I did a talk at the Infection Prevention 2024 conference in Birmingham earlier in the week on ‘making peripheral vascular access a central focus’. Understandably for many reasons, much of our vascular access infection prevention effort is focussed on central lines. But this means we probably don’t spend enough time considering infection (and other complication) risks from peripheral vascular access and what we can do to prevent these.

You can download my slides here.

Vascular access is a critical and almost universal part of modern healthcare. If we get vascular access wrong, patients have a bad experience (and many single out vascular access issues as the biggest issue of their hospital stay), treatment delays, unnecessary resource utilisation, clinical complications including line-related infections, litigation, and sharps injuries for staff. Around 30-50% of inpatients will have a peripheral vascular catheter (PVC) at any one point in time, and 70% will need a PVC during an inpatient stay. Shockingly, around 50% of PVCs will fail (for one reason or another, be it occlusion, infiltration, phlebitis, or infection). Evidence suggests that PVC-BSIs account for more than 20% of catheter-related BSIs, but there is a surveillance gap here in detecting PVC-BSIs. When PVC-associated BSIs do occur, they are just as impactful as central venous catheter CVC-BSI, with similar mortality rates.

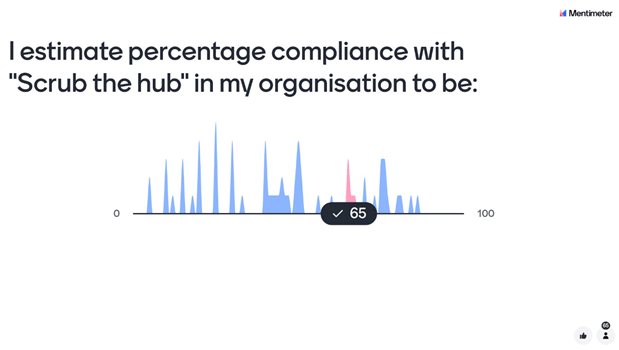

Most guidelines recommend clinically indicated replacement of PVCs as opposed to routine replacement. There is evidence that clinically indicated replacement can result in an increase in rates of complications if PVCs are not cared for when they’re in! So, I’m all for clinically indicated replacement, provided we have assurance that PVCs are being cared for. When we look at compliance with “scrubbing the hub”, compliance is very often, shall we say, sub-optimal (both in terms of doing it at all or doing it for long enough). So, we have work to do in making improvements in compliance of scrubbing the hub, and looking at other options (such as passive disinfection). The image below is a mentimeter poll that I ran during the talk, illustrating a wide range in estimated compliance with “Scrub the hub”:

There is lots we can do to reduce the risks of complications from PVCs when managing the care of individual patients. We can also do system-wide improvements in PVC practice, perhaps best summarised as “put fewer in, take better care, and take them out sooner”. If we get this right, we will improve patient safety, save money, and contribute to more sustainable healthcare.

Finally, there will be an IPC Journal Club Special tomorrow, with Dr Mark Garvey, Dr Jude Robinson, Dr Phil Norville, and me bringing you some highlights from the Infection Prevention 2024 conference (register here).

Discover more from Reflections on Infection Prevention and Control

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Dear John.

Still the policy of the university hospital: keep it as long as it lasts without pain, or erythema.

I did a RCT with 1800 peripheral catheter (unpublished) and the main result was, that the complications are the some per day . however, if you compare risk during the first 3 days vs more than 3 days (D:Maki’s Studies), there is a difference.

Our Swiss representative Dr. Buetti N has recently published on the topic, but the main problem remains that the peripheral catheter does not get proper care, and this case, scheduled replacement forces the nurses to take care of it.

Problem over the last 40 years, still unresolved.

Best regards

andreas

LikeLike