We know that many vegetive bacteria can survive on dry surfaces for longer than you might think. For some Enterococcus species, this capability is nothing short of extraordinary. In one study, Enterococcus dried onto a surface was still viable 4 years (yes FOUR YEARS) later! How can this be? No nutrients, no water (other than ambient humidity), and not an endospore former. A recent paper in the JHI may have some answers: Enterococcus is able to form dry surface biofilms and these contain viable Enterococcus many months after inoculation, regardless of species and substrate.

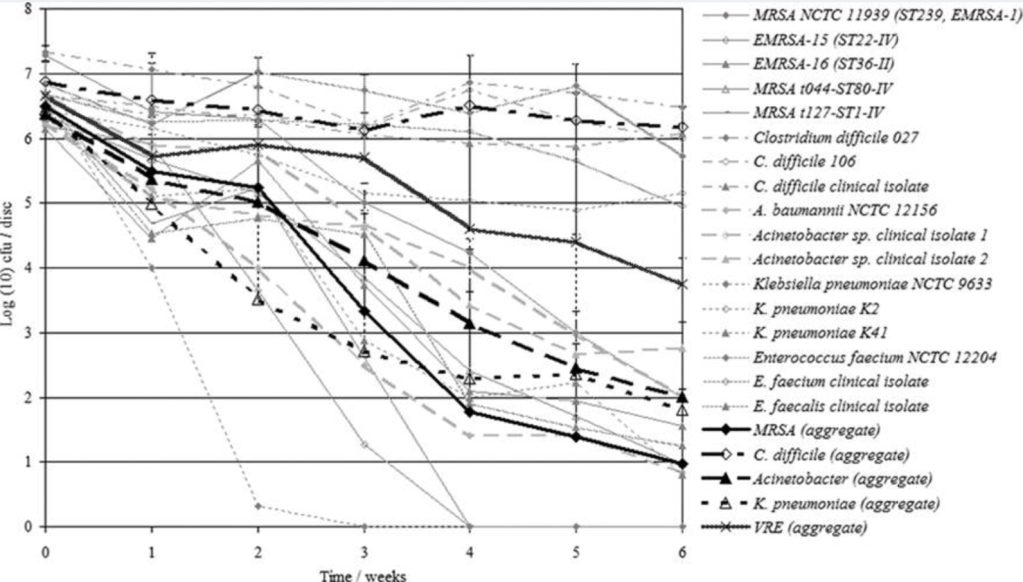

In preparation for my lecture at FIS tomorrow, I’ve been looking at some of my older research papers. This one struck me, where I dried down a range of vegetative bacteria and C. difficile spores onto metal surfaces and assessed their viability over time (see Figure). As you can see, VRE was king of the vegetative bacteria, not far behind C. difficile spores in terms of surface survival.

Figure: Viability of bacteria and spores dried onto metal discs over time (from Otter et al. J Clin Micro 2008).

Background

While hydrated biofilms have long been recognised as reservoirs for pathogens, recent research highlights the role of dry surface biofilms (DSBs) in sustaining microbial persistence on hospital surfaces. This study by Harsent et al. provides some answers about the ability of Enterococcus species to form DSBs and their implications for infection control.

DSBs are thin, heterogeneous microbial communities that form on surfaces subjected to alternating wet and dry phases. Unlike hydrated biofilms, DSBs exhibit:

- Enhanced resistance to disinfectants and physical cleaning.

- Long-term survival, even under desiccation stress.

- Ease of transfer, increasing the risk of cross-contamination.

Previous studies have documented DSB formation by pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae, but the ability of Enterococcus spp. to form DSBs had not been systematically explored.

Study overview

The research evaluated:

- Species and strains: Multiple Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, and E. hirae isolates, including epidemic and VRE strains.

- Surfaces: Stainless steel, PVC, ceramic, and textiles commonly found in healthcare settings.

- Methods: A standardised wet/dry cycle model for DSB formation, culturability assays, and structural analysis using SEM, confocal microscopy, and flow cytometry.

Key findings

- Universal DSB formation. All tested Enterococcus strains formed DSBs on stainless steel and other healthcare-relevant materials, including fabrics.

- Persistence over time. DSBs maintained high culturability (5–6 log₁₀ CFU/mm²) for up to 84 weeks at 20 °C and 55% relative humidity. Epidemic strains and VRE isolates survived for nearly two years.

- Surface characteristics. Surprisingly, surface roughness and hydrophobicity did not correlate with DSB formation or bacterial recovery, challenging assumptions based on hydrated biofilm behaviour.

- Viability and resistance. Confocal imaging and flow cytometry confirmed live cells within DSBs. VRE strains exhibited lower culturability than non-VRE strains but retained vancomycin resistance, suggesting a metabolic trade-off.

- Structural heterogeneity. SEM revealed uneven coverage and variable EPS density across surfaces, mirroring observations in clinical environments.

Implications for IPC

The ability of Enterococcus spp. to persist in DSBs for extended periods underscores the limitations of current cleaning protocols. Key takeaways:

- Routine disinfection may fail to eradicate DSBs, even on “clean” surfaces.

- Mechanical removal combined with effective disinfectants remains the most reliable approach for hard surfaces.

- For textiles, discarding contaminated items may be necessary until validated decontamination methods (e.g., steaming) are established.

- Improved detection methods are urgently needed, as standard swabbing recovers only a fraction of DSBs.

This study shows that if we don’t proactively remove Enterococcus from hospital surfaces, natural loss of viability over time won’t enough to be useful for applied IPC purposes. Addressing this challenge will require innovation in cleaning technologies, detection methods, and further understanding of biofilm biology in healthcare environments.

Discover more from Reflections on Infection Prevention and Control

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.