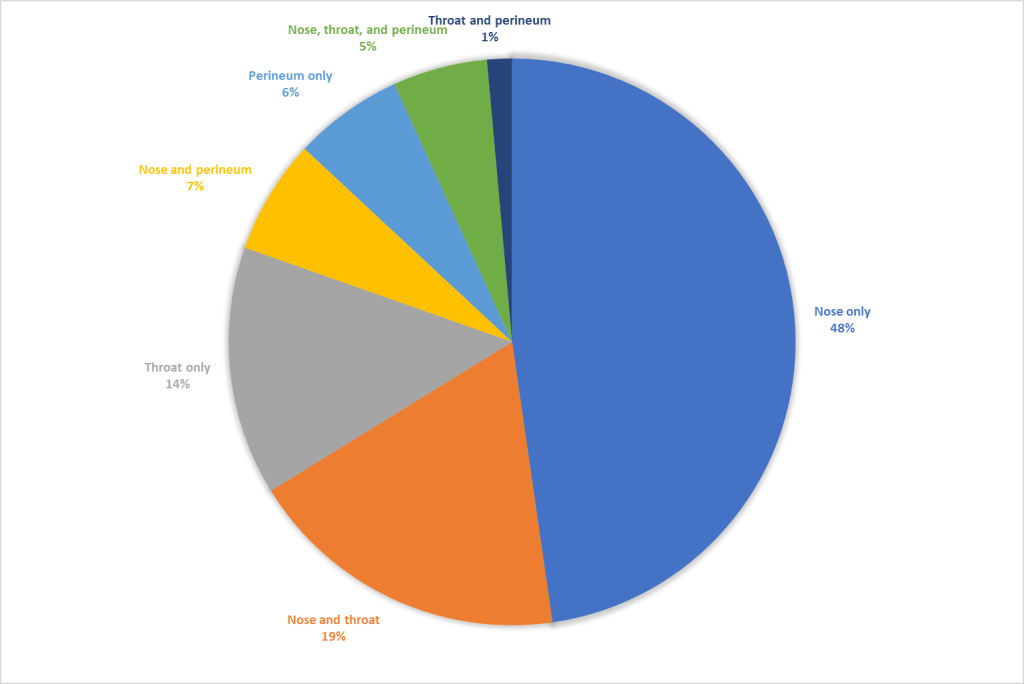

- The S. aureus colonisation rate by site for colonised patients is shown in Figure 1 below.

- A total of 100 S. aureus SSIs or BSIs occurred during the study, 86 of which were in colonisated patients.

- Both S. aureus carriage at any site (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR, 4.6; 95% confidence interval, CI, 2.1–10.0) and nasal carriage (aHR, 4.2, 95% CI, 2.0–8.6) were independently associated with S. aureus SSI or BSI.

- By contrast, extra-nasal carriage was not associated with S. aureus SSI or BSI. However, the risk of S. aureus SSI or BSI did increase as the number of body sites colonised increased.

- There was an association between the bacterial load in the nose (measured semi-quantitatively in the lab) and the risk of S. aureus SSI or BSI.

- There was a relationship between the nasal bacterial load and the number of body sites colonised – the higher the bacterial load in the nose, the more body sites were colonised.

Figure 1: S. aureus colonisation rate by site

Strengths and limitations:

- The study is based on a gargantuan data set, including >5,000 patients from 33 hospitals in 10 European countries.

- Data was collected between 2016 and 2019, so it’s already >5 years old.

- Patients who were colonised with S. auerus were more likely to have received pre-operative decolonisation; despite this, the association with increased risk of S. aureus SSI or BSI remained.

- The study inclusion criteria focussed on ‘clean’ and elective procedures – we know that a large chunk of surgery doesn’t meet these categories and has an even higher rate of SSI, so would have been interesting to see whether the associations remained in a wider group of surgical procedures.

- The bacterial load was assessed semi-quantitatively in the lab. Having done this procedure myself during my PhD, I know that there’s an element of subjectivity about the method, which may have influenced outcomes slightly.

- Also from a laboratory viewpoint, not requiring lab tests to confirm S. aureus (beyond colony morphology) means that S. aureus prevalence was almost certainly overcalled.

- Patients were followed up for 90 days after surgery, so it’s possible that some of the BSIs captured were related to some other cause.

Points for discussion:

- Extra-nasal carriage was not associated with S. aureus SSI or BSI. Does this mean we only focus on nasal S. aureus carriage as a risk factor for SSI?

- There was an association between bacterial load in the nose and the risk of SSI. Should we be targeting patients with a higher bacterial load for specific interventions?

- Most centres do not screen patients for S. aureus prior to surgery. Why is this? And should we consider it?

- What implications does this have for decolonisation / suppression strategies prior to surgery (such as mupirocin, chlorhexidine, or other approaches such as nasal photodisinfection)?

What this means for IPC:

- All roads point to nasal colonisation with S. aureus as the key driver for the risk of S. aureus SSI or BSI.

- Is it time to consider a “screen and treat” approach to prevent S. aureus SSI or BSI, at least in some surgical categories.

- We need to look carefully at our S. aureus decolonisation approach

Finally, hope you can join us for Journal Club next Wednesday (register here).

Discover more from Reflections on Infection Prevention and Control

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.