We know that respiratory viruses can be spread through droplets, occasionally aerosols, and contact routes (see Figure 1). But what is the relative importance of these transmission routes for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19? A new pre-print paper published yesterday provides evidence that the stability of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is broadly comparable to the ‘original’ SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) on dry surfaces and in aerosols. This paper supports an important role for dry surface contamination and aerosols in the spread of SARS-CoV-2, and suggests that improved environmental persistence isn’t the key to the relative success of SARS-CoV-2 over SARS-CoV-1.

Figure 1: Transmission routes of respiratory viruses (from this review article).

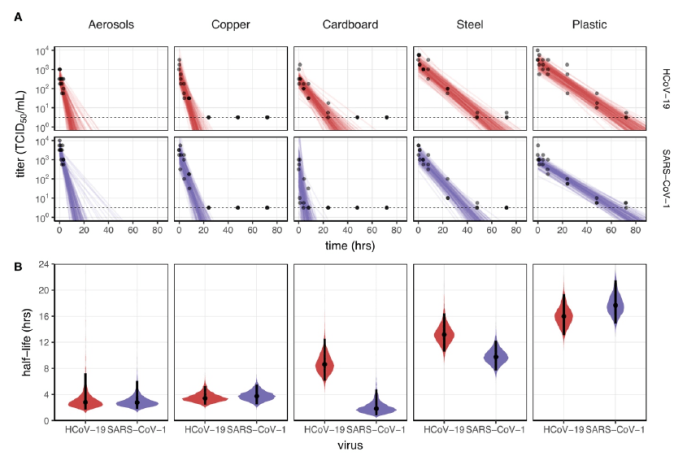

The study team tested the ability of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) and the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus (which causes COVID-19) to survive on a range of dry surfaces (copper, steel, plastic, and cardboard) and in aerosols generated in a drum. Virus survival was broadly comparable between SARS-CoV-1 and -2, with both viruses surviving considerably longer on steel and plastic surfaces than on copper, cardboard, or in aerosols (Figure 2). The half-life of SARS-CoV-2 on plastic was notably high, at around 16 or 17 hours. Even on copper, cardboard, and in aerosols, survival was measured in hours not minutes, and therefore could contribute to transmission.

Figure 2: Measured and modelled decay rates (A) and half lives (B) of SARS-CoV-1 and HCoV-19 (=SARS-CoV-2) in aerosols and on surfaces. Since the SARS-CoV-1 and -2 viruses are so similar, structurally speaking, it’s no surprise that they exhibit similar traits in terms of environmental persistence. However, it is important to note that both SARS-CoV-1 and -2 (and indeed the MERS coronavirus) have unusual environmental persistence characteristics compared with other enveloped viruses.

Since the SARS-CoV-1 and -2 viruses are so similar, structurally speaking, it’s no surprise that they exhibit similar traits in terms of environmental persistence. However, it is important to note that both SARS-CoV-1 and -2 (and indeed the MERS coronavirus) have unusual environmental persistence characteristics compared with other enveloped viruses.

In 2016, I published a review of the evidence on the role of surface contamination in the spread of SARS, MERS, and influenza viruses. This seems to be made relevant again by the laboratory findings of this study. The key findings of the (now out of date!) review were that SARS and MERS coronaviruses can be shed into the environment, be transferred from contaminated surfaces to hands, and result in self-inoculation events. Mathematical and animal models, and intervention studies suggest that contact transmission may be more important than droplet transmission under some circumstances.

Whilst these principles are likely to be applicable to SARS-CoV-2, we have very limited evidence on the role of surface contamination in the spread of this virus. There was much discussion about widespread environmental contamination of the food market where COVID-19 was thought to have originated. This recently published article references this widespread contamination of the food market, but I can’t find the details of this published (like which surfaces were sampled, which method was used etc). And I haven’t seen much evidence (so far) of environmental contamination during investigations of COVID-19 clusters. However, I did come across this study, also on a pre-print server, which tested environmental and air contamination with SARS-CoV-2 in an infectious diseases unit of a Chinese hospital that was caring for patients with COVID-19. The rate of contamination of surfaces and air with SARS-CoV-2 was low: 1 (0.8%) of 130 surfaces and 1 (3.6%) of air samples, and the virus was detected through PCR so no guarantees about viability. However, the positive environmental sample was collected from a shared nursing station, illustrating the potential risk for transmission.

In the round, this evidence suggests that contamination of surfaces and aerosols are likely to play a role in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, national guidelines in the UK around using a disinfectant for environmental disinfection (not necessarily a sporicidal agent) and an FFP3 respiratory for aerosol generating procedures are spot on. However, the relative importance of droplet, aerosol, and contact spread for SARS-CoV-2 is unclear and likely to depend on the circumstances.

Thanks for the write-up Jon. I saw this when it first came out yesterday…I like your Figure 1 drawing as it depicts the various routes of transmission. The transission from droplet to droplet nuclei is what I feel is not well articulated in discussions about transmission of this disease as well as others like measles, rubella, smallpox, chickenpox, and mumps ( and Yes I have been reviewing CDC web sites where droplet, person to person, respiratory spread terms are used interchangeable – except for smallpox…face to face contact).

There are many variabilities to transitioning from droplets to droplet nuclei…I think this organism is findings its place somewhere in the middle….It will be interesting to see the RO will be for this disease.

LikeLike

Dear Jon,

Your reflections and litterature updates are most appreciated for a busy IPC doctor like me, who have so little time to catch up, at the most read the abstracts in these busy times. Please keep reflecting!

In Sweden, in my county and in my hospital I try to keep my own and everybody else’s heads cool. By relying with standard precautions.

Could you please provide me with the evidence as of why on earth do we have to wear gloves when caring for covid-19 patients when no body fluids are present?

When just touching the patient and his/her intact skin?

I find that recommendation in the UK guideline as well as in the Swedish guideline.

This is contrary to all the work we do, to make HCW remove gloves and rely on disinfecting hands instead.

Why is wearing gloves more safe that disinfectiong the hands when this virus is killed instantly by alcohol?

Could you please reflect on this issue?

Many thanks,

Your follower,

Birgitta Lytsy, M.D., Ph.D

Medical specialist in infection prevention and control

Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infection Control

Uppsala University Hospital

Dag Hammarskjolds vag 38

SE-75185 Uppsala

LikeLike

Hi Birgitta thanks for your thoughtful comments. Whilst there’s some logic in NOT wearing gloves for COVID+ patients (because of all the risks associated with inappropriate glove use). current PHE guidelines recommend this, and in the UK, we in the UK should follow those.

LikeLike

A vital piece of information for formulating strategy to curb the spread of this SARS virus within our communities and environment. It is possible that the virus will circulate back to its original host which is bats, via the environment, then mutate again. Unless all transmission paths from the host to human are disrupted, the mutated virus will come back and infect human beings again. Sound horrible as if this is a science friction but this scenario does exist.

LikeLike